Creative Phase Two: Spring 2007 (three weeks – part-time)

In the second creative phase we reconstructed iconic Hollywood duets including Rudolf Valentino's infamous tango from the 1921 silent film The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, sections of Astaire's duet with Cyd Charisse in The Band Wagon (1951), and Gene Kelly's first duet with Leslie Caron in An American in Paris (1951). Not surprisingly, these duets emphasized a heterosexual relationship that focussed on the woman's dancing, her elaborate costumes and the sexualizing of her body. In the end, however, we discarded these duets as we were interested in expressions of masculinity, not heterosexuality. In the same process period, we also explored unison duets performed by Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly in Anchors Aweigh (1945) and Gregory Hines and Mikhail Baryshnikov in White Nights (1985). These unison male duets suggested “traces” of the African footwork that is an essential aspect of Hollywood choreography, and the elaborate Baroque dance patterns that Louise XIV used to express harmony on earth. Also, we began the process of creating an abstract, gestural sign language for an abbreviated version of the monologue “Jerry and the Dog” from The Zoo Story.

Dancers: Louis Laberge-Côté, Shawn Newman, Jessica Runge

Generously supported by the Ontario Arts Council

Creative Phase Three: Spring 2008 (three weeks)

Working with four dancers, we solidified the gestural sign language for our abbreviated interpretation of the “Jerry and the Dog” monologue from The Zoo Story. When this was completed, the dancers selected sentences that resonated with them and created full-body dance phrases that interpreted the essences of the words and gestures we referenced from the monologue. Once this was complete, the dancers placed a second meaning on top of their full-body phrases from such films as Cool Hand Luke (“What we have here is a failure to communicate.”) and It's a Wonderful Life (“You know how long it takes a working man to save five thousand dollars?). In this way the dancers were able to physically explore aspects of the effects that happen when signifiers change their meanings or when signifiers evolve to include other meanings. In simple terms, the theoretical argument for this investigation is that “traces” of past meanings will remain, sometimes invisible, as the primary signifier (gesture) evolves to produce new meanings or interpretations; and it is this process of identifying and interpreting meanings that produces the gendered codes or signifiers we assume as obvious. Once the entire monologue had been physicalized and layered with a second meaning, we edited the phrases together to reference the six musical sections from Gene Kelly's signature ballet in An American in Paris (1951). Working with Kelly's vision of one man's romance with the city of Paris, the famous painters who interpreted Parisian landmarks, and the woman he loves, we added a third layer of potential meaning to our choreographic language.

Dancers: Johanna Bergfelt, Louis Laberge-Côté, Shawn Newman, Jessica Runge

Generously supported by Canada Council for the Arts, SSHRC Research/Creation and the Faculty of Fine Arts at York University

Creative Phase Four: Summer 2008 (two months)

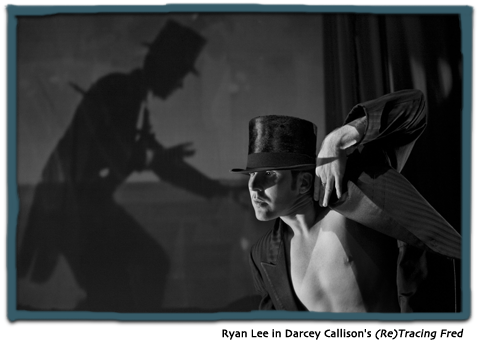

Canadian scholar Marshall McLuhan observed that the cinematic image appears more real or immediately compelling than the actual lives of the people sitting watching the film. McLuhan made this observation in the early 1960s, long before today's audiences had developed the sophistication to interpret complex cinematic images. In contrast, Astaire established his film identity when Vaudeville was still popular, and when audiences knew and understood the presence of live, theatrical performances. The challenge we faced in this creative phase was to balance our sophisticated familiarity of projected images with the present, personal bodies of live, theatrical dancers. Collaborating with media designer Simon Clemo, film director Ines Buchli and lighting designer Elizabeth Asselstine, we explored relationships between live dancers on stage and their projected image on a screen. Our goal was to create a balanced relationship that allowed the live dancers to assert their presence with the same sophistication and impact as the projected images.

Dancers: Johanna Bergfelt, Louis Laberge-Côté, Shawn Newman, Jessica Runge

Generously supported by Canada Council for the Arts, SSHRC Research/Creation and the Faculty of Fine Arts at York University

Creative Phase Five: January and February 2009

I have no desire to prove anything by dancing. I have never used it as an outlet or a means of expressing myself. I just dance. I just put my feet in the air and move them around.

– Fred Astaire

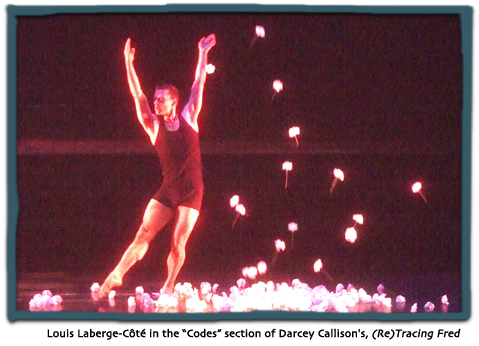

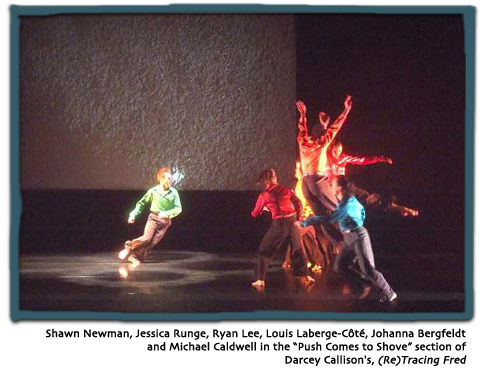

We could continue exploring forever; there is no end of possibilities and no finite statement to be made. At some point you bring your creative explorations to the stage and trust that the work will speak for itself. Theatre maverick Ann Bogart writes, “The real event [of theatre] is an encounter, a meeting, and engagement, a summit, a collision, a collusion, a collaboration, or congress of souls. The event [performance] is a meeting between actor [dancer] and audience and it is this encounter that forms the nucleus of the theatre experience.” (Re)Tracing Fred is our encounter with audiences, our collusion with the movement languages that justify many boys' desire to dance; our collaboration with the visible and invisible codes that identify the “man” dancing; and our embodied encounter with a movement vocabulary that we have learned to love and respect.

Dancers: Johanna Bergfelt, Michael Caldwell, Louis Laberge-Côté, Jennifer Dahl, Ryan Lee, Shawn Newman, Jessica Runge

Generously supported by The Toronto Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts, SSHRC and the Faculty of Fine Arts at York University

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni