Fred Astaire, Elvis and Louis XIV – Tracing Masculinity in (Re)Tracing Fred

Fred Astaire, Elvis and Louis XIV – Tracing Masculinity in (Re)Tracing Fred

A faculty member of the Department of Dance at York University, Dr. Darcey Callison is a choreographer, teacher and dance scholar who has worked extensively with Authentic Movement, the Physical Voice, Viewpoints, and post-modern theatrical dance. The founding director of York's MFA in Contemporary Choreography and Dance Dramaturgy, his creative research has recently focussed on dance as a site for constructing gendered and cultural identities.

Darcey Callison gave his Choreographic Dialogues presentation on February 14, 2009. His work (Re)Tracing Fred was performed at the Sandra Faire and Ivan Fecan Theatre at York University from February 24-28, 2009.

Unfortunately, Dr. Callison's presentation was interrupted by a fire drill. Resolving the drill consumed most of the presentation time, and there was no remaining time for questions from the audience. So, while this particular Choreographic Dialogue differs from the others (as there are no questions), it reproduces his thorough and thoughtful program notes, which set out his creative/investigative premise and detail the process of making (Re)Tracing Fred. His notes put forward a dramaturgical perspective on choreography and track the multiple stages of researching the choreography; and his approach to identifying and considering the many sources and influences within (Re)Tracing Fred offers a unique perspective on artistic research in an academic milieu.

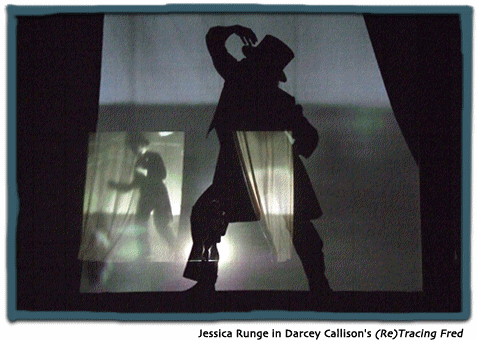

(Re)Tracing Fred was produced by Da Collision, Darcey Callison's company, and performed by interpreters Johanna Bergfelt, Michael Caldwell, Jennifer Dahl, Louis Laberge-Côté, Ryan Lee, Shawn Newman and Jessica Runge, all of whom Callison also credits as “co-choreographers” of the work.

Program Notes – (Re)Tracing Fred

The impetus for (Re)Tracing Fred began many years ago when I was a young boy participating in dance classes and my teacher re-named me her studio's “Fred Astaire”. In retrospect I believe she re-named me to justify my participation in what is generally understood in North America as an activity for girls or sissies. After many years working professionally as a choreographer, I realize that my re-naming was not a unique experience and that many boys are re-named in dance classes throughout North America in order to reference “traces” of the danced masculinities understood and accepted by North American audiences. Today, the vast majority of the danced masculinities being “traced” in order to justify men and boys' desire to dance, is derived from Hollywood's first and arguably most popular male dancer – Fred Astaire.

When investigating Astaire's dancing career, it became clear that the movement vocabulary he popularized could be “traced” to the Plantation Dances invented by African slaves as parodies of European social dances. These parodies evolved into the Minstrel dances that were popular on the Vaudeville circuit at the turn of the century when Astaire first danced as a member of his theatrical family's business. Other aspects of Astaire's vocabulary and persona can be “traced” to the Baroque dance vernacular of Louis XIV who danced a decorative masculinity as political performance, in order to establish his patriarchal/divine right to rule. However, Plantation, Minstrel and Baroque dances are only three reference points of what is an intricate, web-like network of historical, cultural, political, gendered, personal and institutional dance “traces” embodied by Astaire as Hollywood's first white male dance celebrity. An important aspect of this network of dance references includes Astaire dancing in the same Hollywood studio-era as influential African American dancers such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and The Nicholas Brothers. Although it is difficult to know what immediate influences these African American dancers had on Astaire's choreography, we do know that “Bojangles”, the Nicholas Brothers and Astaire all danced on Vaudeville and that borrowing steps and competing with other dancers was a regular practice within Vaudeville's dance culture. Interestingly, Robinson, the Nicholas Brothers and Astaire wore versions of the traditional Minstrel tuxedo as part of their stage and screen personas as a means of referencing the “traces” of their dancing to the European social dance parodies mentioned above. However, in the racist setting of studio-era Hollywood, it was Astaire who made wearing a tuxedo a symbol of white, upper class mobility and who became North America's iconic male dance star and the primary signifier for all other Hollywood male dancers to “trace”.

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni