I chose two different excerpts to show to you. I selected these because I'm working on these two pieces right now. One is called La Chambre Blanche. It's a piece that I created in 1992. We started the research for that piece in 1989 and at the time in Montreal a sad event happened. A man killed fourteen women at the Polytechnique, and we were very touched and sad about that. It really influenced us in the research. I wanted to work on the thin line between being in control and losing control. We did the piece and it worked really well. I think it was the piece that made the reputation of the company. We toured it everywhere, and it would touch people in different ways. It's very theatrical.

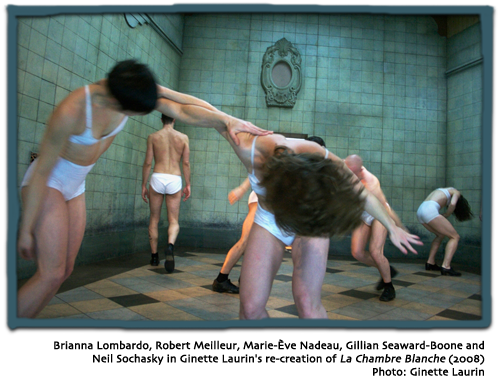

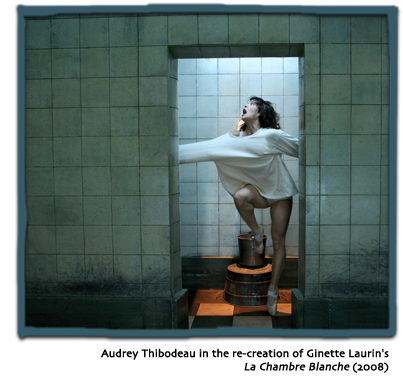

I decided to use a set that would evoke a mental hospital. The set is a room that in fact we copied from a hospital in Montreal. It's an old building and we set windows really high so the people can't see outside. It's close to theatre, because we have characters and they have costumes like actors would have, but it's mainly movement. They speak a lot, but for me it's not important that we hear what they say. The dancers had to work hard trying to find this flow through the words. For me, it makes the dancer more true – if you add another level, another difficulty along with the dancing, they become much more real and true and fragile in a way. I wanted to have that kind of fragility and it worked really well.

I first did the piece in 1992, and then decided sixteen years later to do it again. I watched the video and thought, “No. I can't just remount it as it was.” I had to change the music and I changed some sections. I had to re-actualize the piece. It was important for me to keep the same intention. In fact I decided to do it again for the stage – I had an offer to make a film about the piece, and we thought since we were doing it for the film we should prepare it again for the stage.

We've been presenting La Chambre Blanche for about a year now. What you will see is the film. I won't show the whole thing because it lasts forty-five minutes.

As you can see, it puts the dancer in a very specific situation. The space can refer to a mental hospital, to a common bath, shower room, or something like that. The grilles, for me, were used as a confessional. So elements mix, and are suggestive of religion, mental disorders, water, purification. All these things were mixed to explore the thin line between balance and going off balance. I play with this, with the dance, using pointe shoes and also with the planks around the walls that are wide enough so the dancers can step on them but not wide enough to stay on. Those elements were used to create the choreography and to express the theme I wanted to explore.

We worked with improvisation and through workshops; we worked with trying to identify which character each dancer could be. For example, how old they are, why are they in this mental hospital and perhaps what kind of medication they take, in order to give them a framework to work with. Of course I didn't want it to stay in their heads, I wanted them to bring it into their movement. There was a phase where we had to stop trying to intellectualize and try to express with the dance. I wanted to structure the piece using a lot of chaos; I didn't want it to look like everything was choreographed, although it is. The last section looks very explosive and improvised, but it's all set. They are always using their voices but, because they are all talking, we don't necessarily hear what they say. For me it was more a question of adding to the chaos, adding to the delirium.

The costumes in this later version are the original costumes. It's funny because the dancers are different but the costumes are the same. I didn't want it seen as if it was happening in a specific time, I wanted the piece to be timeless. So we decided to go with that kind of architecture for the set and costumes. I decided to use underwear, because again it puts the dancer in a more fragile situation. I didn't want to use complete nudity because I think they look even more fragile in that ugly underwear! And to me it relates to this place where they wash and purify; I wanted to have a contrast between the white and the black.

For me it's not important that people understand exactly what is happening. I think in fact I can relate it to literature. It's more as if you were reading a book of poems and it speaks to you as you want it to speak to you. Of course I want people to be moved, but I prefer if they don't think they have to understand everything. That is the big problem with dance. It's funny because with visual art people don't try to understand everything. I always tell people, well, all the notes in music, all the colours in paintings don't mean something specific, so you have to try to read dance the same way. Let the dance touch you and take it with your heart, with your belly, more than with your head.

CA: I have a question about La Chambre Blanche. I heard that when you remounted it the women shaved their heads. Is that so?

GL: We had the same for the first version. We had three women shaving their heads. When they go through a process they really dive deeply into it – the dancers suggested it to me. When we went to Israel with the piece, people saw the gas chamber, especially with those heads, and they were very touched by that.

The music is now completely different, and the music from the film is different from the music for the stage. I kept only two sections with the exact same movements as the original. And some of the sections are the same, except I didn't want to use the video documentation to reconstruct it; I didn't want the dancers to copy. So I explained what the sections meant and re-choreographed it using the same energy, the same content.

Q: The walls are such an element in the movie version. Did you have walls in the stage version?

Q: The walls are such an element in the movie version. Did you have walls in the stage version?

GL: Yes. In the movie we have six walls so it's completely closed and we have the camera inside the space. For the stage we have three walls, plus the ceiling, and this little room at the back. So it's quite something to tour, but it's all made with pieces of 4x8 and the structure is aluminium. It's the same set as before. In June we go to Europe for the fifth time this year – we left the set there, so we saved money (laughs).

Q: How did you get the dancers to really understand, both bodily and intellectually, what mental states people in such institutions could experience, and how they show certain signs of being somewhat unbalanced?

GL: Having the set at the beginning of the improvisation process helped a lot. I love that set. You go inside and you instantly feel where you are. I asked the dancers to observe as they take the bus, the subway, as they cross the street, if they could see people who maybe had just a tic. We started improvising with those repetitive movements. If you do it long enough, it brings something out. We try to bring confidence into the group so they will be able to let this out. But it took a while.

Q: It's interesting how it went from the shoes to the pointe shoes, how it changed the aesthetic of the body. Did you have a particular point in changing, was there an aim?

GL: The pointe shoes were quite special in 1992! Now, all the modern companies use pointe shoes, but at that time it was unusual. For me it was the idea of having something that makes the dancers, again, very fragile, and a place where they can fall off.

Q: So did they start more grounded which is why they were wearing shoes?

GL: We have black shoes at the beginning, and in the middle we have a long part with the pointe shoes. All the women wear pointe shoes, and by the end they have their black shoes on again. Each tableau talks about the same thing in different ways, and one or two of the tableaux contain this exploration with balance.

GL: There's a really beautiful relationship between the men and the women. It's not na´ve but very simple. There's one section where they're throwing each other around and then playing with the skirt, but actually quite a change from the beginning where there was that kind of abrasive seal that he was putting around that girl with the long hair. Did you develop a stream of relationships throughout the whole piece because it was built into the space?

GL: The nine dancers are in that space almost all the time for an hour, so of course they meet each other. Some relationships appeared naturally and we used them. I found out that if I wanted to explore a theme that was so dark, at some points, they had to have places for escaping, through their imaginations perhaps … you had to let go of the pressure. And this last part is one of the sections where it just explodes and many different relationships appear through that delirium. We had a period of watching films, for example One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and other films. There's always a party with the crazy people at one point in the film. So this is our crazy party! (laughs)

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni