Q: Each of your works is such a distinctive world unto itself and I think of how Chagall looked, or La Chambre Blanche, or Train d'Enfer, or Luna. Each one of your works is such a distinctive universe. I wonder if you could talk to us about your creative process and how you come to create those distinctive worlds.

GL: I think that it happened for a very simple reason. I was working with the same dancers and they would stay. For example, Ken stayed with us for twenty years, Anne stayed with us for fifteen years; so I wanted to make sure when we went back to the studio for a new creation it wouldn't be boring for anyone (laughter). So that, I think, is the main reason. For me it's important to find a process so each work would be different. But also working with different collaborators for the set, the music and lighting would help. But yes, it comes from the process; we would research for each piece.

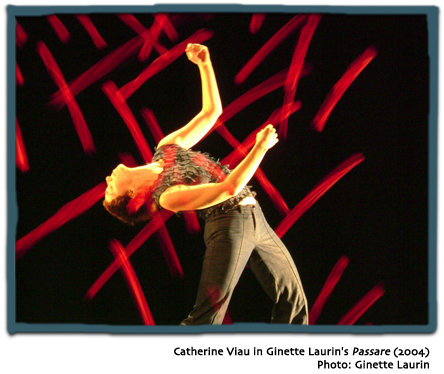

Ginette Laurin's Luna (2001)

Q: You have done very different kinds of research for your pieces – is that also to keep you all stimulated or following particular ideas that you have had?

GL: Yes. The last pieces were made from an exploration I did with an astro-physicist. I worked with him for about four years and we made two pieces, Luna and Passare. And for the next piece I would like to work with a cardiologist because I want to work around the vital energy and the heart with all that it evokes, but I want to have a medical aspect and a mechanical body concept. I want to explore that. It's fun – I'm curious and I like the link between art and science. I think that people from science are very creative and sometimes confirm the intuition that artists can have. It's nice having a dialogue with scientists.

Q: Would that be why you want to have the sets from the beginning – in order to create the atmosphere of this new place where you are taking your dancers?

GL: Yes. Before I start working with the dancers in the studio, I know what my set will be. I have the set and I know what the music will be or what kind of atmosphere. I know everything. For me it's very important.

Q: The colours that you use are also very vivid. I'm also a dancer/visual artist and I really appreciate when a piece has that visual strength. Is that something that comes innately to you, or do you collaborate with visual artists?

GL: For this piece I didn't work with a visual artist. I worked in collaboration with a lighting designer. We wanted to play with reflection and transparency, and with having the musicians visible sometimes, and not visible at others. Also the floor. I like to work with a certain design on the floor, because I'm tired of Marley floors. So if I have a chance, I try to have something different. Again, it helps how the lighting works. And yes, the visual aspects for me are important, are part of the dance.

Q: I'm curious about the music. Is touring arranged by musical ensembles who wish to perform it and they invite you, or do your presenter networks arrange performances?

GL: It's the presenter who will set up the ensemble and find the conductor who will be willing to do it that way.

Q: And does the musical ensemble pay the musical costs?

GL: Yes. And we go to the city one week ahead to rehearse with the musicians.

Q: I'm quite curious about the presenters you work with and about your rhythm of work and touring – how is that organized, and how does that affect your creative work?

GL: La Vie qui bat we won't tour a lot. We will do a few big cities and that's all because it's very expensive. They have to pay twelve musicians and all our team, which is seventeen people, a week ahead of the show, so we do it mainly for festivals and things like that. We have an agent in Europe and our manager is good at finding the right presenters for us and making contacts. But I guess it's also because we've been touring for twenty-five years, so I think we're better known in Europe than we are in many parts of Canada.

Q: The imagery that you use on the stage, like the confessional in La Chambre Blanche, is that something that you witnessed growing up? Or is that something that you have seen as you have travelled?

GL: I think work can be true only if you use who you are, and your roots, and what you believe in or your preoccupations. It has to come from you. This is the main rule, I think. So La Chambre Blanche – yes, it contained a lot of memories from my childhood, the Catholic religion, the events at Polytechnique, things like that.

Q: Whereas the second piece is much more transparent.

GL: It's formal. So it's another style. It's another way. It's just my way to see or understand Steve Reich's music. For me it's about continuity. It's my reading of his music.

Q: There's a lot of talk today about writing and dancing … I just wonder – do you do any writing about the dance?

GL: I should say that I don't believe in writing because I think it can't be precise enough. It takes so long to describe one movement. But very often I ask the dancers to write, to remember. There's a lot of movement and it's a long process so I ask them to write where a movement happens and what's their cue to enter …

Q: I don't necessarily mean recording what you are doing. I'm just wondering, because some choreographers use writing. The dancers write as part of their creative process; or maybe it would be more closely related to La Chambre Blanche when the dancers play characters.

GL: They do have to write. As I said, I asked, who are your parents, who is your character, who are you? I gave them a sheet and they fill it out. It was funny. Some of them wrote fifty pages and some others just two pages, but I think it was a process that was very helpful.

Q: Do you ever do that yourself?

GL: For the film, I had to write a script. I had to write about fifty pages telling the story and it was helpful, that's true.

Q: Maybe you have other people do this for you, but do you have to write grants?

GL: I have to write about the next pieces. I have to describe what the next piece is going to be and I have to write about it. It's a normal process. It helps you to organize yourself. What do you want to talk about, and how are you going to do it, and what elements do you want to use and why? I think it's important. You have to articulate for yourself – for the dancers, and to get the money.

Q: You were talking about writing a script.

GL: We had to translate it into English, since Bravo! is the main producer, main funder, but I wrote in French.

Q: French is also very precise.

Q: To an aspiring professional choreographer, is the process of obtaining grants and sustaining a financial living from your work exclusively an intimidating process? And, if so, is there any advice you can provide for people who are aspiring to make this their living?

GL: We are artists, but even in the time of the kings the artists had to sell their art and they had to find a way to survive if that's what you want to do for a living. You have to find a way. So, yes it's not my cup of tea. Of course I much prefer to be in the studio, but I think it's normal. I usually spend half of the day in the office and the other half in the studio.

Q: Do you ever find that the competitive nature of the industry infringes on your creativity, and if so do you have certain coping mechanisms to deal with that?

GL: Sometimes I wish I was a teacher in order to make a living, and created the pieces on the side so I wouldn't have to do that work. But then I think, “No, that's what I want to do.” As I said, I didn't plan to have a company. I started with a company that already existed. But there is much administrative work we have to do.

Q: Do you have different ways of seeing dance for different forms of research? For example, for the Steve Reich, you chose pedestrian movements. Is there a way that you were trying to be more responsive to the audience or is that just something that grew? Was there a way of relating more easily to the audience in relation to that piece?

GL: I don't think of the audience very much. I think that if I do something that speaks to me, or if I have a great desire to express something my job is to express it so clearly that it will get to the audience. But I don't think, “Oh, I have to do something they will like … what's trendy, what's new.” I think it has to come from the inside, and then it must be expressed so well that people will receive something from it.

CA: Thank you so much, Ginette.

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni