DH: Christopher had asked me before to come here and choreograph a piece for the company. So when Christopher was at the Solo Commissioning Project in Findhorn last summer, learning this solo, I said, “Christopher, why don't you take this material and bring it back to the company. You can teach them the sequence of material, you can teach them the questions that are asked while the dancers are practising this dance. So when I get there in January they will already be practising.” I think this is a unique thing that's happening here. I don't know that it's happened anywhere before. When I arrived the dancers already had the movement vocabulary, the movement directions that guided this piece, and all I am essentially doing is guiding them in the performance of it, and rearranging the material a lot. But they are at ease with my language because Christopher has already set it up. They have already learned the movement description that describes the sequence of the material that takes you from the beginning to the end of the dance. It's quite a luxurious situation for me; I don't think I could do it if you just invited me, and the company had no sense of the way in which I work. I'd have to spend three or four months here.

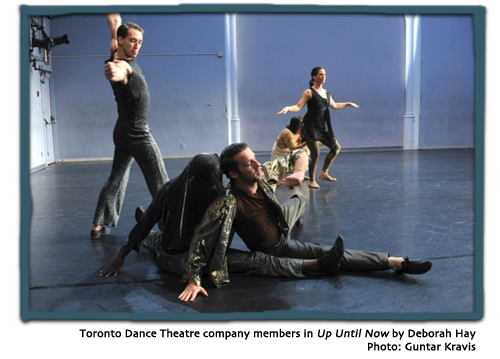

The solo I talked about in the Solo Performance Commissioning Project was called I'll Crane For You and this piece for the wonderful dancers from the Toronto Dance Theatre is called Up Until Now, because it's a dance for eleven dancers and a different configuration than the solo.

CH: I think some people are interested in what happened during the fall. I spent probably 2 and a half weeks at the beginning of the year working with the company learning the score for Up Until Now. And also – and I think this is important – we really worked on the questions surrounding the practice. It wasn't just looking at what you might call the mechanical aspects of the score. Then we started to work on a new dance, which I presented in November, a piece called Dis/(sol/ve)r. The work that we had done with Deborah, in Deborah's absence – and I think the dancers would agree – really informed our process in making the new work. In fact at a certain point we began to do less playing, less research and decided to set things. We decided pretty spontaneously as a group that we wanted to return to a daily practice of Deborah's questions as a way into what we felt were some of the essential aspects of the things we were looking for. Dis/(sol/ve)r is a very different dance for me for a number of reasons. One important thing is that it's a dance about transitions, in large ways and in small ways. One of the things about Deborah's work that I love, that is so beautifully refined in her practice, is the way in which transitions occur without you suddenly saying, “Oh look it's the men's dance,” and “Look, it's the up-tempo section.” I don't see those things happen. I just suddenly notice that I'm in the middle of it. It's one practice. There are no transitions. What are transitions? So we can get rid of that; and I'm still stuck in transitions and that's what I'm working on in my piece. (laughter)

CA: Deborah, you score your dances. Is the score a series of questions?

DH: No, I love to write my dances after they've been performed. As a matter of fact, I choreograph them after they've been performed. Because it's only when I've seen them performed that I can really make good decisions about the choreography. I write my dances after they have been performed to help me choreograph them, so the scores are very different from the performances. I wrote one score in the form of a play for four characters. I wrote another score in the form of a poem. In my book My Body the Buddhist there is a score for the dance Voila that's a long poem.

CH: The first score that I learned, News, describes a number of activities and there's a very specific spatial pattern in this work. I'll Crane For You has some things in common and it's written in the “he's” as opposed to the dancer or you. It's all about “he's” or “she's” and there are absolutely no spatial directions at all – except I feel some things happen on the edge of the space.

CA: So the choreography actually is in questions?

DH: The questions are part of the performance. And the dance couldn't happen without the questions. You need the questions to guide the performer in the enactment of the movement descriptions.

CH: So these mysterious questions are the things you are considering that inform the choices that you're making, and it's an ongoing process. There's a third element. There's the score and the questions and certainly, in the experience of doing the Solo Performance Commission, the third element is that Deborah is very much a choreographer. So, she will say what she likes and doesn't, and she'll make rules based on what she's seeing. She uses that experience, I think it's fair to say, as part of the research for where the dance is going to go; and she's learning from the twenty people who are dancing. The same thing began with the score for Up Until Now. The dancers are very deeply involved in this performance practice with the questions, but you're making decisions all the time both bringing them into the present, and making spontaneous decisions with Rosemary [TDT Rehearsal Director Rosemary James]. And you don't talk about that part. Can I ask you a question, because I'm curious about that process.

DH: Well, I have this thing when coaching dancers, and it's called “Ready, Fire, Aim”. It's very exciting performatively to do “Ready, Fire, Aim” because, as performers, it seems to me if we do “Ready, Aim, Fire” we'd be aiming forever. And so to do “Ready, Fire, Aim” I short circuit my conscious mind and get to notice things that would not happen otherwise. I see these dancers, with these instructions in their “Ready, Fire, Aim” do things that are fantastic, so if I see something I say, “Oh, we have to add that too.” The more liberties they take, the more they are able to play the rules, and the more exciting it is for me as a choreographer. I just want the rules to be broken! But they have to be broken in a way that will throw me. A lot of the things that I see in this “Ready, Fire, Aim” of these individual dancers, I have to see in the performance in order to choreograph. I get to see these moments that I can then add into the vocabulary, the choreography.

DH: Well, I have this thing when coaching dancers, and it's called “Ready, Fire, Aim”. It's very exciting performatively to do “Ready, Fire, Aim” because, as performers, it seems to me if we do “Ready, Aim, Fire” we'd be aiming forever. And so to do “Ready, Fire, Aim” I short circuit my conscious mind and get to notice things that would not happen otherwise. I see these dancers, with these instructions in their “Ready, Fire, Aim” do things that are fantastic, so if I see something I say, “Oh, we have to add that too.” The more liberties they take, the more they are able to play the rules, and the more exciting it is for me as a choreographer. I just want the rules to be broken! But they have to be broken in a way that will throw me. A lot of the things that I see in this “Ready, Fire, Aim” of these individual dancers, I have to see in the performance in order to choreograph. I get to see these moments that I can then add into the vocabulary, the choreography.

CA: Deborah, I want to ask you about your writing. Here we are talking about dancing, which is already challenging to do, but you are also a writer. I'm curious about how that comes through you, and how that experience seems to you – writing dancing, writing about dancing, writing in dancing?

DH: In a way it's so simple. If you get the feeling that you're hearing something really esoteric, let me tell you that it is. And in order to articulate the esoteric experience you'd better write it. You'd better put it in writing because otherwise no one is going to know what the hell we're doing.

At a certain point, students would say to me, “Oh this is fantastic. I went home and I saw my roommates and I tried to tell them, and I just couldn't describe what was going on and it was so good.” And I thought, this does not help me. It is not good for me that you can't describe what is happening to you, and I really took that hard. I thought I'd better write this non-linear experience, put it into language in order to maybe have it survive – I better put my non-linear experience in linear form in order to survive as a dancer working fairly esoterically. Fortunately, I was around in the '60s in New York when Dan Flavin and Donald Judd and Robert Smithson were writing art criticism; they were writing about their art. They were articulating – they provided a frame for the people who were looking at expressionism, and they were providing viewers at that time the language for what it was we were looking at.

Dancers were fairly late to pick up the pen, but I think they have now. Certainly Yvonne [Rainer] did it with her manifesto, but not many of us were writing. I think as dancers it's our survival, and the survival of the body is dependent on articulating it. I wasn't a writer, I just thought if I was going to provide a frame for audiences or students or other dancers, choreographers, dance critics to see my work, I'd better start articulating it. Because I was reading stuff about my work that other people were writing and I couldn't relate to it. Well, Selma Odom has written about my work in such a way that I've learned something. How rare is that, where you learn something about your work through their vision? But it wasn't and still is not that common, even in the best circumstances. I was reading chapters on my work and I thought, “That is not what I'm doing. I'd better write my own work.”

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni