Q: You've mentioned how the community feels about blending contemporary with traditional – just wondering if you could elaborate a little. I think you said there are roles for traditionalists and there are roles for creative artists – it's a great way to look at it.

SS: I think that our community is very open-minded. Maybe because we are situated in Southern Ontario. I would never intentionally put a sacred dance on the stage, or even work with a sacred dance. I know the protocol within my own community – I would get into trouble. There would be some backlash if I did that. It is important to be conscious of what's appropriate to share and what is not.

Some ceremonies on our reserve are restricted, especially medicine ceremonies that involve masks. There are three types of traditional steps, and lots of dances have these three basic steps: the stomp dance; the fishing step in which you make three consecutive beats with your feet in time with the drum; and the shuffle, which is a women's dance. Those three steps take different forms, but they are all social dances. In the past, Six Nations groups have toured, performing social dances – they are meant to be shared.

Another thing about Six Nations is that we have a history of performance; we are a very theatrical culture. I did a paper about it when I was here doing my MA – it was about the history of performance. Characters in the history of our communities have been performers. Some have performed in circus acts. Pauline Johnson was a famous poet and orator, very theatrical in her performances, and then our travelling dancers, and the singing societies tour and sing. Performance is accepted in my community, though not in every community. It is important to know this complexity exists on different reserves.

In Blackfoot territory, I performed part of Kaha:wi, which is a women's dance section. It is very female, very connected to the pelvis, very feminine. We are doing the woman's shuffle and it is about using the hips and being very open. In our community that is fine because it's matriarchal, women have power that in other communities they may not. So here I am doing my really exalted women's dance in Blackfoot territory, and there was a bit of a backlash because of regional differences. “Here is this Mohawk woman, what is she doing? She's rolling on the ground.” But within my community, which is who I answer to, it is fine. The whole purpose of song and dance in our community is celebrating life, and people know my whole intention is to continue this celebratation.

Q: I have a specific question about A Constellation of Bones and how you worked with the poet. Did the images from the poetry come first or did the three of you (with the sound person), work all together?

SS: I met Kateri, the poet, at an event and heard her recite her spoken word. I was really moved – it had to do with earth. A few years later I called her and we started talking and decided to collaborate. She is very connected to Maori culture and collaborators. Then music came into the picture. She had just finished working with musician Dean Hapeta, so we decided this was going to be an international collaboration with the Maori; Kateri is Ojibwa. Kateri and I talked about our overall vision of connection to the stars. That is a recurring theme in my work, associated with the creation story and the connection to constellations and stars. It is the same way with Ojibwa and also with Maori, a lot of their legends have to do with the stars and the separation between the sky and the earth. I think the sky is the father and the earth is the mother and the children are the ones that separated them. We talked about all these stories and concepts.

The opening of the scene called “Life Force” is a solo that tries to capture the essence that I was talking about, connection with the spiritual universe. Raoul Trujillo played the ancient character and I played the grandmother who is passing away. All of this content comes directly from Haudenosaunee beliefs about what happens after you die; there are very specific and very detailed ceremonial funeral rights and beliefs. This scene portrays the aspect of the importance of breath; when you say it in our language “to die” means the breath has gone out of you. Raoul represents one of my ancestors on the other side, because when you are passing, someone will come and greet you and take you across to the spirit world. The movement in Kaha:wi is very full-bodied and expansive; you can see that we are used to using grounded energy. In the Gayowaga:yoh step, the fishing dance, the energy is down, the weight of gravity is down and the energy ripples through the body in a circular pattern.

Here on Earth is much more abstracted. It is about transformation. Again it was inspired overall by the creation story in which beings from the sky came to inhabit the earth below. In this part we're transforming from all matters of life, plants and animals, to eventual human form. It is much more expressionistic and raw.

In Constellation of Bones we used some specific Maori gestures, strong angular stances, and percussive breath. Again, it was very contemporary, with two simultaneous duets. Because it was also inspired by Kateri, one section was more influenced by grass dancing, as opposed to Iroquoian style.

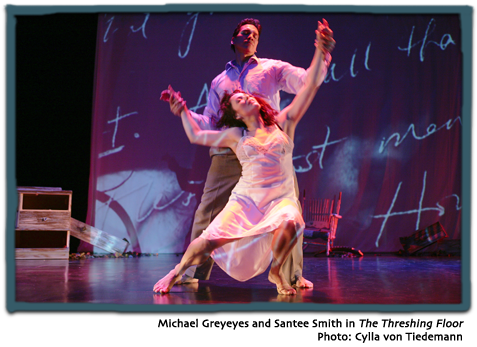

We premiered The Threshing Floor at Trent University Theatre and it was co-presented by Indigenous Performance Initiatives, directed by Marrie Mumford. She is really good at being able to bring in audiences from very diverse backgrounds, both aboriginal and audiences that are from Peterborough. Because Michael and I chose to do movement that was not overtly coming from a traditional dance background, and the theme wasn't traditional – our costumes were ordinary clothes – we were excited to see what the aboriginal audience would think. One lady said she saw herself on the stage because of this couple relationship, and that it was the most aboriginal dance she had ever seen. I see that as a little success, because it was showing identity through this contemporary couple and people could identify with that couple. It was actually the non-native audience members who had more difficulty with it because it went against some of their notions about what contemporary aboriginal dance should or would be. Their comments were along the lines of, “What makes that aboriginal?” or, “I didn't see any aboriginalness about it.” Michael would just say, “Well it's aboriginal because we are.” Michael is Cree and I am Mohawk and Shelley, the filmmaker, is Mohawk and our musician/composer is from the West Coast Nations.

A Story Before Time is based on the Iroquoian creation story. Kaha:wi and A Story Before Time have very strong connections to Iroquoian movement and knowledge bases. This piece was created initially for family audiences. We have developed a particular curriculum-based study guide to go with this production and a supplementary DVD that talks about the traditional content. It shows some of the traditional dance steps. We have a little group dancing some of the traditional dances and then I do some of the contemporary dance. That information goes out to the schools and the teachers work with it in their classes and then come to see the production.

A Soldier's Tale was a collaboration between Theatre Aquarius and the Hamilton Philharmonic. It was directed by Max Reiner who is now at the Vancouver Playhouse, and it was our Canadian interpretation of Igor Stravinsky's The Soldier's Tale. This is a piece that Max Reiner initiated. We talked about traditional and contemporary and how we were going to create this new version of the classical script and score, and how we would do this with our interpretation. We ended up keeping the script almost exactly the same except instead of “princess” I became the chief's daughter.

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni