CA: Carol Anderson

VT: Veronica Tennant

Q: Questions and comments

CA: Veronica Tennant is speaking as part of Choreographic Dialogues, a series that has been running at York and at several downtown venues since last fall. Choreographic Dialogues allows choreographers to speak about their work, and offers opportunity for exchange with listeners about their work. The series has been supported by the York Seminar for Advanced Research, and the Department of Dance. So thank you.

Prima Ballerina with The National Ballet of Canada for twenty-five years, Veronica Tennant won hearts and accolades dancing with luminaries such as Erik Bruhn, Rudolph Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov. Since 1989, she has garnered acclaim as a gifted filmmaker, writer, producer, director, narrator and actress, with her works winning several awards including the prestigious international Emmy award. Since forming Veronica Tennant Productions in 1998, she has produced and directed a large body of arts performance programming for television, including Celia Franca: Tour de Force, “best dance film of 2006” (The Toronto Star) and Shadow Pleasures inspired by Michael Ondaatje's book of poetry of the same name. This film won an unprecedented seven Golden Sheaf awards at the Yorkton Film Festival including “Best Director” and “Best of the Festival”. She had two new documentaries broadcast on Canadian television in 2008 – the critically acclaimed Vida y Danza Cuba shot in Havana and Toronto, which was screened at the Luminato Festival in Toronto in June 2008, and shown on Bravo! television to excellent reviews, as well as being invited to screen at the prestigious Havana Film Festival. Also in 2008, CBC broadcast Finding Body and Soul, an in-depth examination of the process of a play created by Judith Thompson.

Lauded as a great communicator, Veronica Tennant has also built an extensive reputation as a narrator, actor, coach, teacher and choreographer. She has received five honorary doctorates and has written two books. In 2001, Veronica Tennant was inducted into Canada's Walk of Fame. More recent honours include receiving the Walter Carsen Prize for Excellence in the Performing Arts, and the Governor General's Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement. In 2007, Veronica Tennant was movement director/choreographer for the successful theatrical adaptation of Margaret Atwood's play The Penelopiad, a collaboration between the Royal Shakespeare Company and Canada's National Arts Centre. She is a member of the National Arts Centre's board of trustees and, since 1992, privileged to be Canada's national ambassador for UNICEF. In 1975, Veronica Tennant was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada. In 2004, she was elevated to the rank of Companion, the country's highest honour.

Lauded as a great communicator, Veronica Tennant has also built an extensive reputation as a narrator, actor, coach, teacher and choreographer. She has received five honorary doctorates and has written two books. In 2001, Veronica Tennant was inducted into Canada's Walk of Fame. More recent honours include receiving the Walter Carsen Prize for Excellence in the Performing Arts, and the Governor General's Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement. In 2007, Veronica Tennant was movement director/choreographer for the successful theatrical adaptation of Margaret Atwood's play The Penelopiad, a collaboration between the Royal Shakespeare Company and Canada's National Arts Centre. She is a member of the National Arts Centre's board of trustees and, since 1992, privileged to be Canada's national ambassador for UNICEF. In 1975, Veronica Tennant was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada. In 2004, she was elevated to the rank of Companion, the country's highest honour.

We are delighted to welcome Veronica Tennant.

VT: Thank you. One of those honorary degrees was from York, so I'm very happy about that (laughter). Thanks very much Carol. I have to say it's very inspiring, the whole concept, the impetus for this conference, the whole idea of reading and writing dance, the synchronicity of words and music, of course words and dance and motion, but music also infusing all of that.

I'm going to begin by reading something from Margaret Laurence's autobiography, her memoirs that were published posthumously in 1989. She titled her memoir A Dance on the Earth. She says, “… women as well as men, in all ages and in all places have danced on the earth. Danced the life dance, danced joy, danced grief, danced despair and danced hope. Literally danced all these and more and danced them figuratively and metaphorically by their very lives.”

I stumbled upon this in the days in 1989 when the Globe and Mail actually had an Arts section and were running beautiful quotes at the top of that section. That was the year I had made the very difficult, momentous decision to leave the world of ballet, to leave the stage. And there was this quote one morning in the Globe and Mail. I researched it further and read Margaret Laurence's memoirs; she makes this analogy between life and dance all the way through it, and dance, for her, is her way of communication. Except – she then funnelled her life and dance through words into the wonderful literature that she wrote. For me it was very important at that time. Once a dancer, always a dancer. Yes, I thought, I can continue to dance. I'm going to dance the rest of my life – and by corollary with that came the thought, “I'm going to choreograph my life.”

Having come from a world where, as a ballerina, I was choreographed for – where my life in fact was programmed – it was a wonderful opening of ideas for me. When I did leave the ballet and moved on to expand into other careers and art forms, I found out for the first time that I was an “idea” person. Professionally, I did not know this during my first twenty-five years – because that wasn't bred into me in the intense world of classical ballet. And yet in that world, choreography and working with choreographers was the lifeblood. Even as an interpreter, the whole creative process and being involved with the creator can give you a pulse and a meaning that goes far beyond the technique of steps and the notion of perfection ... moving into the whole charting of a choreographic journey.

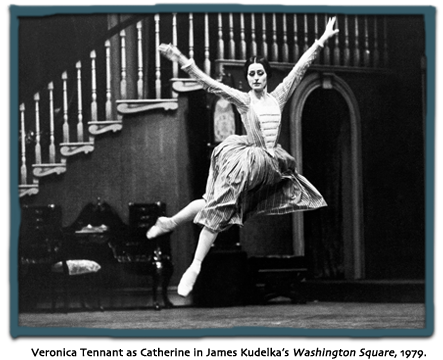

While I didn't work with John Cranko when he mounted Romeo and Juliet on The National Ballet of Canada in 1963, because I was injured and not yet in the company, I did have the privilege of watching and absorbing all his rehearsals. He was mesmerizing! And apparently, he gave Celia Franca his blessing for me to be cast as Juliet when I entered the company the following year. That was my first role. John Cranko, when he originally created Romeo and Juliet in 1962 (I danced it in 1965), really started a new form in terms of dance drama. This made Romeo and Juliet, in its way, revolutionary. I worked with Sir Fredrick Ashton, the peerless English choreographer, first through Celia Franca who was the artistic director of the National Ballet, and later in person when he came to coach his ballet – La Fille Mal Gardée. And I had wonderful experiences with Antony Tudor, Roland Petit, Flemming Flindt, Grant Strate and James Kudelka, who I think I can say that I helped at the very earliest part of his career. He had just joined the National Ballet. He was seventeen and we were touring Nureyev's Sleeping Beauty throughout the United States. I had really admired Goldberg Variations, a piece James had done at the National Ballet School. So I went up to this young kid who had just joined the company and said, “Are you planning to do any more choreography?” He said, “Oh no.” And I said, “How old are you?” He said, “I'm seventeen.” And I said, “Well, you'd better get on with it.” (laughter)

James came to me the next day and said “I have a piece of music.” I said, “Great, let's start.” And that was the beginning of our collaboration. He is indeed a superb choreographer, one of that rare breed of great classical choreographers, but a contemporary choreographer as well – James is extraordinary in his ability to use all the different vocabularies and to craft new ones.

I also danced Forgotten Land, by the brilliant choreographer Jiří Kylián. I created roles for some choreographers and with many – including Cranko, Ashton and Tudor – I did roles that they had created on others. You always believe and hope that you bring a fresh interpretation by working with the choreographer. I also worked with Ann Ditchburn, David Earle, Christopher House and David Allan, who is now professor of ballet at University of California, Irvine.

This was as a performer, dancer and participant in the creation; those experiences were intense and the lifeblood of my work in the ballet. I never was that turned-on by technique alone. That didn't interest me as much as going on a journey with a choreographer and taking those steps further. For my parting role in 1989, I chose Juliet because it was she who launched my career as a dramatic dancer and it felt like I was closing a beautiful circle.

Throughout the twenty-five years I danced, I appeared in many CBC Television shows and films. While I was proud and happy to be part of them, I felt the need to delve into a more interior world. I recalled everything that I had poured into a film as a dancer. I remembered the passion from the artists around me, but there were times when I felt that the results were not transmitted across the narrow, small television screen.

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni