CA: As a young choreographer, you made solos and investigated the language and the vocabulary and the syntax of movement by choreographing for yourself. Is your present experience similar to that?

CA: As a young choreographer, you made solos and investigated the language and the vocabulary and the syntax of movement by choreographing for yourself. Is your present experience similar to that?

CH: The change is – it's not enough just for me to do things by myself. So re-entering performance collaboration with Deborah, working on these solos, for example, it's Deborah's choreography and Deborah establishes a specific world in which this choreography exists. She presents a number of questions that we are considering all the way through. But at the same time there's tremendous freedom to adapt that choreography, and although you're on your own, you've got a director there all the time. That has become increasingly important to me, the experience of not being in charge of everything, being in a relationship with somebody else where you are discovering new things, and all of those new things you're discovering you're able to bring to your work and bring to your collaborators.

CA: Deborah, could you talk to us a bit about your notion of what the dancer is?

DH: Well, it kind of goes like this. All I've ever done is dance, and even though I tried to quit, as I told you, I wasn't able to. And I figure if all I've ever done is dance, I'd better make dance some place where I get to address some really big questions. I mean if this is the love of my life, if dance is more important to me than anything else, I'd better ask some very big, interesting questions in the name of dance. I can describe it right now – and this just took shape less than a year ago. What if dance is how I practice a relationship with my whole body, at once in relationship to the space where I'm dancing, in relationship to the people I'm dancing with, in relationship to time passing, in relationship to my audience?

So I give myself a really big job in the name of dance. And – it's also so impossible that I have to treat it pretty lightly. I treat it devotedly, but lightly, and I notice as much as I can. So that's the dancer for me, that's the dancer who I am, practising to be as fully as I can, and knowing I can't be that. Which is especially terrific. Not being able to be this. Not to be able to get it, I can't “get it”, and that's very un-American – so I really enjoy it.

CA: I've been reading some of your writing, and it's fascinating how you talk about dancers; you're not looking for display, but really a different kind of activation and a different kind of empathetic connection. Could you talk to us a bit about that? Your notion of dancing at the cellular level?

DH: It's like Christopher was saying – you could jump so high, you could turn so fast, you could fall to the floor, you could be as lyrical as you could be, you could be as abrupt and contracted and extended as you can be, but it's pretty limited. The three-dimensional body is pretty limited. I noticed that when I look at dance, I know after 32 seconds exactly what the movement vocabulary is going to be for the next hour and a half. I've gotten it down, I know it, I can recognize it. So I'm not interested in the limitation of my three-dimensional body. I thank God I have it. I'm grateful. But it is really limited, and especially as I get older, it's really limited. So, how do we get beyond limitations of the three-dimensional body?

One way I have been practising getting beyond the limitation of my three-dimensional body is reconfiguring it to my cellular body. I have to be here to reconfigure it to the cellular body. When I ask these questions, “What if?” I'm asking my cellular body, not Deborah Hay. I'm asking my cellular body for feedback. You've got to think it. Do you believe that we have been put here on earth with all of this stuff like feet and legs and hips and spine and then to carry a head around to do the act of perceiving? It doesn't make sense. So, I have been spending the last forty-five years of my life dropping the attention that keeps creeping up into my head down into my whole body. Asking questions from the whole body at once. I have no idea what the validity of this is, I just know that I stay interested in noticing the feeling from the whole body at once, from my bones, from my flesh, from the cells, from the mirror. Who knows how I do it? I try to invest my whole body with the kind of intelligence and voice – that's the dancer who's dancing. It's the whole body. That's where the voices are coming from. Coming from all over. Not just my head, not just the learned mind, but the way we have been programmed and choreographed. Right now I am just obsessed with how I have been choreographed by my culture, by my gender, by my belief system, by my genetics. I have been so choreographed. So how do I infiltrate that choreographed body and learn how to transcend it? I do it with tricks. I play tricks on myself all the time. And I'm saying that simply because this could be real heavy and I don't mean it to be heavy. It's light. Again, I just have to trick myself into noticing where I am. Constantly. My latest thing that's come up is that it's so easy to leave – I'm talking about the dance studio and working and practising. It's so easy to leave. The difficulty is being here and letting it go and being here and letting it go and being here and letting it go and being here and letting it go and being here and letting it go … and that's the dancer.

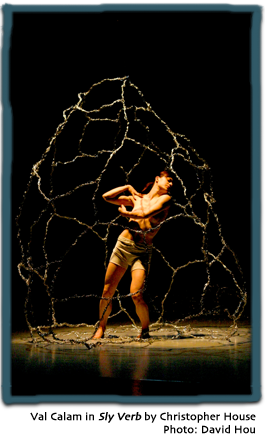

CH: Can I make a couple of observations? From my experience working with Deborah, but also watching Deborah work with others, and in particular with the Toronto Dance Theatre dancers in the last little while, on the essence of the choreography and of the performance practice – I feel that they're very much one thing. Form and content are absolutely linked, which saves a lot of time because you don't have to develop them independently. The essence is developing what to me is an unusual awareness and sensitivity when performing, which is instantly shared with the audience. Through an idea – Deborah uses these words and I think it's so beautiful – she talks about “inviting being seen” rather than showing. So there's a very gentle aspect to the work. The experience in doing work – and I think the TDT dancers who are here who have worked with Deborah will probably concur – that the experience of doing this, because of this heightened awareness and because of the idea of working within this laboratory where your visual field, your sensual field, and I think it can be broader than that, is providing you with all the information you need to keep you in the present moment. So you are looking at every person around you. You're assuming that they're doing what you're doing and you really assume that they're practising what you're practising. The act of doing that, to me, enlivens the space between the audience and the performers and does a beautifully dynamic job of enlivening the space between the performers themselves in a group because they are so aware of each other and so automatically empathetic, so no one is ever acting. In fact it's a by-product of the practice. Any thoughts on that?

DH: Yes, I would say it's not a by-product. I would say it's primary. It's absolutely something that's going on. We're all involved in the same experiment but everybody's having a different experience.

CA: Is it possible to talk about the work you're doing with the TDT company here?

home l shop dcd l history l links l donations l the collection l services l shipping policy l CIDD l exhibitions l CDFTP

educational resources l visits & lectures l making archival donations l grassroots archiving strategy l personnel l RWB alumni