|

|

| |||

|

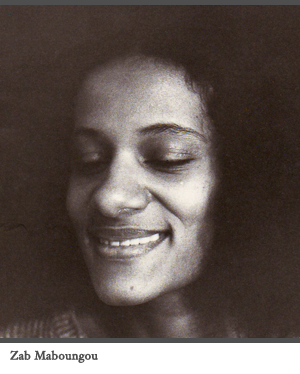

Zab Maboungou, choreographer and performer, founded Zab Maboungou/Compagnie Danse Nyata Nyata in 1986 for the creation and promotion of her work in a local, national and international context. This prolific artist is active on many fronts: as a choreographer, performer, music composer, author, and teacher of philosophy and dance, she works to develop and promote African dance in Quebec, across Canada and abroad. In 1995, Maboungou presented the premiere of her solo Reverdance at New York's Lincoln Center. In 1996, the same piece was a resounding success at the Pan-African music festival (FESPAM) in Brazzaville, in the Congo. Her solo work Incantation was presented in a number of Canadian cities by the CanDance network, including Vancouver, Montreal, Toronto and Halifax, in 1997. The same work had its American premiere at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., in February 1998, and its Asian premiere at the Pusan ans Taegu International Dance Festival in South Korea in April 1998. It was also programmed during the Festival International de nouvelle danse à Montreal, and at Cameroon's Rencontres théâtrales internationales in 1999, as well as the Italian festival “Nuovo Danza” in November 2000. In May 2001, the piece travelled to Germany. Mozongi, a work for four dancers and two musicians, toured from 1997 to 2001, and was presented at Montreal's Place des Arts in January 2001. Maboungou has been teaching the technique “Rhythms and Movement” in Montreal for twenty-five years. She has developed a unique style and teaching method called “the rhythmic of breathing” that she describes in her book Heya… Dance !: an historic, poetic and didactic treatise of African dance. This method has led to a technique involving rhythm, posture and alignment which is named “lokéto”. Maboungou has also taught Western philosophy at Laval's Collège Montmorency since 1982. Her reputation as an artist, thinker and activist is well-established, and she has been invited to hold workshops in universities and cultural centres in such locations as Halifax, Toronto, Vancouver, Washington, D.C., Boston, New York, Dakar, Zimbabwe, South Korea, Congo, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and England. Carol Anderson's conversation with Zab Maboungou took place in Montreal, at the Nyata Nyata Studio, May 31, 2012.

|

|

|

Excerpt from Maboungou's Reverdanse

I started dancing in Africa. Dance was all around me – everywhere, all the time – with the life, with the people. My mother died there. This is a huge event in Africa. You don't go to a funeral for one or two days. This is one thing that is strange to aliens. Non-Africans may be waiting for their employees to come back to work, thinking, “Come on, people die all the time!” and they're shocked when two weeks after a death, the families are still in the village. In Africa, death is not about “Let's get on with it.” Death is about life. Death is actually about organizing life, in Africa. I saw this many times. I saw this when my mother died, and in other families – days and nights of dancing and singing, events happening; we were in the middle, we were surrounded by this, all the time. Plus, this was a country that had declared its independence, as did many African countries - the 1960s were years of African independence. It goes with the civil rights movement in the USA, and even the fight for Quebec. Quebec at the time was very much attuned to Africa, and even activities of the Black Panthers, because they were following events worldwide; there was this movement for change happening in the whole world.

I was very aware of social change, because my father was very much into it. He met Che Guevera, and many other people connected to ideas of transforming the world, and questioning culture; questioning power relationships in the world, and therefore cultural relationships. Since my mother was French and my father was Congolese, I was right in the middle of it. Influenced by the example of the Chinese declaration of the need for a cultural revolution, there was a cultural revolution in Congo. Leaders said, “We need to pay attention to our traditions.” The good intentions of the time said, “We need to purge what is bad, and keep what is good of our traditions.” Who would not say that of any tradition? In order to achieve these good intentions, a lot of attention was paid to music, of course, and to oral history, as a way of telling time, and being in time. With good intentions, my father, who was an intellectual, really exposed us to a wide cultural range. We attended lectures, heard music, went to literary events as children, so I was educated in that aspect also.

I was very aware of social change, because my father was very much into it. He met Che Guevera, and many other people connected to ideas of transforming the world, and questioning culture; questioning power relationships in the world, and therefore cultural relationships. Since my mother was French and my father was Congolese, I was right in the middle of it. Influenced by the example of the Chinese declaration of the need for a cultural revolution, there was a cultural revolution in Congo. Leaders said, “We need to pay attention to our traditions.” The good intentions of the time said, “We need to purge what is bad, and keep what is good of our traditions.” Who would not say that of any tradition? In order to achieve these good intentions, a lot of attention was paid to music, of course, and to oral history, as a way of telling time, and being in time. With good intentions, my father, who was an intellectual, really exposed us to a wide cultural range. We attended lectures, heard music, went to literary events as children, so I was educated in that aspect also.

So – through history, stories, life, death and transformation, and through cultural transformation – this is how I entered dance.

At a very young age I participated in the circle of dance; this was traditional dance where you were allowed to participate. I discovered very early on, at seven or eight, that I was equal to an eighty-year-old person when it came to the circle of dance. It was important for me to feel that equality – I had already been stripped of power myself, with my mother gone, and it was hard for my brothers and I to situate ourselves; we were “part”, mixed-race children learning to situate ourselves in a world where everyone says, “So, you're half this, you're half that.…” Half is very hard to understand.

So all of this was already there, present for me, immediately, right in the middle of the circle. I was small – and I know I haven't grown so much – and then I knew my true home was right there. Dance told me everything there is to know. And that hasn't changed. That idea hasn't changed, and I'm very pleased that I still do have a memory of something, when I was so young, that is still as fresh, and mysterious and powerful as it was then.

For the immigrant that I became, dance was definitely home.

When I came to Quebec, there was no African dance. I started it … I know it's funny to say, when I came, everybody told me there were no university programs of study, and you can't apply here or there, we don't know your form of dance, and there's nothing for you. You might think, okay, better to go back where you came from. But I stayed, because of the people who were interested in the dance, not because of the institutions. (next page)

CA: Thank you for finding time to speak with me Zab. Can you describe your journey, deciding to emigrate, and coming to Canada?

CA: Thank you for finding time to speak with me Zab. Can you describe your journey, deciding to emigrate, and coming to Canada?