|

next page l previous page I didn't have initial training in dance, I had an experience of dance. My grandmother was a displaced woman, living in central Iran, which is mostly Persian-speaking, and she spoke only Azerbaijani. She had a room, and she had me as an audience. I remember her when she was in her nineties; she would sit in her room and use her hand drum and her bamboo fan, and she would tell me about her homeland – about Baku, about the dances, the weddings, about the way people sit, about her sisters' dangling earrings and silk scarves, and their hair – and why you have to have two braids … because the fairies are dancing between the braids.  I opened my eyes to seeing a displaced woman trying to use music, dance and storytelling so strongly and so effectively – so I have these memories, as if I've seen a movie. I remember the streets of Baku and her father's home visually. I don't remember the words as much. Even now, when I'm talking to anyone about this, I first see the picture and then tell them what I've seen in the picture, in my mind. So – she transformed that little room in central Tehran to her home in Baku with dance, music and storytelling. This was my experience. I opened my eyes and grew up with that. I opened my eyes to seeing a displaced woman trying to use music, dance and storytelling so strongly and so effectively – so I have these memories, as if I've seen a movie. I remember the streets of Baku and her father's home visually. I don't remember the words as much. Even now, when I'm talking to anyone about this, I first see the picture and then tell them what I've seen in the picture, in my mind. So – she transformed that little room in central Tehran to her home in Baku with dance, music and storytelling. This was my experience. I opened my eyes and grew up with that.

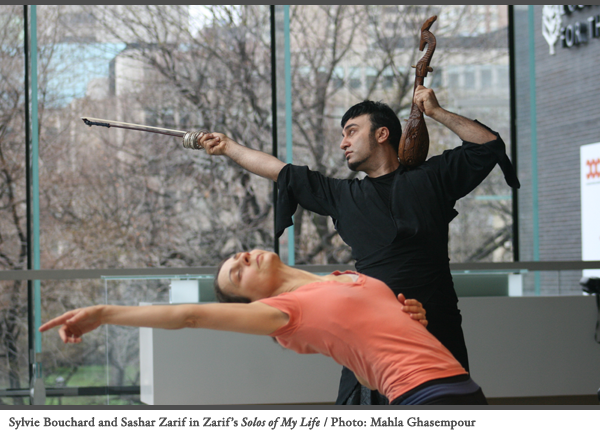

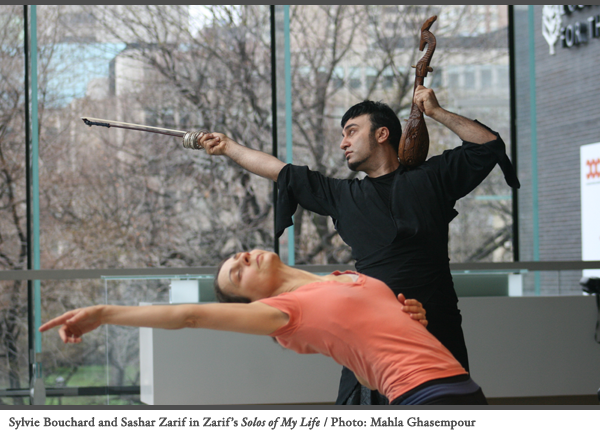

Then, because she couldn't get up and dance – she was old – she trained me to be her legs. My first employment in dance was as my grandmother's legs. For us it wasn't a bedtime story she was telling me. She was telling me this history and knowledge from 9:00 in the morning when my mum left me with her, until night. Even when we ate, she would always connect it. When I was back in Tehran in 2006, after so many years, and found that house, and saw that little room, it was so small. It had no balcony, only tiny windows. What I remembered was a huge room with huge windows and balcony, because she made me feel it that way. When I left engineering and attended to dance, I was not satisfied with just the movement and following the music and wearing any costume. My costumes had to be exactly right. The Azerbaijani costume looks a lot like Victorian women's costumes – very tight coat, long skirt and a frill on the bottom of the jacket. The jacket is also like a pushup bra, has a very open front. The jacket has to be so tight, so tight that you have to lift yourself. When I was first making my costumes here, my dancers always complained – “I can't breathe!” But that is how it's supposed to be – that's the whole beauty of it. I wasn't satisfied – my field was more dance and culture studies, more than movement, it was all the elements that accompany, or echo, or initiate the movement, or drives it – all the aspects. I went to York University, and I couldn't explore that at the dance department; a friend of mine – a photographer who did beautiful work – saw how much I wanted to do this, and called Nina de Shane, then the director of cultural studies. She said you can do dance, it's very open. I remember we sat down and made a portfolio of dance pictures my photographer friend had taken of me over a couple of years, and she helped me write about what I was doing. Azerbaijani dances have a therapeutic aspect and I was very interested to know about all this … and to understand the magic in the form. Nina de Shane was very supportive, and I embarked on cultural studies.At that time, Norma Araiza and Zelma Badu were both doing Master's degrees in dance – they were doing a course called “The World of Ritual”. It was great – I still use material I learned in that course. “Arts and Identity” was another course that Nina de Shane taught. That was so helpful – it opened my eyes to the world. She was talking about hip hop – and the way she talked talked about it, the seriousness of the way she talked about the dance, and graffiti – made me realize that any expression in this world is so important and valid – and there is no better or worse. I realized I should not feel marginalized, or think what I do is not important. So I pursued that investigation for most of the rest of the 1990s. I'd formed an Azerbaijani dance group here already, and trained students – from Iranian and Azerbaijani families – from 1993 to 1997. They danced well, these teenagers; I was very strict with them. We performed at one of Zelma Badu's shows – Patrick Parson was there, and some others from the Toronto dance community. And they all said, “This is great! Fantastic! What is this?”This connected me to the dance community. Then I took a course with Menaka [Thakkar] and got into that, and then started collaborating with an MA student – an Odissi dancer, Sarala Dandekar, at York. I worked with her, and started collaborating with her and with other people in different genres. Then I realized reconstruction was not what I wanted to do; while I love the form, it is historical. These costumes are not used anymore. The dancers are not being informed by the social level of everyday life. It was a stage dance. Also, whenever I was doing a workshop anywhere, the comments were, “Oh this is so much fun” and “Oh this is so interesting.” I just didn't like that! I felt I had so much invested in this – it was as important and intelligent as anything else. I decided to stand back and explore – How can I connect? How can I be part of this community? Give them what I know in a way that they would understand it.Excerpt from Zarif's Solos of My LifeIn 2001 something else happened in my life. I was quite shy. I had a speech coach I was going to for awhile – I was very shy socially. He called me one day and told me to go see a man called Paul, at Marcel, a French restaurant on King Street, downtown. I said sure, went to Marcel and saw Paul, who told me I'd be working there, as a waiter. I said, “What? I would have a heart attack!” I respected the teacher, but called him and said, “This is the worst job for me.” He said, “No, it's the best thing for you.”I started working there. I learned how to serve wine. In the first week, a couple came in; I opened the wine and served her, and was about to serve the gentleman. They were conversing – I don't know what happened – she threw her wine in his face! I didn't know what to do – put the wine down? Keep pouring some for him? Pour more for her? Disappear? She said, “You can just leave the wine and go.”The manager said, “Thirty years in the biz, and I've never seen anything like this! I'm so sorry.”It took me six months to let go, to relax, to walk comfortably, to not have muscle spasms in my back and shoulders – I was tired and so tense, carrying plates. But that job really changed me. I was friends with everyone there. Then one day, I walked into the restaurant and a very good friend walked in and said, “Oh I wish they'd put a bomb on all Muslims and kill them. Kill all of them.” It was 9/11. Then, my fears of all those years came back to me. I have a friend in Pefferlaw, Ontario – I called her and said “Something happened. Can you hide me and my mum in your basement?” She said, “Of course, I'm worried too …” Then I thought, I really need to do something with this, I can't be angry. I have to channel this; I have to say what I have to say. After that experience at Marcel, I came home and promised myself not to do anything other than dance, even if I starved.On September 29, I walked into the office of the director of community programming at Harbourfront, Sheila Tang. I walked into her office – I don't know how – and sat down and said, “I'm a dancer and I want to do something. I want to start a festival called Dancers for Peace.” I had talked to Norma Araiza, Jerry Longboat, Yasmina Ramsay, Elena Quah, Junia Mason – a group of people, and asked if they would perform for free. I said to the programmer, “Would you help me?” And she said, “Of course.” We did the first Dancers for Peace a month after that at the Harbourfront Centre.

A week after that, someone who was visiting from Spain called me and invited me to Barcelona to do a workshop in the fall. Then I sat at the computer and sent an email to schools in Germany that I found online – and said “I'm going to Barcelona, this is what I do … Would you like me to stop by?” Casual, like that. A woman from Cologne contacted me and said there were several sponsors – in Cologne, Freiburg, Munchen and Frankfurt – who wanted me for a one-month tour. That was the start of my travelling. One thing led to another and I started dancing a lot. These travels were very good because I was going from one culture to another. Even within Germany, from Freiburg to Frankfurt there is a big difference culturally – it's like day and night. Then in Barcelona – the way you have to talk to people, and their level of connection – some are more attentive, some more musical – so it was a great experience for me – very educational. Also, to be able to transfer to them what I had; to make it acceptable to them, make them understand that a shoulder accent, a sigh, the coquettishness, a veil on the head, were tools, a language. People wanted more and more – and I wanted more and more too. I started taking my money from touring and going to Central Asia – Azerbaijan and Iran – to do more research. On my way back to Canada, I'd stop again in Europe, and give them this material first-hand. I also used my research material in teaching and creating back in Canada. Before I knew it I had an organic system going for me. Later on I realized that this idea of research, education, creation is an organic design, and this is how I function. Also, it was so satisfying for me. I started teaching at York, it was quite well-received. They did so much work, those students, and put in so many hours. I loved it because I could give them more than just the moves – I could give them understanding, talk to them about cultural space. The first time I did this in a class was tremendously satisfying. I hate war – everything to do with it. Because of my experiences, I hated arguments, I hated war, I hated hate. I saw a woman on a bus yelling at this little Chinese lady who was elbowing her way through a streetcar in rush hour and I got so upset. In class, I always project personal experience within the larger environment. After this subway incident, I was teaching Kurdish dance, in which dancers are shoulder to shoulder, you lock elbows tightly – the dancers are very close to each other. Then you have to do a circle dance, jump, and lift the shoulders all together up and down, together. Then I told them to stop. Most of the kids were very uncomfortable to be into one another's space in this way. I said, “It's uncomfortable in our culture to be so close, so into each other's space. I understand, you need your personal space – culturally, I do too. When I go back to Asia, after living here – I take that personal space with me, and I need that. But you have to understand, to learn this dance you have to be able to co-exist in each other's space. When you look at this dance, you see how they handle the space. If you know this, next time you're in the subway, and there's someone pushing you (I brought up the example of the little Chinese lady) it is wrong, you wish she wouldn't do it – but you wouldn't ruin your day and create hate because you think she's ignorant – you would know this is how she relates to space; she's not trying to push you. This all came out without me really processing it, and it was one of the most satisfying moments of my teaching. I thought, “I'm contributing – this was bigger than just movement …” I told them that by no means am I justifying the action, but I'm working toward understanding it. That is the first step; sometimes we try to solve before understanding.That put me on the right track and helped inspire me to use dance for what it really is – not a commodity but a necessity. This all comes from my initial experience with my grandmother. We were not only having a good time together – not all her stories were happy. Sometimes she would cry. When Azerbaijani women lose someone, they sometimes go to the grave and they sing for them. It's beautiful that you can actually incorporate movement and dance into all aspects of grief, happiness, joy, in order to understand something. That's what inspired the modal system of music in the East – the classical system is based on theme and moods – sorrow, sadness, excitement … like major and minor in Western music. They are divided into different intervals, so any music can be categorized according to mood, which has to do with the psychology. (next page) | |

I opened my eyes to seeing a displaced woman trying to use music, dance and storytelling so strongly and so effectively – so I have these memories, as if I've seen a movie. I remember the streets of Baku and her father's home visually. I don't remember the words as much. Even now, when I'm talking to anyone about this, I first see the picture and then tell them what I've seen in the picture, in my mind. So – she transformed that little room in central Tehran to her home in Baku with dance, music and storytelling. This was my experience. I opened my eyes and grew up with that.

I opened my eyes to seeing a displaced woman trying to use music, dance and storytelling so strongly and so effectively – so I have these memories, as if I've seen a movie. I remember the streets of Baku and her father's home visually. I don't remember the words as much. Even now, when I'm talking to anyone about this, I first see the picture and then tell them what I've seen in the picture, in my mind. So – she transformed that little room in central Tehran to her home in Baku with dance, music and storytelling. This was my experience. I opened my eyes and grew up with that.