|

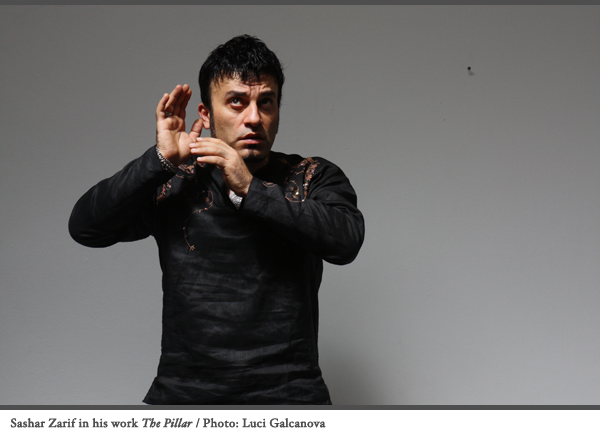

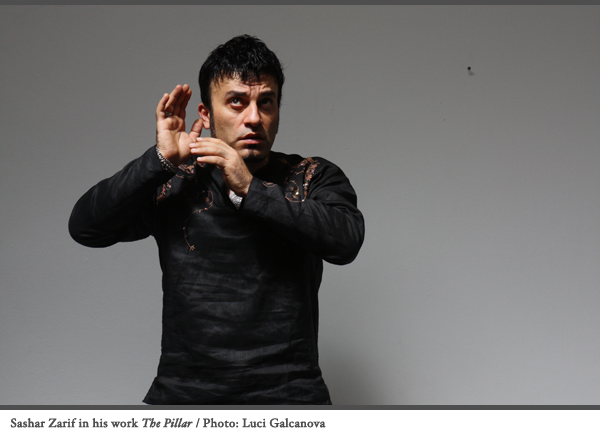

next page l previous page Sashar Zarif is a multi-disciplinary performing artist, educator and researcher whose artistic practice invites a convergence of creative and cultural perspectives. His interests are identity, globalization and cross-cultural collaborations. His practice is steeped in the artistry and history of traditional, ritualistic and contemporary dance and music of the Near Eastern and Central Asian regions. He has toured across the Americas, in Europe, North Africa, Central and Western Asia and the Middle East, promoting cultural dialogue through intensive fieldwork, residencies, performances and creative collaborations. He is the recipient of numerous national and international awards for his collaborations with outstanding Canadian artists, along with international icons such as Alim Quasimov (a collaborator on Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road Project), and universities and arts institutions across continents. Zarif is a research associate at the York University Centre for Asian Studies, a sessional faculty member of York University's Dance Department and on the board of directors of Dance Ontario and the World Dance Alliance - Americas. Among recent awards are a Chalmers Fellowship, New Pioneers Award for Arts and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. Sashar Zarif's conversation with Carol Anderson took place Monday, March 26, 2012, at the Dance Umbrella of Ontario, Toronto.

CA: What is the story of your immigration to Canada – when did you come here, and what is the story of your journey? SZ: My coming to Canada was not premeditated – I didn't decide to come here, I was forced to run away from Iran, where I was born. I escaped through the mountains into Turkey. In Turkey I went to a United Nations commission for refugees and applied for protection as a refugee. Then I lived in refugee camps, governed by the Turkish government for a few years, before the UN arranged interview opportunities for camp dwellers as possible immigrants to various countries. One of these places was Canada. It was just by fate that I was picked by a Canadian. I had an interview with a Canadian diplomatic agent – it was a short interview and I was very young. I remember after ten minutes the gentleman shook my hand and said, “Congratulations! You're a Canadian….” I waited for a couple of months for paperwork and I arrived in Toronto as an immigrant. I was in camps for about three and a half years. When I came to Canada I was eighteen. I was alone here. When I left Iran, my parents were in Iran. I ran away. I couldn't take it. I was arrested in Iran – the reason was music and dance and instruments and books. I was imprisoned. I went through torture daily, and I got an internal infection because of the beatings … and then I was hospitalized. When I was out of hospital, my parents arranged for my escape, through the Kurdish nomads that live in the borderland between Iran and Turkey. They paid a lot of money to them. I was taken away, though I wasn't sure where they were taking me. I was handed from person to person along the way. We went through a lot until I got to Turkey; I thought Turkey would be it ... I think this will come up when we talk about the artistic work, so I reference it now. I remember I left thinking, “This man is going to take me to Turkey and it will be over.” But he took me to a garage. Another man hid me under buckets in the back of a truck; they fitted the buckets over me. They drove about twelve hours to the border. Along the road there were searchers who banged on the walls of the truck. Then I thought, “I'll come out of the truck and that will be it.” But then, a man told me there was another car driving beside us, and I had to jump from the truck and into the car without either stopping. I thought that would be it. Then we went to the mountains, and had to climb through the mountains. After every hill, I thought that would be it. We got to the Turkish border. I thought that would be it, crossing the border, but then we went from village to village until we crossed from eastern to the most western part of Turkey. Then I thought that would be it. Then the United Nations, and the refugee camp, I thought that would be it. And then coming to Canada … and becoming a citizen, finishing my schooling … I thought that would be it! It's continuous. You don't know when the challenges will ever stop … as you take more in, and become more aware – not that I'm hopeless! (Sashar laughs)CA: Did you dance in the camp?SZ: I actually used dance to survive. We were illegals in Turkey. They saw our papers from the UN, but they took us in and questioned us. I could have said anything to them. Anything. Any name. But I kept my real name. They questioned us, and gave us temporary identity papers that said “Nationality – Stateless”. I was stateless for seven years of my life – those years in United Nations camps, and in Canada – until I became a citizen.

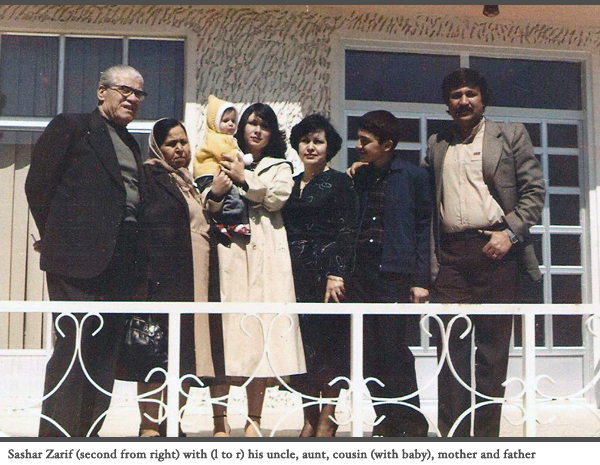

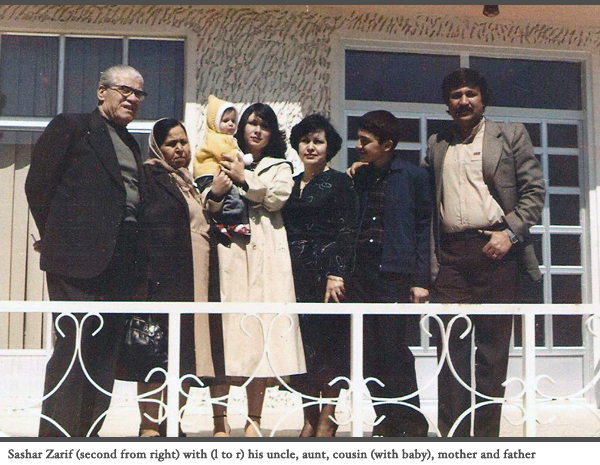

They moved us to the eastern part of Turkey, near the border of Iran. A lot of people were deported … you never knew who was going to be next. When these initial interrogations finished, they moved us to another camp, in the middle of Turkey in a very remote town. We got there at 2:00 in the morning, and they didn't have a place for us. So they took us to the police station and packed us into the cells. To give you a picture of who we were – we were all “home boys” – until a couple of weeks before, none of us had experienced street life – we were educated, we were at school, or at home – we were not street smart. I was the youngest. Because of my background I spoke Azerbaijani, and I knew some Turkish songs that I liked. When we were in these cells one of the guys said, “Oh, I am thirsty, and I have to go to the washroom!” but the guards wouldn't open the door. He said to me, “Sing a song, they might like it, the guard might at least open the door.” I remember, I associated singing with a sense of rejoicing, with expression, with release of tension. In that moment, I felt I was at gunpoint. I started singing. That was my weapon too – not as assertive as a gun, but it was my way of survival … this boy standing behind bars and singing this Turkish song, which is very happy. The guards were laughing. Then another man, who I later found out was the head of the police department, appeared in the back. He was tall, a strong man, with a strong face. I remember I was really pushing my breath, almost suffocating I was so scared, and thinking “What is going to happen, these guards could kill us.” I remember looking at him to try to read his eyes to see what was going to happen if I went on. And I saw his eyes were teary, this man had tears in his eyes. Then he shouted at the guards. “These are all kids. Why are you locking them in? Leave the doors open! Bring them some tea and fruit.” So that was one of the things I did. Now, every Nowruz, every first day of spring [the celebration of Iranian New Year], I organize a party … with singing and dancing, and I invite the police to come! I wrote a lot when I was in the camp. I used to write a letter every day to my mum, twelve or thirteen pages. When we got reunited after about seventeen years, when she came to Canada for the first time, she carried two suitcases, one small, one big – and in the small suitcase were all the letters I had sent. But I had seen her before that. In 1993, I returned to Azerbaijan. I have to explain why. When the Soviets took over and Azerbaijan became a Soviet republic, my grandparents left Azerbaijan and migrated to Iran. Then, after the de-unification of the Soviet Union, my parents went back to see their mother's land, their father's land. And of course, I wanted to see my grandparents' land so I went to see them there. That is when I started dancing seriously, though I was studying systems design engineering at the University of Waterloo right then. I was depressed before I went to Azerbaijan. The university counsellor said – “Maybe you need to see your parents.” I said, “Okay.” So I went to Azerbaijan – I was in love with the music and dance and decided to do a degree at the Choreographic Institute. They said, “It's going to take three years,” and I said “I'll do it in one year.” I used to take classes from 8:00 in the morning until 9:00 at night – dance classes, and music classes, and language classes. I finished it, and came back to Toronto, and worked a little – at Toronto Western Hospital in the biomechanics lab – and thought “I can do the dance on the side”. After I realized that it was not possible, I left my job. When I wanted to study dance I didn't want to jump up and down – I went to the dance department at York University, but there was no place for me back then. I wanted to study not just dance but also culture – for me dance was never isolated. I always sang and danced – I was introduced to this form by my grandmother. (next page) | |