Presents

Maud Allan - An Edwardian Sensation

Crime of the Century: Darkest Secrets Revealed

As her confession echoed across the courtroom, Maud was beside herself. Her character was questioned and her reputation was ruined. In a 1918 libel suit that went horribly wrong, the renowned dancer was forced to reveal her darkest and most precious secret … Maud Allan was the sister of a murderer.

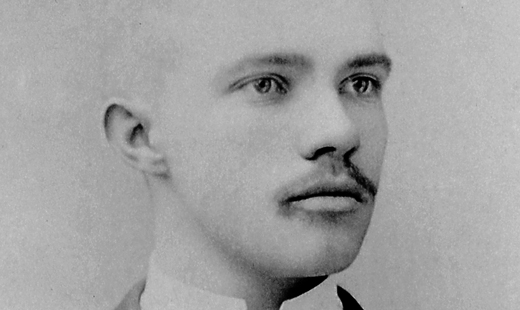

In 1873, Maud Allan was born in Toronto as Ulah Maude Durrant. Around age six, she moved with her family to San Francisco. Maud exhibited extraordinary piano skills – a talent that her eccentric mother was all too eager to exploit. Isabella Durrant was tired of depending on Maud’s idle father who found insufficient work as a shoemaker, and was convinced that Maud would bring their family fame and fortune through her musical genius. Unsurprisingly, Maud felt closest to her brother Theo.

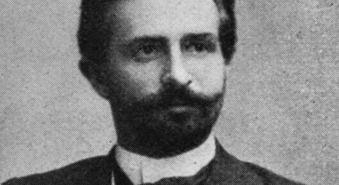

When Maud moved to Berlin in 1895, she aspired to become a prominent concert pianist and trained at the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin. It was also in Berlin that Maud first met Marcel Rémy, the composer who would later help her realize her concepts and who wrote the music for her chef d’oeuvre The Vision of Salomé. They met at a dinner party in Berlin following a concert by her close friend and mentor, Ferruccio Busoni, the renowned Italian composer, pianist and conductor. Interestingly, while a piano student, Maud frequently complained of stage fright, which, in her personal papers, she noted prevented her from participating in prescribed student recitals. Although she never overcame “the difficulty,” she managed to control it as a dancer.

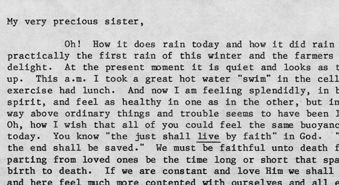

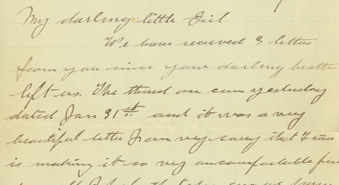

Back in San Francisco, brother Theo took a great interest in Emanuel Baptist Church. He joined the choir and worked at the Sunday School, all while attending Cooper Medical College. On the day of Maud’s departure for Berlin, she kissed her brother on the cheek and affectionately cooed, “Be a good boy, dearie, and be sure to graduate” … Theo was not a good boy.

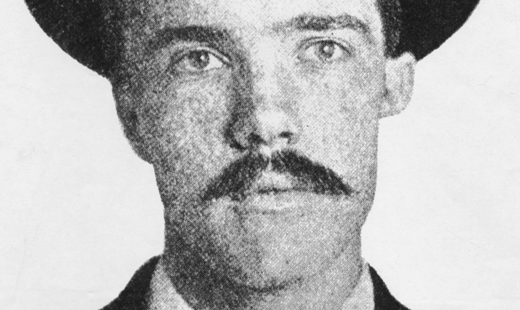

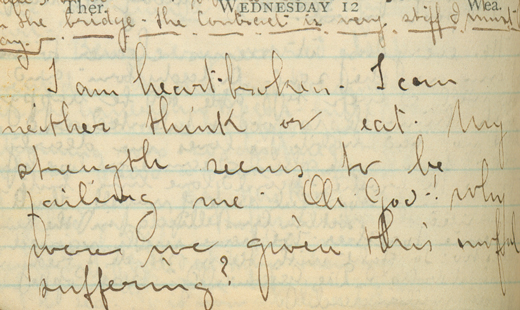

Within two months of her leave, Maud’s beloved brother was arrested for the brutal sexual assault and murder of two women in his church, Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams. Due to the hysterics of their mother and the press that followed his very public trial, Theo’s case was coined the “Crime of the Century” and he was often referred to as the “Demon of the Belfry”. After his execution was reprieved on three occasions, Theo was finally hanged in San Quentin Prison on January 7, 1898.

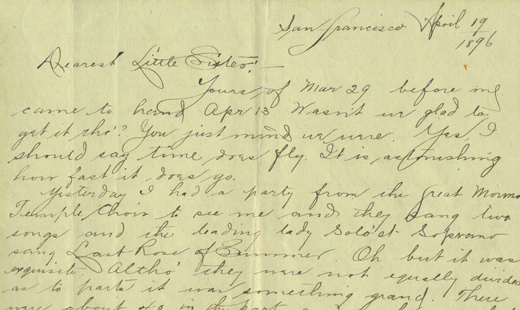

Maud’s mother and brother both wrote articles for the San Francisco Examiner. In its June 6, 1897 issue, the newspaper headlined two statements related to Theo’s scheduled execution. The first of these articles, accompanied by a portrait of Mrs. Durrant, was titled “Why I Will Be Present At My Son’s Execution.” The second, a two-paragraph statement in Theo’s handwriting, bore the headline, “Why I Am Willing That My Mother Witness My Execution.” Theo’s mother conducted various media schemes like this to raise funds for his trial – most of which just further publicized his case.

For more on the trial and a series of historical images, visit the San Fransisco Chronicle here.

Maud was convinced that Theo was innocent. Her family forbade her to return home, so she changed her name, stopped associating with her American friends in Berlin, and lived a tormented life abroad. On the outside, Maud was an impenetrable mask of propriety and discretion, but inside, her pain and anguish grew. Shortly after her brother was executed, Maud abandoned the piano, which was no longer an outlet strong enough to contain her emotions, and, at the age of twenty-eight, she channeled her sorrow into dancing. Guided by her extreme musicality, she called her interpretations “musical impressionistic mood settings”. She made her debut in Vienna in 1903.

Theo and Maud had a very close relationship. After his execution, she was unforgiving of society for making her the sister of a murderer; the trauma caused her to become increasingly ruthless, manipulative, and selfish. But her anguish also drove her artistically, eventually resulting in her passionate and provocative interpretation of The Vision of Salomé.

Not only did Maud suffer emotionally, but she also struggled financially. During the tragic event, Maud received very little money from her family, so she needed to work while pursuing her piano studies. Maud supplemented her income by illustrating sections of the Illustriertes Konversations – Lexikon der Frau. Nearly 900 pages long, the Lexicon provided women with information on a vast range of topics such as home economics, cuts of meat, darning and knitting, art history, plants, home lighting, medical remedies, and human reproduction and midwifery. According to the research of Felix Cherniavsky, Maud illustrated a section on obstetrics and reproduction.

In order to make ends meet, Maud also joined with some friends in a new business endeavour making corsets, which she designed, sewed and even sometimes modeled. Maud was a highly skilled seamstress. Throughout her career, she designed her own costumes and, at least initially, was her own seamstress. It has been speculated that Maud had a hand in creating her renowned Salomé costume.