Presents

Maud Allan - An Edwardian Sensation

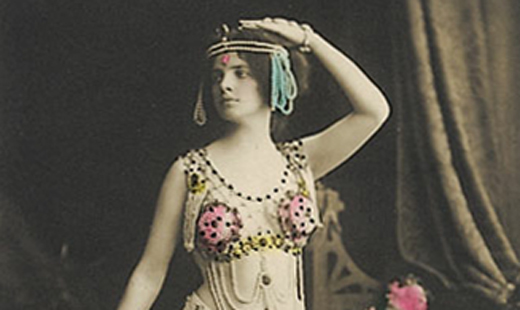

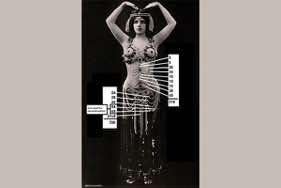

The Salomé Costume

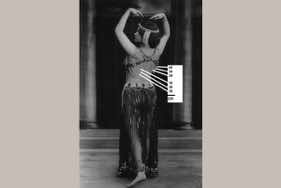

Maud Allan first wore her infamous Salomé costume in 1906 when she debuted her choreographic work The Vision of Salomé in Vienna. Salome was the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of Herod II and is famous in Christian iconography for demanding the head of John the Baptist as a reward for performing the dance of the seven veils. She is often depicted as a femme fatale – a mysterious and seductive woman who charms her lovers, then leads them into compromising situations. Irish playwright and poet Oscar Wilde embraced this motif in his play Salome, which inspired Maud Allan’s famous dance performance. The play, originally written in French, was to be performed by Sarah Bernhardt in 1892 but was banned by a British law that forbid the depiction of Biblical characters on the English stage. When the work went into production for a private performance in 1918, Maud accepted the principal role – a decision that would ultimately lead to her downfall due to its association with the notorious Black Book libel case.

Maud Allan had at least two Salomé costumes – both of which are now housed at Dance Collection Danse (DCD) – Canada’s national archives, museum and research centre dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of Canada’s dance history. The costumes, along with several artifacts and documents, were donated to DCD in 1996 by the late Felix Cherniavsky, whose father and two uncles performed together as the Cherniavsky Trio that toured with Maud Allan.

Why were there two costumes? It was necessary to have a backup because by 1908 she had already become an international dance sensation and by 1910 was celebrating her 250th performance at the Palace Theatre in London. It is quite possible that she had more than the remaining two costumes considering that she toured the work all over the world. To date, the widely circulated images of Maud Allan at the height of her career in 1908 only show her wearing the costume that has a black skirt with gold embellishments and the highly bejewelled brassiere. The second costume has a skirt that is primarily purple adorned with a scarab, and a matching brassiere echoing the turquoise colour of the scarab and the purple in the skirt. Both included headbands with a large rhinestone on one and a scarab beetle on the other, each mounted on a spring so that the decoration bobs. In postcards, Allan is wearing hand and wrist jewellery that seem to be lost to history now.

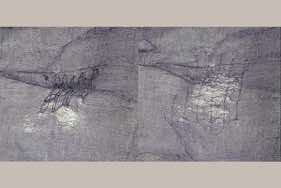

More than a century later, the garment was in dire need of care before it could serve as the focal point of DCD’s 2016 exhibition Maud Allan: An Edwardian Sensation. Over time, the choreography stressed the fabric where Maud Allan would have been kneeling, potentially due to the movement needed to rise from the floor to a standing position. The damage required the garment to be repaired multiple times and the resulting instances of darning have become a part of the object’s history. The silk had also become increasingly fragile, the metal bodice had begun to corrode, the beadwork was falling apart, and wax had been spilled on one section of the purple skirt.

In 2013, DCD excitedly announced that the costume had been selected by the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) to undergo the necessary conservation treatments to help preserve the extraordinary 107-year-old artifact and to test whether it was stable enough for exhibition. At the time, Amy Bowring, then DCD’s Director of Collections and Research, had commented on the significance of the conservation treatment stating, “This project not only highlights an important Canadian cultural artifact but also signifies the importance of dance history within the shared heritage of Canadians.”

The garment and headdresses underwent an extensive two-year conservation treatment at the CCI’s Textile Laboratory from 2013 to 2015. As described in the CCI’s Annual Review 2014-2015, “The lightweight silk bodice and skirt are heavily ornamented. Use of the costume took a toll on the condition of the bodice, skirt and two headpieces. Brenna Cook, Intern, Textile Laboratory, applied a new custom-dyed silk crepeline lining to the inside of the skirt to protect the remaining original lining, to act as a separating layer between the metal embroidery, to provide a strong base for supportive stitches and to strengthen the skirt overall. The bodice was lined with a matching coloured fabric, and corrosion on the metal braid of the bodice was cleaned. Loose pearls were strung to imitate the original bodice drapery and to add accuracy to the aesthetic impact of the display. Supportive storage mounts were created for all of the costume pieces.”

Getting Ready for Exhibition – A Scientific Analysis

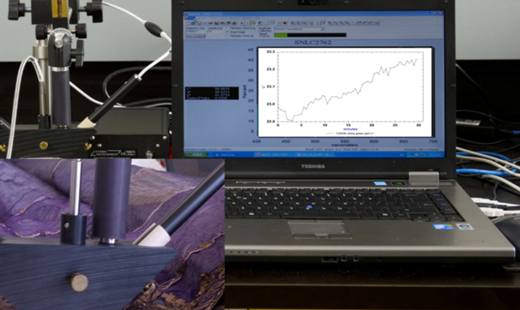

The fabric was also analyzed in order to decipher the types of dyes used and their respective lightfastness (the degree to which dyes are unchanged by exposure to light). The results of the study identified blue, green and violet dyes, which are known to have poor lightfastness or, in other words, fade easily. Accordingly, the artifact underwent microfade testing, which is a highly sensitive and almost non–destructive technique used to measure colour change during light exposure.

The dyes’ light sensitivities were categorized on a scale of low to permanent and the report recommended extreme care when displaying the costume to minimize further fading. This was very useful in exhibition planning in order to estimate the expected rate of colour loss based on lighting decisions as well as the frequency and length of the costume’s display

Only one complete costume could be submitted for treatment so DCD selected the top and bottom that Felix Cherniavsky had informed DCD went together. They were also the two pieces that required the most care. The second brassiere had very little corrosion whereas the one submitted had significant corrosion that was gradually spreading. The skirt submitted had considerable damage from darning in multiple places and spilled wax that was forcing sections of fabric to be joined in a harmful way. On further inspection and with the help of conservators at the CCI, it became clear which skirts and brassieres actually belonged together. This meant that the skirt and brassiere displayed in DCD Gallery from September 24, 2016 – April 14, 2017 were actually from two separate costumes.

interview with the conservator

Date: March 6, 2017

Location: Telephone

Interviewer: Katelyn Roughley, Curator

Interviewee: Brenna Cook, Conservator – Textiles

Question: The CCI describes the costume as undergoing “conservation treatment” as opposed to being “restored.” Can you explain the difference between the two for our visitors?

Brenna: “The life of an object is not just a single snapshot, it’s a full filmstrip, and conservation tends to try to preserve the whole filmstrip … we try to keep a whole picture of the physical evidence of the object and try not to remove things without reason or justification. The Salomé dress was a really great example of this because the skirt had quite a few layers of darning over it over the years, various types of threads, various colours, and I more or less left those alone even though I could have taken them out to make the skirt fabric look a little more cohesive. Those moments of repair are part of the whole history of the object; I kept most of them. There were a couple [of threads] that I did remove, and that’s because they were damaging the fabric in a particular way: They were too tightly stitched or they were tearing out the fabric, so I made the decision to remove them. To accomplish that, I was very careful about taking lots of photos and giving detailed explanations on what I was doing in the documentation.”

Question: What was your approach in determining how to care for the garment and/or deciding what type of conservation treatment to perform?

Brenna: “We have a framework for risk assessment called the ‘Agents of Deterioration,’ available on the CCI website, and so this informs us as to the different rates that objects are degraded over time. So, that’s a good baseline to look at. I also brought in the idea of what is this object’s role as part of a small collection, what is their storage like, they may want to do certain things with the object, so I take that all into consideration and come up with the best way to serve the preservation of the object and its future role. Realistically, the best thing for these objects is for them to go in a little tight box and never see the light of day again [laugh], but that doesn’t serve the current population, so I make a compromise and come up with a treatment which would allow for that future role of the object. And then, of course, there is specific information that comes in as well. My background, my knowledge of textiles, my historical knowledge, the testing that we did so what types of dyes were used on the skirt, what the fibres were, the physical examination of the object and picking up on areas that needed particular support … that all kind of informed the nitty-gritty of what action we decided to take.”

Question: Looking back on the project, what would you say was the most challenging aspect of the conservation treatment?

Brenna: “I think the corrosion on the bottom band of the bodice was very challenging for a couple of reasons. First, that it was there at all. Corrosion tends to build on itself over time, like, once it gets started it kind of goes and goes. We were trying to figure out why the corrosion started in the first place, because it was fairly well taken care of, you know it hadn’t been conserved, but it had been in a box, which is really great for buffering the environment, keeping things stable – it’s surprising how much good a nice acid free box can do for an object [laugh]! And so, there wasn’t really a good reason why there was corrosion there. Then I realized that she probably sweated in it [laugh]! So, a theory is that body oils and salts from her sweat impregnated the metal braid there and reacted with the metal component … [hence] the corrosion issue, which of course, just weakens the structure of the braid and is visually distracting. So, that was really challenging. I spent a lot of time reading up on treatment of metal threads and the conclusion I came to was that there isn’t a lot we could do about it … So, what I ended up doing what just cleaning it. I decided that the best thing to do was to remove those oils and salts with the hopes that it would reduce the amount of corrosion that would be created, assuming we could keep it in a reasonably good environment going forward.”

Question: Do you have any tips for museum professionals in terms of caring for or handling textiles, especially for those smaller institutions that may not have a permanent conservator on their staff?

Brenna: “I think that the best thing that smaller museums can do is look to preventative conservation aspects, so there are things like keeping the area clean, keeping things boxed and as supportive as much as they can, training people on how to handle textiles. It seems like the biggest risk that textiles face, I find, in institutions of any size, is the handling. When an object comes in for processing it gets touched quite a bit by different people, so all these people need to know how to handle objects safely and effectively – that would help a lot. That’s also something that doesn’t cost a lot of money since there are free resources online that museums can use to train their staff; that would be an effective thing … Things to keep in mind are cleanliness, so if you don’t have gloves wash your hands pretty thoroughly, if you do have gloves and they’re cotton gloves, wash them periodically [laugh] or use disposable nitrile gloves. And, also, keep your work area clear. On a table, ensure you have enough space for you to work and maybe put down some clean tissue paper to help reduce handling since sometimes it’s easier to just slide an object around on tissue rather than pick it up and move it. And, general awareness that these are not just clothes … historic textiles are different, we need to create an awareness that these are delicate and we can’t treat them like we would probably treat everyday textiles that are around us.”

*Note: Hyperlinks provided by interviewer, not suggested by interviewee.