Presents

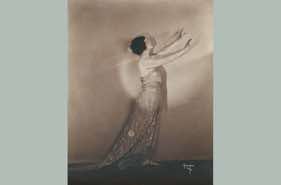

Maud Allan - An Edwardian Sensation

Falling Into Obscurity

fighting to stay in the limelight

Even before Maud Allan’s darkest secret was exposed, the “Salomania” craze had started to wane. She became preoccupied with a new project to replace The Vision of Salomé. During February 1911, she began developing a new “Orient” ballet called Khamma that she planned to debut in 1916 during her North American tour. The ballet was to be accompanied by an original score commissioned from Claude Debussy who undertook the contract purely for its generous compensation. For unknown reasons, Allan never performed the work. At the last moment, she pulled the piece from her repertoire and replaced it with Nair the Slave, which was dismissed by American critics as a sloppy imitation of Scheherazade by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

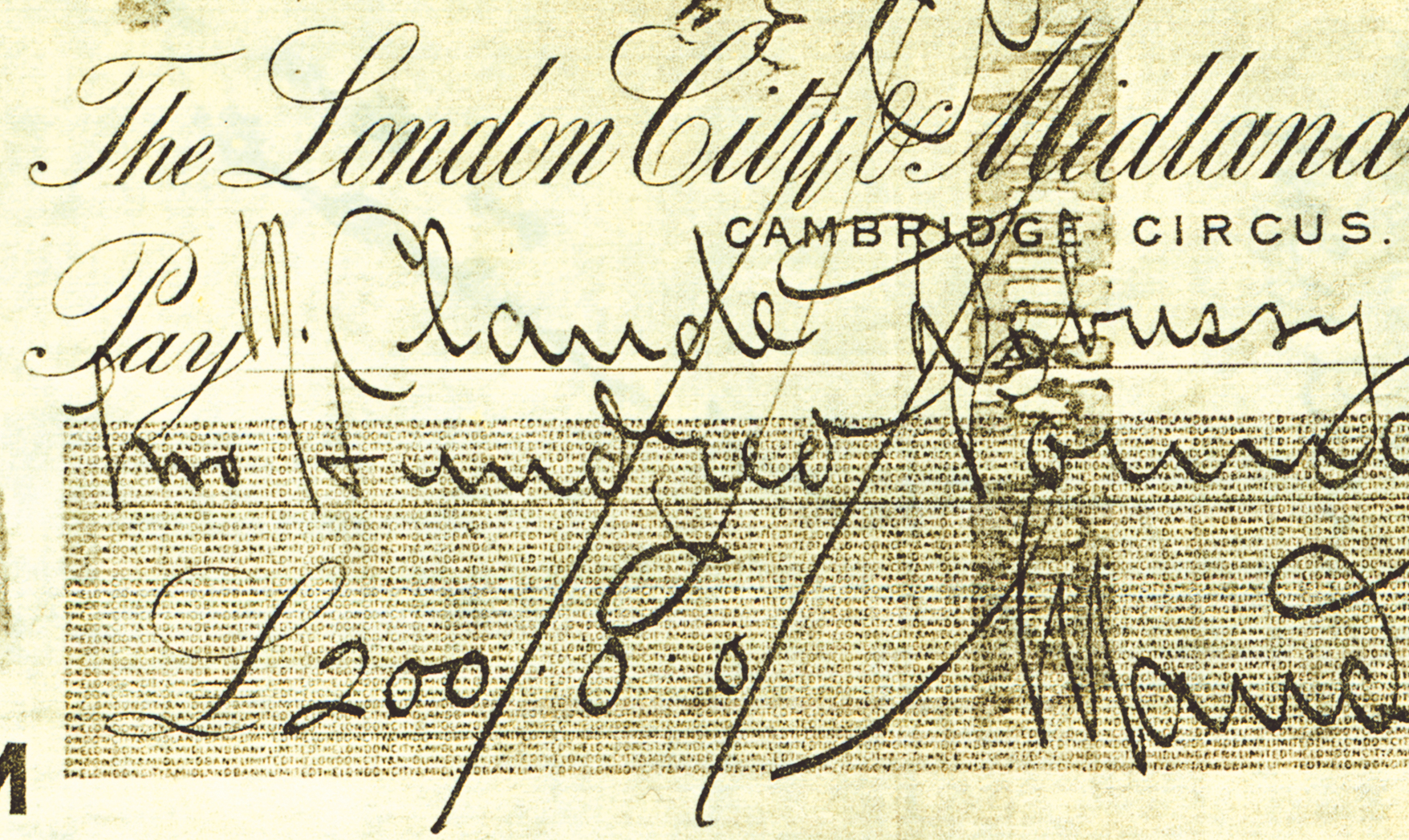

Under the terms of their contract, Allan was to pay Debussy 20,000 francs plus royalties. This project turned into a costly and frustrating blunder for Allan as well as a burden for Debussy. In their personal letters, Allan incessantly complained, “As the music stands, it could never be a success,” while Debussy grumbled how that the “détestable Maud Allan” bombarded him with insatiable demands. Allan never performed the work. It was given its first orchestral performance in 1924 and was finally staged at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on March 26, 1947.

While the original manuscript for Khamma was never found, a ragged envelope containing an incomplete manuscript version of the piano sketch, prepared by Debussy’s amanuensis, Charles Koechlin, was unearthed after Maud’s death. The libretto, written by Allan, reveals the story of the Egyptian dancer Khamma who sacrifices herself to the god Amun-ra in order to save her people from seige and war.

Maud joined the Cherniavsky Trio a year later for a fifteen-month tour of India, the Far East, and Australasia to keep her dancing career afloat. Violinist Leo Cherniavsky, seventeen years her junior, became one of Maud's many romantic conquests. Leo was not her first romantic liaison. The provocative dancer had a history of manipulating men for financial gain, and once again saw an opportunity to use her renowned sexual appeal to advance her career. Her steamy love affair only lasted a few years until Maud betrayed Leo’s trust by tricking him into signing a new contract that reduced the Trio’s profits by 75 percent. She deceived Leo by saying that her manager, Alfred Butt, had “professionally” prepared a new contract, with the only changes being more formal wording. After signing the contract, the Trio learned that Maud was now entitled to three quarters of the group’s profits.

After Maud’s dancing fame began to wane, she seems to have been in the process of pursuing an acting career. She had been in conversation with English actor Laurence Irving about joining a project upon his return from a North American engagement, but he died in 1914 after boarding the SS Empress of Ireland en route to Canada, where the ship struck a coal freighter and sank within minutes. A year later, in 1915, she moved back to California for about a year where she appeared in the silent film The Rugmaker’s Daughter, which featured segments of her dancing.

In the early 20th century, felt pennants were used to promote films, but it was a trend that only lasted a few years. Hollywood used pieces of felt cut in the shape of a flag, with lettering applied either by paint, embroidery, or by cutting out letters from different colors of felt, gluing them to the pennants, and then machine stitching the edges. The August 25, 1915 Moving Picture World noted the popularity of pennants in a story titled “Pennant Craze Strikes City,” describing the popularity of pennants at San Francisco’s World Exposition that year. Pennant collecting reached its height in 1917, with several companies listing pennants for sale in magazines, but by 1920, the craze was over.

Three years following her acting debut, and after the costly blunder with Khamma, Maud Allan was back in London where it was announced that she had accepted the lead role in a private production of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé (the play was still banned from public performance). Unfortunately, this dalliance with the theatre would lead to the notorious Black Book libel case and Allan’s ultimate downfall.

Within a week of the advertisement announcing Allan’s casting in Wilde’s play, an article boldly titled, “The Cult of the Clitoris” appeared in The Vigilante, a newspaper MP Noel Pemberton Billing used to propagate his homophobic views that Germany was a degenerate country filled with homosexuals aiming to lure Britain’s citizens into corruption. Billing had claimed in a prior issue that the Germans had a “Black Book” containing the names of 47,000 male and female British citizens who were susceptible to blackmail due to their “sexual peculiarities”. Among the names implicated were former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and his wife Margot. The article implied that Maud Allan was a lesbian and a German sympathiser and it also suggested that audience members planning to attend her upcoming performance were likely among the names in the Black Book.

When Allan sued for criminal libel, she became a pawn in Billing’s plan to advance his personal biases. The bizarre trial was drawn out over five days and proved to slander Allan’s reputation even further. Billing accused her of everything from illicit sex to being a “lewd, unchaste, and immoral woman,” culminating with Allan being forced to admit under oath that she was the sister of murderer Theo Durrant. Allan’s association with a murderous sibling was enough for the jury to agree with Billing’s assessment and he was acquitted of the charge, while Allan was shunned by the public and advised by her managers not to appear on any London stage.

Maud Allan attempted to rekindle the magic with her audience at performances in the United States in the 1920s and the 1930s, giving her final performance in California in 1936. Correspondence from 1939 indicates her address was still at Holford House in London, but she eventually settled in Los Angeles during the Second World War and worked as a draughtswoman at McDonnell Aircraft. In a letter dated April 1949, Maud described her fall into obscurity as a stately decline “from affluence and a beautiful home to a small ugly room without proper conveniences.” Maud Allan died in Los Angeles in 1956 … penniless and forgotten.