| |||||||

![]()

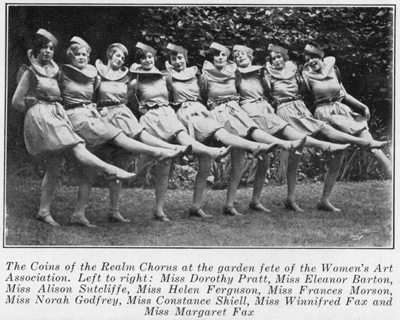

In a meeting on April 11, 1939, Sutcliffe was elected to the executive of the Allied Arts Council. This advocacy work is not a surprise from Sutcliffe - passionate and fearless, art was of paramount importance in her life and she stood up for what she believed in. And so, in addition to articles and speeches, the art work continued. In the spring of 1939, Sutcliffe staged the "Goddess of Spring" as part of the 19th National Flower and Garden Show's pageant. The elaborate pageant included a number of school, women's and theatrical groups representing different flowers. For example, the Kildonan Girls' Club were the violets, the Women's Catholic League were daffodils, the Women's Advertising Club were daisies; the Shakespeare Society represented the larkspurs and the Toronto Masquers (Sterndale Bennett's theatrical group) were carnations. There was also no lack of pomp at this pageant as the wives of various public figures, such as Ontario Premier Mitchell Hepburn and Lieutenant-Governor Albert Matthews, were presented with a variety of corsages by the flower show's participants. Spring also brought recital time and Sutcliffe presented her Toronto Conservatory of Music pupils in a demonstration at Hart House Theatre on May 20.

Sutcliffe's classes at the Conservatory began again in September; receipts for room and board indicate that she spent part of the summer in New York. Talk of another world war probably disuaded even the adventurous Sutcliffe from overseas travel. It seems that the work of her beloved German teacher Kurt Jooss may have made its way to Canada for Christmas of 1939. A letter from September 1939 indicated that Marjorie Haskins of the Norma Coulson School of Dancing in Galt, Ontario (near Guelph in Southwestern Ontario), was arranging for Marlise Bok, a teacher with Jooss at Dartington Hall, to give an intensive twelve-day course over the Christmas holidays. With World War II well underway by Christmas of 1939, it's difficult to know whether or not Bok made the trip overseas.

While the effects of the war do not have an overwhelming presence in Sutcliffe's archival collection, there are signs of the times dotting documents from the 1940s. Anti-semitism is revealed in a letter from the Perry-Mansfield School of the Theatre. Founded in 1913 by Charlotte Perry and Portia Mansfield, the school was based in the U.S. Mansfield sent a letter and promotional materials to Sutcliffe in which she outlines the commission system in place; teachers who sent their students to the Perry-Mansfield summer camp were given a commission based on the tuition paid by the student. A notice that outlines the various types of commissions clearly states, "No commission is given on Jewish girls." Another piece of correspondence from April 1940 thanks Sutcliffe for her performance at the "canteen" to entertain the troops; the letter is signed by Sydney Mulqueen, chair of the entertainment committee, who would further contribute to Canadian ballet history by being one part of the triumvirate that brought Celia Franca to Canada as the founding artistic director of The National Ballet of Canada.

In the spring of 1940, Sutcliffe presented her version of The Nutcracker as part of her year-end student recital. The entire production received rave reviews from critic Augustus Bridle who wrote, "Every so often Toronto Conservatory presents a program that expresses the joy of living more than the ecstasy of learning. With Alison Sutcliffe in charge of the dance department of rhythmics, such things are inevitable." Prior to the intermission, there was a quartet titled Bathing followed by a solo Waltz danced by Barbara Davis (later known as Barbara Chilcott), as well as a lively version of Humpty Dumpty. The Nutcracker provided a colourful extravaganza that included the Russian Dance, Oriental Dance and the Dance of the Flowers and, of course, a solo by the Sugar Plum Fairy. Costumes were designed by Sutcliffe's future sister-in-law, Erma Lennox.

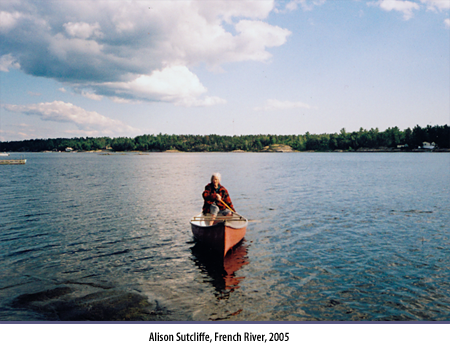

Having escaped to French River for the summer of 1940, Sutcliffe had to turn down a request from Toronto Daily Star music and drama critic Augustus Bridle. He was coordinating two large programs for the Canadian National Exhibition that August and needed Sutcliffe to stage a five-minute Old English Country Dance using eight dancers. This project may have been an off-shoot of the plans that had been proposed by the Allied Arts Council in the winter of 1939 in which it was suggested that the work of local artists should be shown at the Exhibition. Bridle wrote again on September 17, 1940 to tell Sutcliffe of plans to "repeat the Coliseum Chorus Festival" in October at Maple Leaf Gardens with proceeds going to four War Funds. Bridle also laid out plans to expand the program and wished to incorporate a mazurka set to the chorus of Edward Elgar's Bavarian Highlands Dance. In the end, Sutcliffe was not able to participate in the expanded version either due to a scheduling conflict; however, in an October 3, 1940 article by Bridle in the Toronto Daily Star he mentions that Sutcliffe had been asked to stage both dances.

Another interesting letter arrived at the Sutcliffe cottage in French River around August 7. This one was from Sutcliffe's long-time pupil Barbara (Davis) Chilcott who was writing from the Summer Drama Workshop she attended in Mt. Kisko, New York. Chilcott writes:

What can I say? I don't want to make you feel any worse than you do now, but I do want you to know that I feel just as badly as you do. I'm really dreadfully sorry Alison dear! What prompted you to give up your teaching? It's none of my business I know so don't answer that if you don't want to. I shall miss your instruction and friendly advice so very much.

Around August 29, Sutcliffe received another letter from a family friend, Lila Halditch, who makes reference to Sutcliffe's taking a year off from teaching. Then, a letter was sent by Florence Somers, Director of the Margaret Eaton School, on September 19, 1940, asking Sutcliffe to fill a one-year position replacing teacher Marion Hobday Allen (another name that appears frequently in theatre and dance playbills of the 1930s). Sutcliffe was asked to teach "Modern Dancing" and she immediately sketched out a letter to Somers stating that she would like to meet with her. What exactly happened is unclear at this point. A letter to Sutcliffe from Hobday Allen dated September 16, 1940 indicates that she was suffering from ulcers, which is why she wasn't teaching that season. Whether Sutcliffe took over Hobday Allen's classes is not known, nor are her reasons for leaving the Toronto Conservatory of Music.

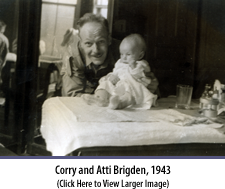

Sutcliffe married art teacher Corry Brigden (1912-1979) in December 1940 and the couple soon moved to Hamilton. While her performing career seems to have come to a close, or at least slowed down, after leaving Toronto, Sutcliffe continued to teach in her own studio and visited Toronto frequently to see performances. She and Brigden raised three children together -- Atti (1942-2002), Elsa (1947-) and William (1949-) -- and when Brigden retired, the couple often spent part of the winter in Mexico. Here, Sutcliffe became interested in photography and filmmaking and explored these art forms with the focus and curiosity that had flamed her work in dance. After her husband passed away, she continued to travel to Mexico driving down in her Dodge van that she had outfitted for camping - she stopped driving there when she was 85 and instead flew down annually until she was 90. She was always fascinated by reflexology and alternative medicines and continues to explore these areas at the age of 99. Sutcliffe's youngest daughter, Elsa, says of her mother, "Alison did a lot and was not afraid to try something new and always mixed with people of all kinds wherever she was. She always found something to enjoy in everyone and has a great memory for people."

Sutcliffe married art teacher Corry Brigden (1912-1979) in December 1940 and the couple soon moved to Hamilton. While her performing career seems to have come to a close, or at least slowed down, after leaving Toronto, Sutcliffe continued to teach in her own studio and visited Toronto frequently to see performances. She and Brigden raised three children together -- Atti (1942-2002), Elsa (1947-) and William (1949-) -- and when Brigden retired, the couple often spent part of the winter in Mexico. Here, Sutcliffe became interested in photography and filmmaking and explored these art forms with the focus and curiosity that had flamed her work in dance. After her husband passed away, she continued to travel to Mexico driving down in her Dodge van that she had outfitted for camping - she stopped driving there when she was 85 and instead flew down annually until she was 90. She was always fascinated by reflexology and alternative medicines and continues to explore these areas at the age of 99. Sutcliffe's youngest daughter, Elsa, says of her mother, "Alison did a lot and was not afraid to try something new and always mixed with people of all kinds wherever she was. She always found something to enjoy in everyone and has a great memory for people."

Like so many of her colleagues from the 1930s, Alison Sutcliffe has been largely lost to history. Her archival collection has brought to life the theatrical richness of a period that was overshadowed by the Great Depression. And yet, when we study Sutcliffe's life and career and see the activity of Toronto's music, dance and theatre artists, it is clear that they persevered in a difficult time and enriched the lives of Torontonians. These artists were busy staging shows, educating audiences and training new performers and they laid the foundation for the next generation of artists to continue to build Canada's performing arts scene.

![]()

©2008, Dance Collection Danse

Alison Sutcliffe Exhibition Curator: Amy Bowring

Web Design: Believe It Design Works

Mexico, 1960s

Costumes sketches by Erma Lennox

Alison Brigden, 1940s