| |||||||

When Alison Sutcliffe began studying dance in the early 1920s, Toronto was hardly devoid of teachers. Dance historian Mary Jane Warner has identified several teachers who had been established since the turn of the century including Amy Sternberg who taught ballet, ballroom, aesthetic and national dancing; Elsie and Albert Davis who took over the ballroom dancing school their father, John Freeman Davis, had started; and Charles Freeman Davis, another son of John Freeman Davis, who also taught ballroom dancing. A decade into the new century, other teachers appeared such as Samuel Titchener-Smith who had studied ballet at the Vestoff-Serova School in New York, and sisters Fanny and Helen Birdsall who taught ballet, tap, acrobatic and jazz. After the Russian Revolution, ballet dancers fleeing Bolshevik rule began appearing in Toronto including Leon Leonidoff who taught ballet with his partner Florence Rogge and also staged productions at the Hippodrome and Uptown Theatres, among others. Dimitri Vladimiroff was another Russian who arrived in Canada after the Revolution; he produced several benefit concerts in addition to his teaching work. Another Russian expatriate who was a contemporary of Sutcliffe's was Boris Volkoff. He arrived in Toronto in 1929 after working in Asia and the United States. He took over for Leon Leonidoff at the Uptown Theatre, eventually opened his own school and created the Volkoff Canadian Ballet. He is known as the Father of Canadian Ballet for his contribution to dance in the mid-twentieth century.

When Alison Sutcliffe began studying dance in the early 1920s, Toronto was hardly devoid of teachers. Dance historian Mary Jane Warner has identified several teachers who had been established since the turn of the century including Amy Sternberg who taught ballet, ballroom, aesthetic and national dancing; Elsie and Albert Davis who took over the ballroom dancing school their father, John Freeman Davis, had started; and Charles Freeman Davis, another son of John Freeman Davis, who also taught ballroom dancing. A decade into the new century, other teachers appeared such as Samuel Titchener-Smith who had studied ballet at the Vestoff-Serova School in New York, and sisters Fanny and Helen Birdsall who taught ballet, tap, acrobatic and jazz. After the Russian Revolution, ballet dancers fleeing Bolshevik rule began appearing in Toronto including Leon Leonidoff who taught ballet with his partner Florence Rogge and also staged productions at the Hippodrome and Uptown Theatres, among others. Dimitri Vladimiroff was another Russian who arrived in Canada after the Revolution; he produced several benefit concerts in addition to his teaching work. Another Russian expatriate who was a contemporary of Sutcliffe's was Boris Volkoff. He arrived in Toronto in 1929 after working in Asia and the United States. He took over for Leon Leonidoff at the Uptown Theatre, eventually opened his own school and created the Volkoff Canadian Ballet. He is known as the Father of Canadian Ballet for his contribution to dance in the mid-twentieth century.

The vaudeville stage and floor shows in night clubs and hotels provided a professional dance scene and potential work for local dancers; however, most other dance performances took the form of school recitals and benefit concerts, or shows by touring dance companies. Ballet had become much more popular after the visits of Anna Pavlowa (at least ten appearances in Toronto between 1910 and 1924), but ballet was still gaining a foothold among local teachers who needed to travel to England or the United States, or take correspondence courses to learn the technique. Teachers such as Sternberg and Titchener-Smith did not initially teach ballet but made a point of learning and teaching the form after Pavlowa's success with Toronto audiences. Without television or a resident professional ballet company, and with only amateur opera performances or those of touring companies, paying work for dancers was generally limited to vaudeville and night clubs in Toronto in the 1920s.

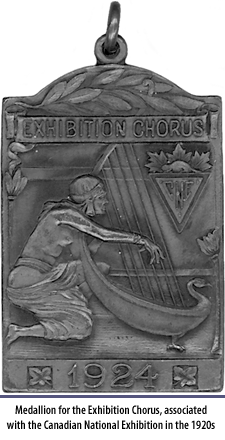

The emerging Toronto dance milieu was not alone, however. Both the music and theatre communities of the 1920s were far from well established professionally, though there was a busy amateur scene in all of the performing arts. According to music historians Helmut Kallman, Carl Morey and Patricia Wardrop, the situation for musicians echoed that of dancers; it was vaudeville that offered regular employment for musicians accompanying silent films and other acts, for example, Luigi Romanelli's orchestra performed regularly at the Tivoli movie house in downtown Toronto. When talking movies gained popularity in the 1930s, the need for orchestral musicians in the theatres diminished, but radio broadcasting supplied musicians with new opportunities. One group that took advantage of radio was Luigi von Kunits' New Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1923 and renamed the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 1927, which began a transcontinental radio series in 1929. Other symphony orchestras of the time include those associated with the Toronto Conservatory of Music and the University of Toronto. The city was home to a number of choral and chamber groups in the 1920s including the Orpheus Society, the Exhibition Chorus associated with the Canadian National Exhibition, the Hart House String Quartet and the Five Piano Ensemble, among others. While visits were made by touring opera companies, attempts to establish a permanent resident company in the city were unsuccessful at this time.

The emerging Toronto dance milieu was not alone, however. Both the music and theatre communities of the 1920s were far from well established professionally, though there was a busy amateur scene in all of the performing arts. According to music historians Helmut Kallman, Carl Morey and Patricia Wardrop, the situation for musicians echoed that of dancers; it was vaudeville that offered regular employment for musicians accompanying silent films and other acts, for example, Luigi Romanelli's orchestra performed regularly at the Tivoli movie house in downtown Toronto. When talking movies gained popularity in the 1930s, the need for orchestral musicians in the theatres diminished, but radio broadcasting supplied musicians with new opportunities. One group that took advantage of radio was Luigi von Kunits' New Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1923 and renamed the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 1927, which began a transcontinental radio series in 1929. Other symphony orchestras of the time include those associated with the Toronto Conservatory of Music and the University of Toronto. The city was home to a number of choral and chamber groups in the 1920s including the Orpheus Society, the Exhibition Chorus associated with the Canadian National Exhibition, the Hart House String Quartet and the Five Piano Ensemble, among others. While visits were made by touring opera companies, attempts to establish a permanent resident company in the city were unsuccessful at this time.

For dramatists, the vaudeville theatres and the legitimate theatres, such as the Royal Alexandra, provided professional opportunities for actors; however, the majority of acts or productions were foreign. The legit theatres provided Torontonians with mainly British or American plays performed by resident stock companies and the vaudeville theatres usually consisted of acts from the United States that toured a circuit of theatres owned by businesses such as Shea's, Pantages or Loew's; these productions provided paying work for some home-grown performers, but not many. According to theatre historian Robert B. Scott, one resident company that did make a point of headlining Canadian talent was Vaughan Glaser's group at the Uptown Theatre, which opened in 1921. Another was the Cameron Matthews Players beginning in 1923; Matthews is responsible for introducting Jane Aldworth (later Mallett) to Toronto audiences and he also featured Charles Fletcher, who had acted for Glaser as well. But the life of stock companies was competitive and tenuous and with the rise in popularity of talking movies and radio in the 1930s, managers like Glaser and Matthews either moved to the U.S. or failed to establish permanent theatre companies. For local actors, directors and playwrights, the amateur scene was where the real activity lay.

Historians Martha Mann and Rex Southgate report in their article on amateur theatre in the anthology Later Stages that drama played a part in the activities of many Toronto clubs, associations, churches and schools in the 1920s. For example, St. Andrew's Church had its St. Andrew's Players, members of the Heliconian Club and the Women's Press Club also presented plays, and schools frequently had drama groups such as Northern Vocational School's Norvoc Players under the direction of teacher and playwright W.S. Milne. Two very active amateur groups in Toronto in the 1920s were the Arts and Letters Players from the Arts and Letters Club (founded in 1908) and Hart House Theatre (founded in 1919). The Arts and Letters Players performed on a stage in their Elizabethan-styled great hall presenting an annual spring revue, Canadian plays by writers such as Bertram Brooker, and also numerous plays that had never been performed in Canada. Hart House Theatre was definitely a model for the little theatre movement, which expanded across Canada in the 1930s spurred by the creation of the Dominion Drama Festival in 1933. A Hart House brochure from 1928 explains that the building itself was a social and recreational facility for male undergraduates and was given to the University of Toronto by the Massey family. The Hart House Theatre was actually an afterthought and was built in the sub-basement under the quadrangle; the concrete arches that support the quadrangle also create the roof of the theatre. The theatre seats 450 people and when it was built, its technical equipment made it one of the most advanced theatres in North America. During the pre-World War II era, some of the actors, writers and visual artists involved in productions at Hart House include Raymond Massey, Lloyd Bochner, Dora Mavor Moore, Lorna (McLean) Sheard, Lawren Harris, Arthur Lismer and Merrill Denison.

![]()

©2008, Dance Collection Danse

Alison Sutcliffe Exhibition Curator: Amy Bowring

Web Design: Believe It Design Works

Advertisements reveal some of the teachers in Toronto in 1934