| |||||||||

| |||||||||

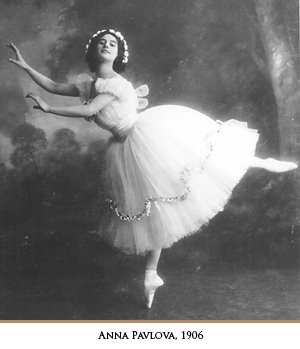

It's only after 47 lines of breathless introduction that Makovski gets to the opening ballet, The Arabian Nights, recounting the tale of the “barbarians,” the slave, Azyiade (Pavlova) and the desert chieftain (Mordkin). A short paragraph shows the reviewer recovering from the experience: It is over. The curtain is down and the audience suddenly awakes and roars its applause. But feebly have we grasped the art, the wonder of that dancing, but we have drunk a nectar of which we have never tasted heretofore, and now are wild for more. The curtain rises on the corps de ballet in Polish costumes, and then Pavlova and Mordkin perform a pas de deux. This is a marvellous exhibition of technique. She spins like a top, she sways back and forth in his arms. The music is slow, each step of the dance calls for perfect execution. But more than mere technique is the extraordinary expression, the wonderful interpretation of the music. Mordkin does “a wonderful pas seul” before Pavlova appears in her most famous role: Then Pavlowa in a most beautiful exquisite little pas seul called “The Swan.” The lights are low and she floats across the stage as if she were suspended in the air. Finally she dies, her pinions fluttering and broken as she sinks to the ground, and the applause breaks out more strenuously than ever. The grand valse from Raymonda, a pas de deux to the music of Rubinstein's Valse Caprice, some dances to Liszt “and then the climax,” Pavlova and Mordkin in Bacchanale to the Autumn movement from Glazunov's The Seasons, which “drives the audience into such an outburst of enthusiasm as has never been heard in the Opera House before.” Afterwards, following many curtain calls, “we rise from our seats to stand and recover somewhat from our bewilderment as the strains of 'God Save the King' bring us back from the world of unreality in which we have lived for an evening.” There's more: with reckless disregard for a newspaper's space restrictions, two final paragraphs are used to sum the evening up. It is all over. The lights are out and Mordkin, Pavlowa and the Russian Imperial ballet are far away. They have come and gone. They have given us something of which we shall dream all our lives. Their art is indescribable. It stands for something higher and more beautiful than words can picture. It is a “passionate emotion” but it is wholly good and rouses the purest and best feelings of which man is capable. Mlle. Anna Pavlowa, Danseuse Etoile, and M. Mikail Mordkin, Premier Danseur Classique, farewell! Our best thanks to those that brought you, and our highest respect and devotion for your art (Province, Nov. 18, 1910). The review, typical of newspaper reporting, is frustrating for its lack of detail. Nonetheless, the absolute abandonment of the writer to the ballet at hand is an inspiration. (next page) ©2006, Dance Collection Danse | ||