|

|

| |||

|

previous page l enter dancing home |

|

|

Ancestral Calling

A few years ago I went to the Blacks in Dance conference in the U.S. There was a huge dance jamboree at midnight – it was in the hotel, on the ballroom floor. Someone at dinner asked if I was going to take it in – I said, “No, at my age I am not dancing on a cement floor.” The table went quiet – I didn't notice, but someone said – “What do you mean, at your age?” I started paying attention and then noticed, in the concert, all the people dancing were boys, they were little boys. There were no older men dancing – all the companies had these twenty-two-year-old dancers. It's still like that in the U.S. – companies have very young dancers; if you're over thirty, that's it. It's all about technique and how high the jumps can go. Earlier at the conference, I had performed my solo in Sand – the piece ended and for about thirty seconds there was a stunned silence. I thought, “Oh God, they didn't like it.” Then the applause started. They are not used to seeing anyone over thirty on stage and didn't know what to do with maturity. It's a shame – there are so many great older dancers, and there's no outlet for their talent.

I recognized the focus on youth and virtuosity fairly early, and the competition turned me off. Sasha Ivanochko had just graduated from STDT. She was taking class at Ailey, and we went together. Kazuko Hirabayashi was teaching class – Sasha and Megan (another girl from STDT) and I were there … going across the floor in a long and complicated combination that ended in a tilt. At STDT you were expected to know the music and the combination, so that was what we knew. The other people in class with us, all they saw was the tilt at the end – the stuff in between didn't matter. Kazuko stopped the class after us and said, “Did you see that? That's what dancing should look like.” I thought, “Oh Lord have mercy, now they're going to hate us.” For a year, that's what my life was like. After class, teachers would say, “You must not be American.” I knew I could not go through my entire dance life in such an overtly competitive atmosphere – no one paid attention to the music or the content of the material, only to their own performance, and to the physicality.

Tita Evidente [TDT accompanist] got me a job with Jubilation Dance Company in New York right after I graduated from the School of Toronto Dance Theatre. It was an experience, working in a different environment. It was a six-month contract. The work was good, very hardcore, but it was insane – choreographers would come and no one would pay attention. I'd think, “This could be an easy process – just pay attention, you'll get it and then we can go home.” The perfect Canadian contemporary dancer – that was me. Other dancers added extra stuff, extra angst, whatever. Teachers and choreographers were amazed at how I calmly just did everything.

New York City was not the place I wanted to dance. When I go back there, I enjoy the buzz, but I'm always happy to say, “Thank you very much,” and go.

CA: You were a member of Danny Grossman's company for a long stretch. Can you speak about your experiences a bit?

BL: Cast in Curious Schools of Theatrical Dancing, I was terrified. In an artistic meeting, Danny Grossman announced a season of all solos. I had seen Randy [Glynn] do it, and Bohdan Romaniw. It seemed like a very brutal piece. I said, “Are you sure? I'm not that kind of dancer.” Eddie [Kastrau] was great – he coached me, and we worked on it for a long time. Three weeks before our premiere, Danny came in; everyone was running their piece. I performed the solo. Danny just got up and started talking to someone. It was horrible. Andrea Nann came to me after and said it was the first time she could actually watch the whole piece. It was always too violent, she said, when other people danced it. I'd brought a passion and a humbleness to it, and she'd just sat there mesmerized. That's when I got the confidence. It was difficult. I never did get corrections from Danny – and I danced the piece all over the world.

Danny's company – I was there from 2002 to 2008 – it was a great time. It really pushed me artistically, because a lot of the work I did with Danny was not what my body would naturally do. A Simple Melody [choreography by Peter Randazzo, restaged by DGDC] was the only piece I ever did with that company that was anywhere near what my training was. Peter came in to cast it and I discovered I was doing the Pavane; casting was always surprising.

Danny's company – I was there from 2002 to 2008 – it was a great time. It really pushed me artistically, because a lot of the work I did with Danny was not what my body would naturally do. A Simple Melody [choreography by Peter Randazzo, restaged by DGDC] was the only piece I ever did with that company that was anywhere near what my training was. Peter came in to cast it and I discovered I was doing the Pavane; casting was always surprising.

CA: You're about to leave for Trinidad. What do you want to share there?

BL: I'm going home to perform in and help organize fiftieth anniversary celebrations of Les Enfants – after that, Joyce says that's it, she's had enough. When I go home, they always want me to teach. What I'd really love to do most is sit down and talk with dancers so I can share some of the ideas and the visions and experiences that I have had. They are still walking this tightrope of “I'm a dancer, I perform and choreograph.” I want to say, “You can be other things; you can be way more, and be a lot more self-sufficient if you think in a different way about who you are as a dancer.” The culture of the islands breeds that kind of thinking, and it's frustrating. Even the way they build studios – always with four walls. With tropical weather 24/7, why have studios with four walls? An open wall could be converted to a theatre quite easily. They say, “No, you have to have a space with bleachers.” And I say, “No, it's the same concept.” I'd like dialogue … I'm hoping to go and start a series myself and get them going. They'll come to class, but it's hard to get them to come out to discuss.

There's also a huge generation gap between the elders and the young dancers. People of the generation in between – a lot of us have left. There's a huge gap – there are a lot of people dancing now I don't know, and they don't know who I am. There's a lot of friction too. Younger people who are dancing don't know the history, they see elders as old and archaic, and they don't understand the value of what they can get from them because they don't have that transition of people from the generation between. There are a lot of issues. The elders are dying out – every time I'm back I learn someone else has passed. Young dancers need to talk to these people. And they need to understand – if a person is eighty-two years old, they are not going to change. So you have to go to them; you have to listen and accept whatever they give you. They are not going to change because you might think something should be different. If they're grumpy, let it go. If they repeat something fifty times, listen. They are not going to change. It's a very different generation.

I try to go back as often as I can. I remember when I was a young dancer how exciting it was to have teachers come to Trinidad. When I go on vacation I always throw some dance clothes in my bag, and though I insist that I won't teach, I always end up teaching at least one class.

When I do a doctorate, I want to look at Africentric education – how African tradition uses the arts, how that has a major impact in education. Teaching public school was supposed to be my segue – but it's been two years of not what I'd hoped. [BL teaches at the Africentric school in Toronto]. It's a Toronto District School Board model and a difficult fit for some of the ideas I want to explore – so I may have to do it in tandem, and do it separately.

I may do a doctorate in Toronto, because of geography – or perhaps somewhere more exciting. Sussex – they want me to be there for a year, and to teach. I say, I can't be there for a full year, I'll do summer … If I had the time, I'd be there no problem – there's just so much going on here. But it will happen. It will.

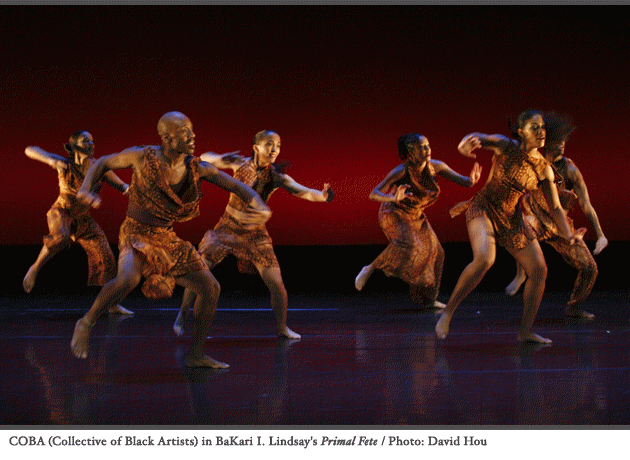

COBA moved to Daniels Spectrum in Toronto's Riverdale in the summer of 2012. Learn more about the company at cobainc.com.