|

next page l previous page  CA: What was your dance background when you came to Canada? What did you embody – what did you bring with you? CA: What was your dance background when you came to Canada? What did you embody – what did you bring with you?

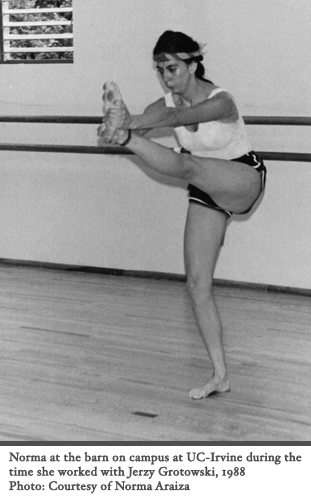

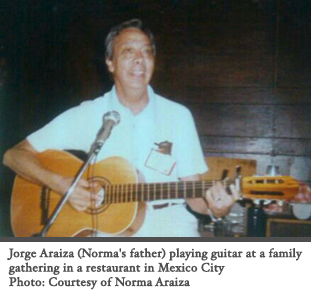

NA: Mainly, I brought what I was practicing professionally at the Laboratory of Performing Arts at the National University in Mexico. This was research –trying to get back to the origins, getting back to when the arts were together; when dance and theatre and music and poetry were not separate – this goes very much with the indigenous way. That was my practice. I learned physical theatre and theatre anthropology directly from Grotowski – I worked with him for two years. CA: When you lived in Poland?NA: No. Actually, I went to California to study with him. But Mexico was one of his favourite places, so he would go to Mexico a lot. As well as Eugenio Barba – I also learned from him. Through the National University in Mexico City we were able to go to Irvine, California, to work with Grotowski at the university there. And then, every time we were in our lab, we would video rehearsals and send our work to him in Italy. He would get back to us with feedback. We were working long distance, and then we would meet with him for further work in the US. It was one of the best periods of time for me in terms of my profession.I started formal dance training very late, yet started dancing at a very young age. My dad was a musician and composer, and my mom is a fantastic dancer – she's seventy-nine and still ballroom dances. I grew up in a family that was, informally, very much into the arts. My uncles, aunties, everyone, would get together and sing and play music and fool around. That's how I grew up. I always liked different styles of dance, so I learned ballroom, Hawaiian, Tahitian dance. I learned folk dances of Mexico and traditional dances – all kinds of dances. I took classes here and there – never formally, until my first year of university, when I discovered modern dance. I was about twenty – I thought it was the most amazing thing ever! CA: That's often the way …NA: I was going to be an athlete, not a dancer – I was very much into sports, I was competing nationally; I was actually preparing to go to the Pan-American Games. CA: What was your sport? NA: Running and jumping. I have long legs, and I was good at it. But my dad said, “You have to study for a career. You're not in the USSR, you can't make a living as an athlete in Mexico.” So I had to study – which I'm grateful for – but then I stopped doing sports. Then I discovered modern dance … NA: Running and jumping. I have long legs, and I was good at it. But my dad said, “You have to study for a career. You're not in the USSR, you can't make a living as an athlete in Mexico.” So I had to study – which I'm grateful for – but then I stopped doing sports. Then I discovered modern dance …

CA: What form or style was it – Graham?NA: Yes, Graham – and Limón. Both. There were a few companies in Mexico that were developing their own style. First of all, a close friend said, “I'm taking modern dance. Do you want to come with me to classes?” I said, “What is that?” “Just come.” She said. My first teacher, an American woman who had been living in Mexico for many years, told me that my legs were very long, but it was too late for me to start dancing. She really discouraged me. She said, “Don't even try.”CA: That's terrible! NA: Absolutely. So I always thought, “Okay, I'll just take classes, because I love it,” but never thought of becoming a professional dancer. I loved it so much I continued taking classes. I took ballet classes infrequently; mostly I studied different styles of contemporary dance. And I resisted when told that I'd never be a dancer. There was a Mexican contemporary company called Alternativa – I guess in English it would be Alternative Contemporary Dance. The director was much criticized because he had dancers of all kinds and sizes – tall people, short people, chubby people – all kinds and levels. He was an amazing person – he accepted me to take classes, and then said, “I'd like you to be part of the company.” That's how I came to be part of a professional contemporary dance company in 1986. I was there until the company dissolved, and then I went into the Laboratory of Performing Arts.  When I got immersed in physical theatre I knew I could incorporate dance. I studied physical theatre, puppetry, mask … I tried to put things together. By the time I was at this performing arts lab, we used it all. So my studies were very useful. It was called theatre anthropology, but we did a lot of choreographic studies and so on. When I got immersed in physical theatre I knew I could incorporate dance. I studied physical theatre, puppetry, mask … I tried to put things together. By the time I was at this performing arts lab, we used it all. So my studies were very useful. It was called theatre anthropology, but we did a lot of choreographic studies and so on.

CA: And then your position ended, just like that – you must have been devastated … NA: Yes, it had been the perfect place. It was fantastic. I was the happiest person on earth! I was doing what I loved, and they were paying me … and I had the chance to develop programs, to do workshops, to develop our own kind of training. We were five members – and yes, we were devastated by the closure. Everyone did different things. Some people stopped dancing altogether. CA: Where are we in time now? NA: This was 1987 to 1989. Then I came to Canada. Before leaving Mexico I was the assistant director of the lab program.CA: When you arrived in Toronto in 1989, who did you take class with? NA: Well T.I.D.E. was at that time struggling with the Canada Council. I took classes with Darcey, who was then teaching at the University of Toronto. I took classes at Toronto Dance Theatre occasionally, sometimes with Denise Fujiwara, with Tama Soble who was teaching yoga, and master classes once in a while. I right away started at York. Of course the Master's program didn't have the practical side – but I asked permission to take classes with the undergraduates, and did so whenever I could. I also took theatre movement and voice classes in the city with a variety of people. CA: I think it's important to have a practice, while doing anthropological work – that's where the fascination comes from, it comes from the bones …NA: Yes, and sometimes we don't even know why we're doing what we're doing until later. From the beginning at the Laboratory of Performing Arts in Mexico, my tendency was to follow a more indigenous approach. The funny thing is I didn't know I had an indigenous background until I was a teenager. At that time, indigenous was not a good thing, and, as with many families in Mexico with an indigenous background, my mom grew up without any of her culture or language. Nothing. When I went back to Sonora, I was the one who started teaching my mom about her own culture. I started learning the language, the dances, the culture. It was also difficult for me as a woman – because the dances are danced only by men. I was the first woman to ask permission to do the Deer Dance. They completely laughed at me. They thought I was nuts – they used to call me “The Canadian”. I stayed there for six months. I said, “At least let me do my own interpretation, inspired by the Deer Dance.” And they said okay. I never got permission to do the dance proper, because I'm a woman. I learned it anyway. CA: And saw it performed?NA: The real dance? Yes, I saw it performed; however, I never did it myself. But I created my own interpretation of the Deer Dance and performed it for a while. It developed in many different ways. I call it Dear Deer because of my love for it, and the struggle and fascination. I used some of the steps but I cannot recreate the ritual ceremony.  Since my mom did not grow up aware of this history, I had to go back; though it was not until I was already in Canada and after meeting a lot of indigenous people here. Alejandro Ronceria was one of the people I met right away in Toronto. I was amazed by the difference from Mexico – it is so multicultural here, with people from all over, doing their thing. At least at the more superficial level, there was no repression – there was a lot more freedom to express. I really got inspired, and that's one of the reasons I wanted to take that opportunity at York to go back to my roots. I was inspired by the people around me. Since my mom did not grow up aware of this history, I had to go back; though it was not until I was already in Canada and after meeting a lot of indigenous people here. Alejandro Ronceria was one of the people I met right away in Toronto. I was amazed by the difference from Mexico – it is so multicultural here, with people from all over, doing their thing. At least at the more superficial level, there was no repression – there was a lot more freedom to express. I really got inspired, and that's one of the reasons I wanted to take that opportunity at York to go back to my roots. I was inspired by the people around me.

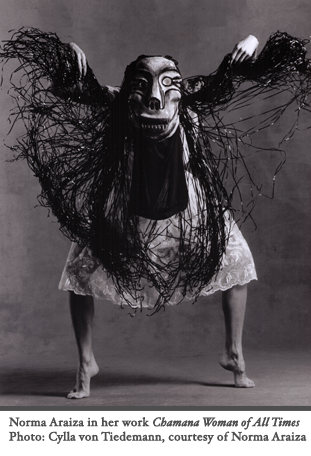

CA: Was Nina De Shane there at that time?NA: Oh yes! Nina was my angel and my thesis advisor. I don't know what I would have done without her. Because of her I had the opportunity to teach right away, as soon as I finished my last year. Cultural studies first, and then the dance department – I did a bit of that – thanks to her. With Zelma Badu [another York MA graduate], I created and taught a cultural studies course. CA: That was a time of shifting perspective about diverse forms in the dance community. NA: It was very interesting to me that the first fFIDA (fringe Festival of Independent Dance Artists) happened in 1990. I'd been here just a year, and I thought, “I have to continue with my work,” though I was still a bit in shock with all the changes in my life. I was rehearsing at Scadding Court – the changing rooms are not used in the summer and are quite spacious. I was rehearsing there, on the cold concrete, surrounded by tiled walls … I was just getting to know how things work. I did my first dance/theatre piece here based on Maria Sabina who was a shaman, a medicine woman from the Mazatec Nation. It was very ritualistic, a twenty-minute solo. Tama Soble saw it and said, “Wow, this is something else.” I presented it at fFIDA and people were saying, “What the hell is this?” It didn't have a lot of dance virtuosity; it was very grounded, percussive, with a big mask. People didn't know what to think about me. Learie McNichols said, “You have to come dance with us at Dancemakers!” But everyone else said, “Interesting …”I didn't really care. I was so happy that I was able to develop a twenty-minute solo. When I see it now I think, “Wow, that was brave!” because no one was doing anything like that at the time. It seemed strange; it was not according to the aesthetics of Toronto dance. I didn't quite fit …CA: That's good! (next page) | |