| ||||||

“In reality, artists are contemporary and everyone else is behind the times.”

- Jeanne Renaud

Jeanne Renaud has been described by dance historian Iro Tembeck as one of three great pioneers of modern dance and choreography in Quebec. The two others named are her friends and colleagues, Françoise Riopelle and Françoise Sullivan. All are viewed by Tembeck as guides, breaking with earlier traditions, opening doors and showing the way to a generation of modernist dancers and choreographers who would follow. The artistic context that gave rise to this remarkable trio is a study in its own right, but first of all a few words about Renaud's background and early life.

Jeanne Renaud has been described by dance historian Iro Tembeck as one of three great pioneers of modern dance and choreography in Quebec. The two others named are her friends and colleagues, Françoise Riopelle and Françoise Sullivan. All are viewed by Tembeck as guides, breaking with earlier traditions, opening doors and showing the way to a generation of modernist dancers and choreographers who would follow. The artistic context that gave rise to this remarkable trio is a study in its own right, but first of all a few words about Renaud's background and early life.

Born in Montreal in 1928, the youngest of three sisters and an older brother, Louis, Jeanne Renaud enjoyed a life of some ease in the early years. Her father was from a wealthy family and inherited a small fortune, which he eventually lost in the stock market crash. He was also, however, a dentist and professor of dentistry at the University of Montreal. Her mother was a musician and the two made a highly sophisticated couple with friends who were active in the city's arts community. The sudden death of her mother and financial difficulties of her father soon upset this stability. As described by Jeanne Renaud's sister, the late poet and memoirist Thérèse Renaud, in Une mémoire déchirée (1979), what followed were hellish years of torment under a sadistic, hypocritical housekeeper, exacerbated by a repressive convent education. Jeanne Renaud's own memories are less melodramatic, more positive, perhaps because she was (as her sister describes her) brilliant, highly practical and naturally diplomatic. Jeanne is more inclined to talk about the magnificent collection of books on art and  literature their father put at the girls' disposal, in spite of the fact that some of the titles were on the church's forbidden list. In any case, both younger sisters assert that for a number of years, an unhappy family atmosphere was relieved by the intelligence, enthusiasm and adventurous spirit of their elder sister, Louise, the true mother of the family, according to Jeanne, even after their father remarried. And though their father may have been at times distracted and distant, he was willing to support as much as he could, often despite misgivings, the artistic aspirations, education and travels of his maturing daughters. And these were adventurous young women. Louise became a student of visual arts at the École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Montreal from 1938-1942, and this led to the eventual encounter of all three sisters with a community of artists that would not only affect their own lives, but help shape the modern cultural landscape of Montreal, and indeed of Canada.

literature their father put at the girls' disposal, in spite of the fact that some of the titles were on the church's forbidden list. In any case, both younger sisters assert that for a number of years, an unhappy family atmosphere was relieved by the intelligence, enthusiasm and adventurous spirit of their elder sister, Louise, the true mother of the family, according to Jeanne, even after their father remarried. And though their father may have been at times distracted and distant, he was willing to support as much as he could, often despite misgivings, the artistic aspirations, education and travels of his maturing daughters. And these were adventurous young women. Louise became a student of visual arts at the École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Montreal from 1938-1942, and this led to the eventual encounter of all three sisters with a community of artists that would not only affect their own lives, but help shape the modern cultural landscape of Montreal, and indeed of Canada.

In the last years of World War II, a group of young people from a variety of artistic disciplines, including Louise Renaud and others from the École des Beaux Arts, began gathering around the painter Paul-Émile Borduas, who was teaching at the École du meuble (School of Applied Art) in Montreal. Stimulated by Borduas, they became increasingly active, meeting quite regularly at different studios, organizing art shows, public forums, readings and performances of music and dance. By 1946, they had become known as the Montreal Surrealists because of their obvious affiliation with the French movement, but also because of the great emphasis they gave in all their works, in all genres, to spontaneous, free-form expression, as opposed to academic training and realist representation. This group came to include some of Canada's greatest visual artists (Paul-Émile Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle are the best known) and most challenging writers (Claude Gauvreau, Thérèse Renaud and Gilles Hénault among them). When the group, now dubbed the Automatists, published its famous manifesto, Refus global, in 1948, Louise Renaud, Thérèse Renaud, Françoise Riopelle and Françoise Sullivan were among the sixteen signatories. Though now considered a crucial document in the history of modern Quebec, the manifesto was seen at the time as anticlerical and inflamatory, and was roundly attacked from pulpit and pressroom, eventually leading to the sacking of Borduas as an art teacher. Jeanne Renaud agreed with its principles and would have signed it but, not only was she younger than many of the signatories, she was also in New York when the manifesto was published. To explain this, we need to step back a little in time.

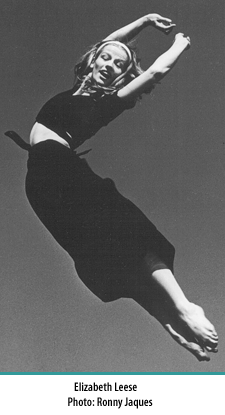

In Montreal, Jeanne Renaud studied music for three years at the famous Vincent d'Indy school of music, as well as classical ballet with Gérald Crevier, a native of Quebec who had studied and danced in England and, when he returned, became well known as a rigorous, demanding teacher credited by the Royal Academy of Dance. Later, she studied modern dance with Elizabeth Leese, a Danish-born dancer who opened a school in Montreal in 1945. Jeanne talks about Elizabeth Leese as a beautiful dancer, and a teacher who gave a good class, but who never talked about music and dance, or the value of the arts in general (and this, as we shall see, was a life-long preoccupation with Jeanne Renaud). Leese taught modern dance and ballet, and was still very involved with the latter, though it was she who mentioned Hanya Holm as probably closer to Jeanne's interests than Martha Graham, for example. In a 1997 interview with Montreal-based presenter Dena Davida, Jeanne talked about those crucial months when, as a teenager, she became fascinated with modern dance:

In Montreal, Jeanne Renaud studied music for three years at the famous Vincent d'Indy school of music, as well as classical ballet with Gérald Crevier, a native of Quebec who had studied and danced in England and, when he returned, became well known as a rigorous, demanding teacher credited by the Royal Academy of Dance. Later, she studied modern dance with Elizabeth Leese, a Danish-born dancer who opened a school in Montreal in 1945. Jeanne talks about Elizabeth Leese as a beautiful dancer, and a teacher who gave a good class, but who never talked about music and dance, or the value of the arts in general (and this, as we shall see, was a life-long preoccupation with Jeanne Renaud). Leese taught modern dance and ballet, and was still very involved with the latter, though it was she who mentioned Hanya Holm as probably closer to Jeanne's interests than Martha Graham, for example. In a 1997 interview with Montreal-based presenter Dena Davida, Jeanne talked about those crucial months when, as a teenager, she became fascinated with modern dance:

[When Anna Sokolow] came to give some master classes in Montreal, I was in them. I had taken classes with Elizabeth Leese, and knew how to do Graham.… Then she looked at me and said, “What kind of dancer would you like to be?” and I said, “I want to be a modern dancer!” I was only fifteen years old. So she said, “Go, quick, to New York. Don't stay here. You'll never make it.” And I eventually went, but I never went to her [Sokolow's studio].

Meanwhile, Jeanne's sister Louise had moved to New York and attended classes at Erwin Piscator's Dramatic Workshop and Studio from 1943-1945. She also worked for a time as a French-speaking governess for the children of gallery owner Pierre Matisse (son of the painter, Henri) and was part of the family's social life. From this base, Louise not only kept her Automatist friends aware of the avant-garde cultural scene in New York, she was also able to help some of them visit and study in the city. This was the case with Françoise Sullivan, who stayed with Louise while she checked out various options before gravitating to the studio of Franziska Boas. Jeanne Renaud followed the same route in 1946, except that she opted for studying and working with Hanya Holm, for whom Alwin Nikolais and Mary Anthony were teaching. But before she went, during the summer of 1946, she collaborated with Françoise Sullivan in a dance performance in Montreal. There are photos of Jeanne Renaud and Françoise Sullivan rehearsing Sullivan's Dualité on the grounds of the Renaud summer home. Louise and Françoise had returned from New York for the summer.

©2009, Dance Collection Danse

Jeanne Renaud Exhibition Curators: Ray Ellenwood and Allana Lindgren

Web Design: Believe It Design Works

Gérald Crevier