| ||||||

Having worked part-time in New York as a teacher with the New Dance Group, substituting for Mary Anthony, Jeanne Renaud went to Paris in December of 1948, where her new husband, Jean-Pierre Labrecque, would continue his medical career by studying psychoanalysis with Jacques Lacan. They travelled with Françoise and Jean-Paul Riopelle and their infant daughter, Yseult (a future dancer), and were met in Paris by Thérèse and Louise and their new partners. Thérèse had left Montreal for Paris in 1947, and had recently married Refus global painter and signatory Fernand Leduc, who had come to Paris after her. At one point all three sisters and their partners were on three floors of the same house, a family reunion that resulted in conversation that Jeanne Renaud still recalls with pleasure, fuelled by their varied cultural interests. After all, Leduc was a philosopher of art as well as a painter, Labrecque had turned to psychoanalysis because of his broad literary/cultural interests, and Francis Kloeppel, Louise's future husband, was working on a book on the French poet Gérard de Nerval. As for the general cultural atmosphere of the city, Jeanne Renaud's own words best describe it:

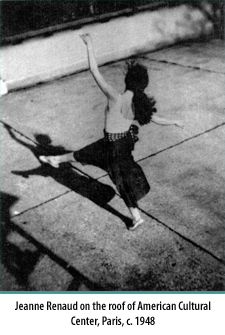

[After the stimulation of New York] in Paris, all seemed distant, even cold. Needless to say, modern dance was totally ignored and I felt out of place in this universe of museums and rationality. At first, I even regretted my decision to follow my partner, and it took me a while to recover. But then I decided to find a studio where I could do my own work. As chance would have it, I discovered a fabulous space at the American Cultural Center on Boulevard Raspail, free in exchange for some classes I gave to Americans and a few French neophytes.

[After the stimulation of New York] in Paris, all seemed distant, even cold. Needless to say, modern dance was totally ignored and I felt out of place in this universe of museums and rationality. At first, I even regretted my decision to follow my partner, and it took me a while to recover. But then I decided to find a studio where I could do my own work. As chance would have it, I discovered a fabulous space at the American Cultural Center on Boulevard Raspail, free in exchange for some classes I gave to Americans and a few French neophytes.

I met a dancer from the Martha Graham company, Helen McGee, who was living through much the same experience I was. She was on holiday in Paris and I met her during a recital-demonstration she was giving on the “Graham technique”. She was a fabulous technician and dancer, but she was so inhibited by the Graham style, her own creative powers were stilted.

So I decided to give my own recital in a theatre gladly lent to me by the American Club. I asked my friend Pierre Mercure, who had come to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, to write music for the show, as he had already done earlier in Montreal. He was happy to offer his services, along with wife and friends: Monique Mercure played the cello, Gabriel Charpentier the piano, Mercure the bassoon, and Jérome Rosen the clarinet. Rosen composed a work for one of the dances on the program. Jean-Paul Riopelle agreed to do the stage set. He asked me how much I could spend … as little as possible, as usual!

In fact, everything was pretty much spur-of-the-moment. I'd go to the Mercure's for rehearsals and was astonished to find the music different every time. Right up to the last minute, I didn't have much idea what I'd hear at the show. Mercure glanced at the choreography once or twice, no more. As for Jean-Paul, when I'd ask him how preparations for the set were going, his reply was always, “Don't worry, I'll tell you when the time is ripe.” My patience was wearing thin. Françoise Riopelle, a very good seamstress, suggested she could help with the costumes. I finally printed a program and sent out invitations to people who were on the list of invitees of the American Cultural Center. Riopelle's name wasn't on the program (it didn't much matter, since we were all complete unknowns to the American Club audience) because I didn't know what he was going to do, if anything. It was only later that I understood his hesitation, given the scarce technical resources, not to mention problems with lighting! All he had at his disposal was a rudimentary set of footlights at the front of the stage. He found a solution two days before the show: with a slide projector we'd rented, he created a setting out of projected slides which he modified by painting on them. But he found the effect too static, so he pulled some hairs out of his head and threw them in front of the slides. They melted and twisted in contact with the heat of the lamp, giving an astonishing, dynamic effect. I was completely amazed. I wondered if my dance was still needed, but Riopelle reminded me the set was there because of my performance. As background for one of the dances, he'd chosen a painting by Giorgio de Chirico showing a wide open space. It worked perfectly because, in fact, my dance needed a perspective much larger than the theatre stage could offer. Riopelle found solutions for everything. His imagination was extraordinary. My worries vanished at the last minute, and Helen McGee, who was there for the show, was astonished and enchanted. She wrote me later to say how sorry she was for having turned down my invitation to take part.

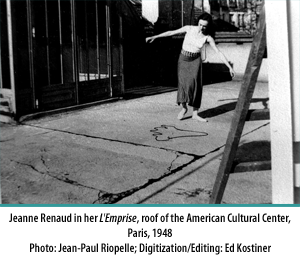

This type of spontaneous collaboration with artists in various media is in the spirit of the Automatist group and very typical of Jeanne Renaud's work throughout her career. The date of that concert was March 1950. Among the works were L'emprise (Control), which had been created in New York but was not performed in the 1948 recital in Montreal. This was the dance, with music by Pierre Mercure, for which Riopelle provided the illusion of space by showing a slide of a de Chirico painting. It has three sections; in the first, the dancer approaches a length of cord on the floor and picks it up; in the second section the rope, an object of fascination and fear, becomes menacing, entangling, even strangling, and is cast off; in the third, the dancer picks up the rope and exits, not triumphantly or nervously but contemplatively.

This type of spontaneous collaboration with artists in various media is in the spirit of the Automatist group and very typical of Jeanne Renaud's work throughout her career. The date of that concert was March 1950. Among the works were L'emprise (Control), which had been created in New York but was not performed in the 1948 recital in Montreal. This was the dance, with music by Pierre Mercure, for which Riopelle provided the illusion of space by showing a slide of a de Chirico painting. It has three sections; in the first, the dancer approaches a length of cord on the floor and picks it up; in the second section the rope, an object of fascination and fear, becomes menacing, entangling, even strangling, and is cast off; in the third, the dancer picks up the rope and exits, not triumphantly or nervously but contemplatively.

Other dances not seen in Montreal included Danse marine (with costumes by Françoise Riopelle and again with projections by Jean-Paul Riopelle of a painted slide “animated” by movements of the artist's burning hair thrown in front of the hot lamp), and Rythme, accompanied by percussion instruments. The dance called Déformité in Montreal was given the title Nuit infernale in the Paris recital, probably after the poem by Max Jacob (who died in a concentration camp shortly before the end of the war) that was recited during the performance.

In her brief memoir about the Paris years, Jeanne Renaud also talks about seeing Merce Cunningham again and taking classes with him when the famous avant-garde musician, John Cage, was acting as Cunningham's accompanist. “The relationship between Cage's music,” she writes, “and the technique taught by Cunningham was most unusual: each provided his own emphasis. For me it was like the freedom I'd enjoyed with the Automatist group. I'd already taken a few classes with Cunningham in New York, but it was in Paris I discovered this marvellous and unique connection between his dance and the music of Cage. I think the contact brought out the energy of each, and that was communicated to the dancers.” She writes of having seen a recital presented by Cunningham and Cage in the studio of the painter Jean Hélion on Avenue de l'Observatoire on June 10, 1949. “But very few people in Paris were open to these experiments in contemporary dance,” she writes. Just as her sister Thérèse found the theatre world in Paris uninviting, Jeanne never found a company of dancers with whom she could work. In a 1997 conversation with Dena Davida, she remarked:

I wanted to teach, wanted to start shaking up the French, but look at the people who came to my class. They were always American with one or two little French ones, and they were the ones who questioned everything, who didn't want to do those movements, couldn't do it, rejected it (laughter). I wanted the French to understand modern dance. There was nothing; they had never seen Martha Graham or anyone else when I arrived there in 1948.

No surprise, then, that Jeanne Renaud took the opportunity to spend about ten days in London making contact again with Mary Anthony (whom she later convinced to go and live in Paris). But if there was not much French interest in modern dance at the time, Paris was still very rich in the other arts and provided Jeanne Renaud with a general knowledge that would serve her well in later years. In late 1952 she left France, pregnant, to return to Montreal.

Her daughter, Michelle, was born in 1952, and her son, Sylvain, four and a half years later. For a number of years, her time was devoted mainly to the raising of her two children, though she was able to do some work in a studio space offered by the children's school. Accepting her husband's wishes that dance should take second place to domestic life, she did her dance work whenever she could find time. For example, in order to retrain her body, she went back to taking ballet classes at the Ludmilla Chiriaeff Ballet School at night. Most important, she was back in contact with Françoise Riopelle, who had returned from Paris in 1953, separated from her first husband and now living with the musician, Pierre Mercure. Here was renewed stimulation for Jeanne Renaud, not only in conversation about music and the arts with her old friends, but also in Françoise Riopelle's need to choreograph modern dances and to find performers. Françoise Riopelle had studied choreography in Europe. Jeanne had not kept up with her work, but now she found herself strongly urged to return to dance in partnership with her friend. Somehow balancing the needs of a total of five children from baby to pre-teen, these women began in a small way, holding what might be called chamber recitals of dance, for about twenty people, in the large house owned by the Mercures. At first they did the performances themselves, sometimes inviting Birouté Nagys and later using dancers borrowed from the Chiriaeff School, but more and more they felt the need to train their own dancers as Jeanne began to choreograph again.

©2009, Dance Collection Danse

Jeanne Renaud Exhibition Curators: Ray Ellenwood and Allana Lindgren

Web Design: Believe It Design Works

Récital de Danse

program, 1950