| ||||||

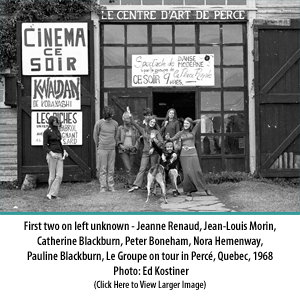

In 1966, at the strong urging of one of her dancers, Peter Boneham, Renaud founded Quebec's first official company of modern dancers, Le Groupe de la Place Royale. Le Groupe was not the first modern dance company in Canada. Earlier groups included Rachel Browne's Winnipeg's Contemporary Dancers, which was established in 1964, and the Paula Ross Dancers, founded in 1965. However, Le Groupe does hold the distinction of being the first modern dance company to receive funding from the Canada Council, which it was awarded in 1966.

In 1966, at the strong urging of one of her dancers, Peter Boneham, Renaud founded Quebec's first official company of modern dancers, Le Groupe de la Place Royale. Le Groupe was not the first modern dance company in Canada. Earlier groups included Rachel Browne's Winnipeg's Contemporary Dancers, which was established in 1964, and the Paula Ross Dancers, founded in 1965. However, Le Groupe does hold the distinction of being the first modern dance company to receive funding from the Canada Council, which it was awarded in 1966.

Other sources of income included Renaud's husband, who generously assisted in providing funding for the new company. In addition, to help pay for the rent and to financially support the company, Renaud opened a school. She taught the modern dance classes, and avant-garde choreography methods while Peter Boneham taught the ballet technique classes.

Although billed as a dance company, Le Groupe de la Place Royale carried on the interdisciplinary spirit of Renaud's other choreographic ventures and quickly became a centre for interdisciplinary experimentation because Renaud was very interested in the potential creativity that could happen at the intersections of artistic expertise. From the company's inception, press releases and performance notices all encouraged the press and potential audience members to focus on the inclusiveness and collaborative elements underpinning Le Groupe's productions by suggesting that contemporary creative expression was necessarily interdisciplinary: “Le Groupe de la Place Royale wants to work closely with painters, sculptors, composers, poets and other artists to present productions that will appeal to those who are interested in all forms of artistic expression of our time.”

Renaud's desire to dispense with boundaries between the arts was, in part, a result of her exposure to and her autodidactic explorations in a wide variety of artistic milieux early in life. In fact, Renaud deliberately omitted the word “dance” from Le Groupe de la Place Royale's name as a way to signal her broad creative orientation that would have been fettered if placed strictly within the confines and connotations of one artistic discipline. Instead, she chose the name of the square in Old Montreal that was the home to the company's first studio near the corner of Place Royale and rue des Commissionaires at 351 Place Royale. A city square - a gathering place - was an apt fit for Renaud's aspirations.

In the mid-1960s, Old Montreal was not the trendy and gentrified neighbourhood that it is today. It had a derelict atmosphere. Right across the street were high grain elevators, which have since been torn down. Nearby was a building then used for the Customs House. A cheap rooming house was next door. The studio space Renaud leased was small and needed to be renovated. The studio had three columns, which Renaud stripped down and refinished. Likewise, the wooden floors needed to be sanded. One wall had exposed brick, which Renaud left because it seemed stylish.

Some of her dancers, such as sisters Pauline and Catherine Blackburn, were recruited from her school, but Renaud was also lucky that Montreal had a pool of well-trained dancers available to work with her. These dancers, mostly members of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, performed as guest artists with Le Groupe whenever their schedules allowed. It also speaks well of Renaud as an artistic director and as a choreographer that these professional dancers were willing to perform with a small and fledging avant- garde company.

Some of her dancers, such as sisters Pauline and Catherine Blackburn, were recruited from her school, but Renaud was also lucky that Montreal had a pool of well-trained dancers available to work with her. These dancers, mostly members of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, performed as guest artists with Le Groupe whenever their schedules allowed. It also speaks well of Renaud as an artistic director and as a choreographer that these professional dancers were willing to perform with a small and fledging avant- garde company.

One of the most prominent Les Grands dancers to work with Renaud was Vincent Warren. Originally from Jacksonville, Florida, Vincent Warren had a successful career as a principal dancer with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. His chiselled beauty and charm captivated audiences. Moreover, his curiosity about all types of kinetic artistry, which had led him to the postmodern experimentation happening at the Judson Church in New York, was matched by his corporeal facility: he could perform Renaud's modern minimalism with the same ease and precision he demonstrated when starring in the classics of the ballet repertoire with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. During the year, Warren would work with Les Grands in the daytime and then go to Le Groupe to rehearse with Renaud in the evenings. As his status in the ballet company grew, his availability to perform with Le Groupe became more restricted, but Warren always remained dedicated to Renaud's aesthetic vision and protective of her as a friend.

American dancer Peter Boneham had studied with Olive McCue in Rochester, New York, and had performed with several dance companies before coming to Canada, including the Mercury Ballet, the William Dollar Concert Ballet, the Baltimore Civic Ballet, Radio City Music Hall, and as a soloist with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. He relocated to Montreal in 1965 after he was hired by Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. Recommended to Renaud by Warren, Boneham soon resigned from his position at the ballet to work as Renaud's co-artistic director and assistant. His articulate and dexterous intelligence, his organizational skills, seemingly endless energy and steadfast belief in Le Groupe made him an indispensable ally for Renaud.

Other early company members included Nora Hemenway and the Blackburn sisters. Maria Formolo, a dancer noted for her technical precision and disciplined attention to details, joined Le Groupe after seeing the company perform at Expo '67. Rosemary Toombs, a British dancer trained at the Royal Ballet School, joined Le Groupe in April 1968. Before emigrating to Canada, Toombs had danced with London's Festival Ballet, the Hamburg Opera Ballet, and the National Ballet of Holland where Rudi van Danzig set the role of Lady Capulet on her for his successful production of Romeo and Juliet. Company member Jean-Pierre Perreault, who later became one of Quebec's most commended contemporary choreographers, was “discovered” by Peter Boneham in a nightclub. A teenager who had had polio as a child, and a beginner with no previous dance training, Perreault nevertheless had a naturally developed physique for dance. His artistic sensitivity and inherent understanding of movement led Renaud and the other company members to realize quickly that Perreault was destined to become a choreographer.

The final and unofficial member of the company was not a dancer. Ed Kostiner was at that time a talent manager and an independent television producer. By happenstance, one morning in the late 1960s, he picked up Formolo who was hitch-hiking to company class. As they talked about their respective vocations, Formolo became quite animated and invited him to the studio. Kostiner knew very little about modern dance, but decided to visit Le Groupe anyway. He was immediately impressed by Renaud's fearless dedication to artistic experimentation. After he attended a few of the company's performances, he offered to assist. An experienced photographer who, in addition to his other businesses, had developed world-class dark room equipment, Kostiner later designed lighting for some of Le Groupe's productions.

The final and unofficial member of the company was not a dancer. Ed Kostiner was at that time a talent manager and an independent television producer. By happenstance, one morning in the late 1960s, he picked up Formolo who was hitch-hiking to company class. As they talked about their respective vocations, Formolo became quite animated and invited him to the studio. Kostiner knew very little about modern dance, but decided to visit Le Groupe anyway. He was immediately impressed by Renaud's fearless dedication to artistic experimentation. After he attended a few of the company's performances, he offered to assist. An experienced photographer who, in addition to his other businesses, had developed world-class dark room equipment, Kostiner later designed lighting for some of Le Groupe's productions.

Throughout her tenure at Le Groupe de la Place Royale, Renaud invited a wide array of artists to collaborate with her company, including the musicians Serge Garant, Gilles Tremblay and Bruce Mather. Drawing from her connections in visual arts, Renaud also gathered an impressive coterie of talent to create the scenery and costumes for her choreography: Lise Gervais, Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, Susanne Swibold, as well as her Automatist friends Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Marcel Barbeau, Françoise Sullivan and Marcelle Ferron.

Vers l'azur des lyres, one of Renaud's most successful choreographic works, was typical of the interdisciplinary collaboration integral to Renaud's choreography. Inspired by a poem of Paul Valéry, Vers l'azur des lyres was set to vocal and instrumental music for piano and percussion by Bruce Mather. The decor was created by Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, a talented weaver who made a huge woven flat for the backdrop and three woven blue pillars that looked more like sculptures than tapestries in the dark blue light that flooded the stage as the curtain rose.

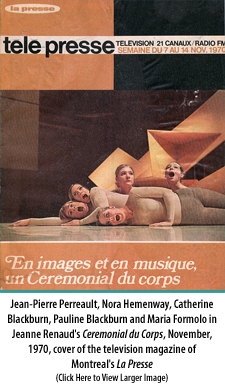

Another work, Cérémonial du corps (1969), which was performed on television in 1970 by dancers Maria Formolo, Catherine Blackburn, Pauline Blackburn, Nora Hemenway, Jean-Pierre Perreault and Peter Boneham, played with the Merce Cunningham-John Cage method of creative collaborations in which the various contributing artists were unaware of what each other was doing. According to Serge Garant, who composed the score:

Each [artist] was to work separately according to a basic scheme provided by Gabriel Charpentier (artistic consultant at Radio-Canada): a form with very precise variations lasting twelve minutes, with a core lasting fifteen seconds, developing in two directions at fifteen-second intervals. Into this music would be integrated, at irregular intervals, a series of poems. Armed with this information, all of the collaborators - set designers, costume designer, choreographer and composer - each having worked in isolation, were able to provide the producer [Pierre Morin] the elements from which grew the visual and auditory poem, Cérémonial du corps.

The artistic energy in Montreal in the mid- to late-1960s was particularly active and creatively charged. There were other modern dance choreographers in Montreal at the time, including Françoise Graham, Alex MacDougall and Birouté Nagys, but Renaud was a particularly important catalyst who had an unrivalled talent for bringing out the best in artists. She also encouraged her own dancers to immerse themselves in culture as she had done while a student in New York. “How can you be an artist if you are not aware and surrounded by creation - to make you more generous and open …” she told them on more than one occasion. In turn, the city's artists flocked to Le Groupe's performances, which generated creative energy and a sense of adventure. The dancers were young. They had beautiful and articulate bodies. They were performing choreography on the edge: unsentimental, intellectual, hip. For those who could envision Montreal as a world-class city, Le Groupe signified the future.

The artistic energy in Montreal in the mid- to late-1960s was particularly active and creatively charged. There were other modern dance choreographers in Montreal at the time, including Françoise Graham, Alex MacDougall and Birouté Nagys, but Renaud was a particularly important catalyst who had an unrivalled talent for bringing out the best in artists. She also encouraged her own dancers to immerse themselves in culture as she had done while a student in New York. “How can you be an artist if you are not aware and surrounded by creation - to make you more generous and open …” she told them on more than one occasion. In turn, the city's artists flocked to Le Groupe's performances, which generated creative energy and a sense of adventure. The dancers were young. They had beautiful and articulate bodies. They were performing choreography on the edge: unsentimental, intellectual, hip. For those who could envision Montreal as a world-class city, Le Groupe signified the future.

During its first season in 1966/67, Le Groupe performed at an impressive number of venues. Beginning in October, Renaud and her dancers appeared at the library in St. Sulpice, the Théâtre de l'Égrégore, the Théâtre Maisonneuve, the Pavillon de la Jeunesse at Expo '67, and the Bibliothèque Nationale. The following season, Le Groupe expanded its exposure exponentially by appearing on Radio-Canada television's Les Beaux Dimanche. The early programs were usually dominated by the choreographic works of both Renaud and Boneham. A January 1969 concert was typical: the dancers opened the evening with Boneham's Chigoamigon, which was followed by Renaud's Sur un poem de St. Denys Garneau. Next on the program was They Follow One Another Inside of Tomorrows by Renaud. The final piece of the evening was La TERRE est BLEUE comme une ORANGE by Boneham.

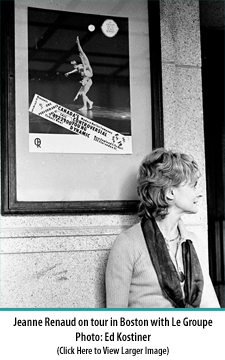

Early touring engagements took the company to Quebec City where the dancers performed at the Palais Montcalm Theatre, with a later stop at the Centre Culturel de Shawinigan. By the time she left the company, Renaud had overseen tours to Bishop's University in Lennoxville and as far south as Boston; Providence, Rhode Island; and Baltimore.

Renaud's intellectual aesthetic in the 1960s was, ostensibly, most influenced by the New York modern dance choreographer Merce Cunningham. “Merce was probably the one that made me aware of what was considered [by] me to be the evolution of modern dance. He was the epitomy of modern dance,” she told one interviewer. For her Montreal dancers, Renaud adapted the post-World War II trend toward formalism that was so closely associated with Cunningham, pursuing her curiosity about the body in motion devoid of emotional impetus. The formal elements of dance, particularly body and spatial shapes, dominated her aesthetic at the time.

Renaud's intellectual aesthetic in the 1960s was, ostensibly, most influenced by the New York modern dance choreographer Merce Cunningham. “Merce was probably the one that made me aware of what was considered [by] me to be the evolution of modern dance. He was the epitomy of modern dance,” she told one interviewer. For her Montreal dancers, Renaud adapted the post-World War II trend toward formalism that was so closely associated with Cunningham, pursuing her curiosity about the body in motion devoid of emotional impetus. The formal elements of dance, particularly body and spatial shapes, dominated her aesthetic at the time.

Seeking to clarify her style, she told the press “People usually call our works abstract. Yet for me there cannot really be abstract dance because you can't have an abstract human body. However, if by abstract you mean that we are more concerned with problems of space, form and volume than with telling a story, then I suppose you could say our dances are abstract.” Certainly, any vestiges of story or representation were rejected; sound accompaniment might be provided by objects attached to the dancer's costumes such as white discs hanging from the dancers' arms in Renaud's work Blanc sur blanc (1964), or by the set itself, as in Rideau sonore, danced in 1965 by Jeanne Renaud and Peter Boneham through and around a decor of wire and hanging metal (from which came the sound effects) created by Françoise Sullivan. Movements in these dances were often slow, controlled, linear.

Some critics found this kind of work too intellectual, others found it too audacious, as with the filmed nude version of Renaud's Karanas, performed by Maria Formolo and Jean-Pierre Perreault in 1968 - a remarkable study in understated, cool sensuality. Karanas featured two dancers performing on stage, clothed, in front of a film of company members Jean-Pierre Perreault and Maria Formolo dancing a pas de deux, both completely nude. While it is unclear if Renaud was influenced by or even aware of the musical Hair, which premiered off-Broadway in 1967 and then opened on Broadway in 1968, her use of the dancers' naked bodies reads less as a comment on the sexual freedom of the hippy lifestyle than a paring down of the performers to their individual corporeity. The day of the dress rehearsal before the work's premiere, Renaud was asked by the theatre's administration if she had received permission from the censor board to show the film. Flustered and unaware that she needed government approval, Renaud took her film to the appropriate authorities and waited for their response. The answer, which came in time for the performance to proceed, was more positive than the reviews issued by some of the critics. It praised Renaud for her artistic sensitivity.

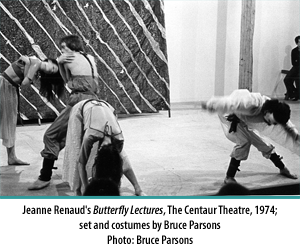

Between 1962 and 1970, Renaud choreographed and performed in thirty-two works. Even in 1974, after she had officially left the company, she continued her association with Le Groupe de la Place Royale, choreographing a dance for them, Butterfly Lectures, in collaboration with the visual artist Bruce Parsons. In her comments related to this work she describes herself as a kind of catalyst, “hoping to trigger the creative capacities of different kinds of artists, dancers and others,” rather than a choreographer who simply sets movement.

Between 1962 and 1970, Renaud choreographed and performed in thirty-two works. Even in 1974, after she had officially left the company, she continued her association with Le Groupe de la Place Royale, choreographing a dance for them, Butterfly Lectures, in collaboration with the visual artist Bruce Parsons. In her comments related to this work she describes herself as a kind of catalyst, “hoping to trigger the creative capacities of different kinds of artists, dancers and others,” rather than a choreographer who simply sets movement.

In the spring of 1969, Renaud and Le Groupe's fortunes took a turn for the worse. In retrospect, a negative review marked the beginning of the end of Renaud's leadership with the company she had founded. The company had been performing at Place des arts. A local newspaper critic for the Montreal Star, Zelda Heller, was in attendance and wrote a scathing review of Le Groupe. She implied that all the audience was as displeased as she had been. Angered, Boneham called Heller and chastised her for suggesting that she spoke for the rest of the audience. Shortly afterwards, Renaud received an invitation to meet with an editor from the paper. In the end, Renaud brought Peter Boneham with her. A reviewer who had worked for the Village Voice and had seen the production also attended.

The atmosphere at the gathering, which was held in the apartment of a music critic, became friendly over the course of the evening. Thinking the discussion was off-the-record, Renaud candidly expressed her opinion on a range of topics, including the Canada Council. Unfortunately, shortly afterwards an article appeared in the paper with the headline, “Who's killing modern dance in Montreal? The critics? The choreographers? Or would you believe the Canada Council?” To Renaud's horror, her comments about the federal funding agency had been published. According to Peter Boneham, within three days of the article, Le Groupe lost its funding. Employees of the Canada Council at the time later denied Boneham's charge, citing that the assessment process in place prevents the Council from interfering with grants, but members of Le Groupe remain steadfast in their belief that the company was financially punished for its artistic director's public statements.

The atmosphere at the gathering, which was held in the apartment of a music critic, became friendly over the course of the evening. Thinking the discussion was off-the-record, Renaud candidly expressed her opinion on a range of topics, including the Canada Council. Unfortunately, shortly afterwards an article appeared in the paper with the headline, “Who's killing modern dance in Montreal? The critics? The choreographers? Or would you believe the Canada Council?” To Renaud's horror, her comments about the federal funding agency had been published. According to Peter Boneham, within three days of the article, Le Groupe lost its funding. Employees of the Canada Council at the time later denied Boneham's charge, citing that the assessment process in place prevents the Council from interfering with grants, but members of Le Groupe remain steadfast in their belief that the company was financially punished for its artistic director's public statements.

Whatever the truth, records show that the company requested a meeting with the funding agency in July 1969, to discuss the matter. It was suggested that Le Groupe had over-extended itself. Though comments from the Council were seen by Le Groupe as paternalistic, there was nothing to be done, and the company struggled on with limited financing for the next two years. In April 1971, Jeanne Renaud learned that Le Groupe would not receive its annual Canada Council grant, and by mid-July 1971, the company was in the midst of another serious crisis. The Chairman of Le Groupe's Board of Directors and the other officers resigned without holding a formal meeting. Lacking a Board, Le Groupe could not function as a legal entity. Renaud decided to continue anyway. She managed to secure a $5,000.00 grant from the Canada Council, but without the signing authority of a Board, the cheque could not be cashed. That summer, Renaud resigned and left the company under the directorship of Peter Boneham.

Financial and administrative frustrations were not the only reason that Renaud decided to leave Le Groupe. She had begun to feel like she had said all she could choreographically within the company's structure:

I was questioning everything. I was afraid that if I didn't, I would develop a system. I had developed a way of working with form, shape, space, rhythm and energy and I knew how, in my abstract forms, to cut things up and put them together again … I had explored as much as I could, and didn't have the challenge that I was looking for in my creative work. So I broke away completely and started again.

I was questioning everything. I was afraid that if I didn't, I would develop a system. I had developed a way of working with form, shape, space, rhythm and energy and I knew how, in my abstract forms, to cut things up and put them together again … I had explored as much as I could, and didn't have the challenge that I was looking for in my creative work. So I broke away completely and started again.

She wanted to start over again as a choreographer. She wanted to experiment with new movement ideas. She wanted the freedom to play as an artist. Yet, Renaud's urge to reinvent herself artistically at Le Groupe would have meant asking the dancers to abandon their technique and to begin anew as well. It also meant rejecting the established aesthetic of the company, and risking the possibility of alienating audiences and critics.

The early 1970s also marked the end of her marriage. At the time, leaving all that was familiar appeared to be the most logical choice for her professional and personal problems.

In the final analysis, though the response of critics and arts administrators was often uncomprehending, Le Groupe de la Place Royale was very successful in taking Canadian modern dance to a wide public, with performances at the Place des Arts in Montreal, tours in the United States, and exposure through the new world of arts programs on television.

©2009, Dance Collection Danse

Jeanne Renaud Exhibition Curators: Ray Ellenwood and Allana Lindgren

Web Design: Believe It Design Works

Rideau sonore, 1965