|

next page l previous page Big projects seemed to fall into my hands – I did more work in theatre and television – even acting in a couple of specials with Mr. Dressup. That was sweet!

I worked with a lot of people, in Toronto, in Montreal, in Vancouver – I started to be in demand more, and at the same time I started working on my own. Later, I got a commission to go to Germany, along with touring in Spain and France. When I came back, I found out that René was sick. That was very hard – we hung out together all the time. And then he passed away …CA: Moving forward from that time, can you speak about your work and describe how you got interested in film?AR: I moved into working in the theatre, and then film work. I had an agent and was doing auditions. It was a natural progression, and I had a number of roles. The seductive thing about film is that it pays well – what I made in one day was about what I'd make in four months as a dancer! Things started to roll very fast, and I got recurrent roles in TV series. Not the greatest acting roles, but at the same time I learned through the process of waiting around that goes with filming. Instead of wasting my time waiting, I went behind the camera and learned camerawork – camera positions, movement and so on. I worked on a film directed by Norman Jewison. Seeing him direct was great – I went behind the camera, a very quiet shadow. I loved his passion. He was a master – he conducted the whole thing – animating the actors from behind the camera. He was the conductor. I learned a few things about film and was thinking, “No one is going to write the roles I need to express myself.” So I moved into writing, producing and directing. I directed a couple of shows and won a couple of awards. Then I got a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts to go into the jungles in South America, to five different countries, to the highlands and the coasts. They said, “This is a huge project,” but somehow they gave me the grant. I wanted to research traditional dance in Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia and some parts of the jungle in Brazil. I wanted to compare, find similarities and parallels among them and with traditional dances of North America, Canada. So I went ahead and did that.I was inspired by Alvin Ailey and by butoh … how dance comes from the roots. I was inspired by how Ailey built everything, his company and school, and traced African-American experience, and translated those African dance roots onstage in works such as Revelations – his wonderful, classic masterpieces. Then with butoh, how the tragedy and devastation of war came through this form. It's unique, with an authentic voice. After gathering all these thoughts, from European theatre, ballet, opera, cinematics and working with René and Tomson Highway, I wanted to investigate what we have here, on this continent. It was very ambitious, and still is. I've barely scratched the surface … I wanted to go backwards, to explore the musicality and the movement and ritual and where that originated. I wanted to investigate how powwow dancers could go for two days without stopping … In ceremonies you dance four or five hours and never get tired, and re-energize yourself. But there are very clear structures; there are protocols. I wanted to see how we hear this musicality, how the body interprets that. What is the vocabulary of how it is manifested? That's been my field since then, after going back to Colombia and seeing traditions, and where they came from, and retaining all that knowledge. Then with all my background, my acquired knowledge of the stage and theatre, of lighting, outlining, scripting, thinking about how to do something with dance on the continent. CA: Can you speak about your work with the Aboriginal Dance Program at The Banff Centre? Red Belt from the performance of Chinook Winds, The Banff Centre, 1996

Choreography: Alejandro Ronceria

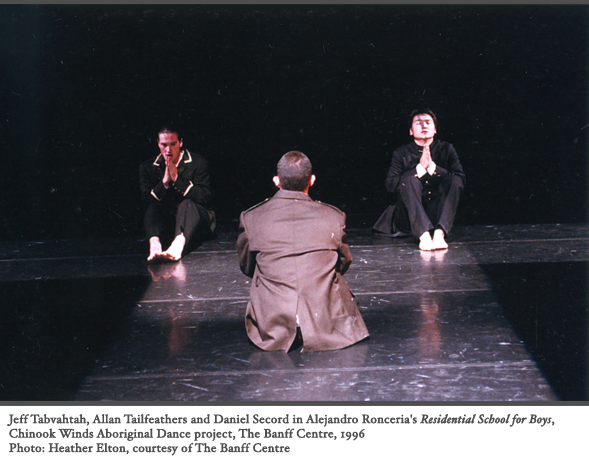

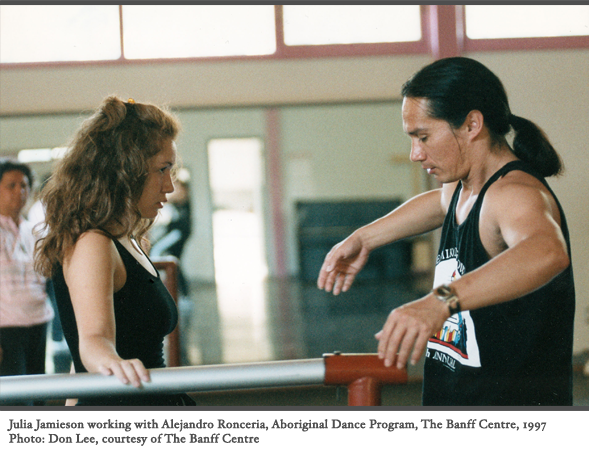

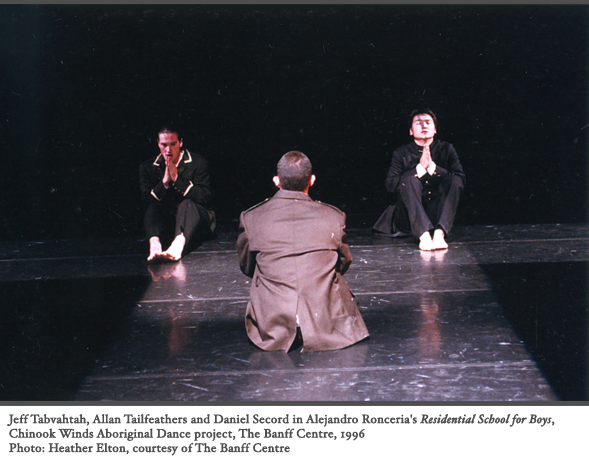

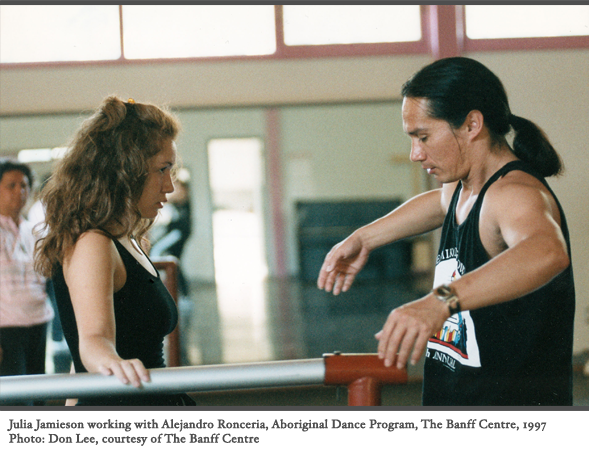

Music: Russell Wallace AR: Though René left us, left the physical world, he's still with us and still manifests in the physical work today. Raoul Trujillo has been very successful, first in theatre then in film, and continues to be very successful. He just did a piece with Santee [Santee Smith's TransMigration, Harbourfront Centre, May 2012]. It was a movement; as the aboriginal theatre movement was beginning, René was a pioneer in North America – and then disappeared. Marrie Mumford had circles at the Native Centre in Toronto – one of the things she said was, “We need training.” I did a few pieces, but felt people didn't understand the issues I was working with, and that was very difficult. I felt these were vacuum years. It was no one's fault – it takes time and experience … Pina Bausch's dancers, for instance, were with her for long periods, and everyone was very attuned to that German experience, and her art, through her eyes and through the eyes of the performers too. So to me it was very important to train people. I thought, “I need dancers to make the work I want to create, and I want to form them because it's the only way.” I was influenced by Béjart's idea for his school Mudra, where training dancers did fight scenes, the conga, all kinds of crazy things to enrich the process of becoming performers. Following this need for training, we went to The Banff Centre for the Arts and proposed our ideas, and they were accepted. That was the beginning of the Aboriginal Dance Program, in 1996. So then – I had to do this! My idea was to bring the masters, and the masters are the traditional dancers. Through their experience and teaching, we started to see all the methodology, the protocols and thousands of years of knowledge. Then the question was how do we re-interpret and work with that? We moved forward by trial and error and persistence, too, as we explored what is traditional and what is non-traditional, what is “right”, what is not right. You have to learn what things you cannot touch in these cultures, what belongs only to a culture and its ceremonial dance. And what is the social dance, and how can you work with that knowledge? How can you bring it to the theatre, stage it and tell a story, following those lines – the rich culture, the dance of this continent's Aboriginal people that reaches back thousands and thousands and thousands of years?

I found out all this, and I was awed by the program's unfolding – “This is humungous,” I thought, “This is giant!” Nevertheless, I submerged myself in it. Before that, I did the Jaguar Project – it was a solo that I did at the Native Centre. The director of the Du Maurier World Festival came to see it and invited me to perform at the World Festival. Then I went on tour. It was basically an exploration inspired by all my experiences of indigenous dance and culture, especially from my background in Colombia. Continuing, it was work, work, work. I did research funded by Canada Council. I went to the jungles and did rituals in different communities. One in particular, the Ayahuasca, was very meaningful, a life-changing experience with a shaman in the jungle. I came back and did a piece called Ayahuasca Dreams (1994). This was about events in South America while I was there – there was the Shining Path in Peru, there was war and devastation, there was hunger, there was injustice against Aboriginal people. I was basically one on one with all of this. I was all alone with the camera, travelling all over the place, a witness. Sometimes I think I had a guardian with me, because I was in the middle of the jungle and in really hard circumstances – bombs and violent situations. That was a very humbling experience.I also made a film called The Three Sevens co-directed with Jorge Lozano. At times I felt frustrated; there were a lot of bad scripts, and there was a lot of drug culture on the street. I wanted to do something that would identify me. The film was twenty-one vignettes of one-minute encounters – some encounters happened around Oka, and some were between Aboriginal people and me in different situations in Toronto. The film was successful, and we opened for the Toronto International Film Festival, and also went to Sundance – and then everywhere. Unexpectedly – you don't do these things with success in mind, but for the necessity of expression. To me, what we do in dance is so ephemeral and has such a short life. Coming from Colombia, where theatre runs two or three months, or a year if you're successful, with good houses every night, is a huge contrast to here, where dance may run for one week. It's a lot of work to do for a short run. (next page) | |