|

next page l previous page

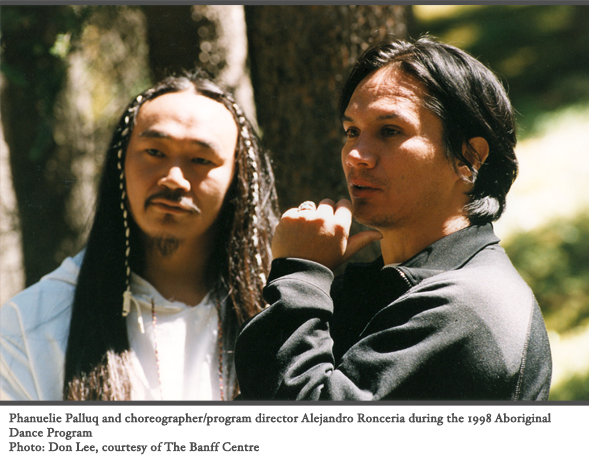

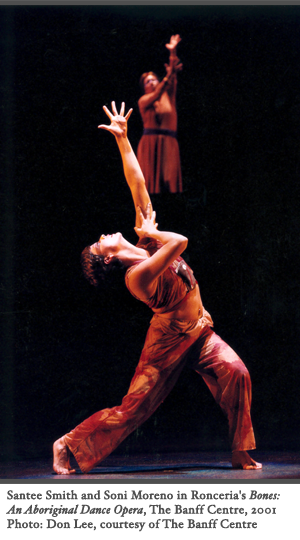

I thought – “How can I do this?” – and decided on film so I'd have longevity. After Ayahuasca Dreams, I wanted to base a work on the hunter, from all that research I'd done. The piece became very successful both here and in the U.S. A Hunter Called Memory, made in 1996, was my first solo dance film. It still had an omnipotent voice – in Spanish and English. It was a success on the international film festival circuit. Sundance took it, New York, Palermo, France – it was fantastic. It went all over the place. But my love still struggled between dance and film. Everyone here was saying, are you a choreographer? A dancer? An actor? A filmmaker? A visual artist? I don't want any label. I was having a hard time, because even peers didn't know how to approach the work as advisors on juries. I was bounced from place to place, from dance to film … I got lucky and Toronto Arts Council, Ontario Arts Council and Canada Council have been very strong supporters of my work – once they saw what was going on; but it was hard to break in.People started to understand the work. I live in Toronto, but don't show that much work here; a lot of the work has been commissioned somewhere else. But I've also done a lot of work here. I did Ancient Rivers (1993); I brought Michael Greyeyes in, and that was a great experience. I did The Maid of the Mists at Buffalo State College with a symphony orchestra and Repertory Dance Theatre from Utah. I also did a lot of choreography for theatre during that period, project after project with Tomson Highway, but also with Native Earth – I ended up being one of the co-directors of the company for three years. This was more of a training role. When I think of co-founding Banff with Marrie [Mumford], I did the whole program foundation, designing and planning the training, by trial and error, every year learning, and every year implementing improvements, building – like anywhere else when you start a new program. CA: Can you speak about what has changed – what effects do you see from your work?  AR: I worked at Banff seven years. The legacy is there – there's still a funded program. They run a summer program. It's a different shape and form; it's been re-invented, as it should be. My motivation at the time I was there was that I needed dancers, and this was the time and place to do it; so they came in to a six-week learning process, and we had a presentation. It paid off. The participants learned new skills and traditions. It was very, very demanding. At the same time, I was training choreographers – my whole idea was that we need to train choreographers and designers; we need composers, everyone, to grow capacity. Also my agenda contained the need to reach out internationally. So we did – to Mexico, Colombia, New Zealand, Australia, the U.S. People started coming, and the program became very large. We established a great network from these experiences, networks people still work with. Sandra Laronde [artistic director, Red Sky] was there then. She'd just started to dance; she was an actress and came to the program. Carlos, from Red Sky, we invited to come from Mexico. Santee Smith was there, and Penny Couchie. Many singers and dancers and actors, too, passed through the program. They are out there working. I'm proud of them – I think of them as my “kids” – they are out there as choreographers and directors and dancers. You're working sooner than you think you will – so this was about providing tools. AR: I worked at Banff seven years. The legacy is there – there's still a funded program. They run a summer program. It's a different shape and form; it's been re-invented, as it should be. My motivation at the time I was there was that I needed dancers, and this was the time and place to do it; so they came in to a six-week learning process, and we had a presentation. It paid off. The participants learned new skills and traditions. It was very, very demanding. At the same time, I was training choreographers – my whole idea was that we need to train choreographers and designers; we need composers, everyone, to grow capacity. Also my agenda contained the need to reach out internationally. So we did – to Mexico, Colombia, New Zealand, Australia, the U.S. People started coming, and the program became very large. We established a great network from these experiences, networks people still work with. Sandra Laronde [artistic director, Red Sky] was there then. She'd just started to dance; she was an actress and came to the program. Carlos, from Red Sky, we invited to come from Mexico. Santee Smith was there, and Penny Couchie. Many singers and dancers and actors, too, passed through the program. They are out there working. I'm proud of them – I think of them as my “kids” – they are out there as choreographers and directors and dancers. You're working sooner than you think you will – so this was about providing tools.

I started noticing a lack of literacy among choreographers. I started thinking about my own formation – when I was in New York, I'd go to Lincoln Center Library two or three times, pulling out archives to watch fantastic performances from all over the world, and pieces by Limón, Balanchine, Ailey and other great choreographers – I learned through exposure to the greats, the masters. I felt there was a disconnection among younger choreographers, and too often people rush to the stage without an outline, a throughline, real research. From my theatre experience I knew you have to find a throughline; you create a script, you clarify your ideas and then you go into the studio to create. You have to do the homework. From my theatre experience, and my own choreographic and performance background and study, I made my own methodology putting together choreographic workshops. I did my first one in 1995 in Mexico City – and there were important choreographers there, big names, ten choreographers! It was intimidating, but it was also the glory days! They got used to that process of workshopping ideas – I made them write ideas with three scenes and write the scenes – they had to participate in that process. I could see influences from Pina Bausch, or from the opera, in their work. That was quite interesting – everyone did their five-minute piece at the end. I called the showing Genesis. Five of those pieces subsequently became successful major works. I took the idea to Banff and said, “I want to give a choreographer's workshop, where we provide tools.” Unfortunately, that had not yet been taught. In Mexico, by contrast, there was an established mentor-master situation, like painters or musicians, that kind of tradition. But here there was nothing. We basically, historically, were going from heavily scripted ballet to the unknown – a free-for-all! And indulging: I do what I want, and you take it or you leave it … It's important to keep going back to the basics – if you know structures, know how to create a throughline, you save a lot of time. This is so important, especially when you don't have a lot of resources, a big budget or a lot of time. You do have to do your homework before going into the studio process. It's always healthy to ask someone from outside to help to do that work with you, so you can be more objective. At a certain point, I decided to step back, as there was too much to do to keep performing. I was performing a lot, and having a great time, but needed to step back, to be more the objective eye. I saw that Pina Bausch knew the trick – she did the solos and everyone else did the corps work. Then I saw Susanne Linke. She's fantastic; I have so much respect for how she can carry the work and hold an audience. That's when I decided to do more solo work. My whole idea has been to create a movement, to explore the rich traditions of dance in North America. Sometimes it's really opera, or oratorio, if you look at the way that tradition and ceremony is presented. Connection to tradition has been carried forward by René, by Tomson Highway, Raoul Trujillo, Michael Greyeyes. We all see things through different artistic lenses, representing our individuality and our own traditions within the bigger picture. It's happening in dance, in song, in film, in theatre. (next page) | |