|

next page l previous page CA: Why did you come back to Canada? LP: I came back to Canada on annual visits to perform and tour across Canada and the US with my guru and orchestra. I bought myself a house in Mississauga so that I would have a base. But each trip reminded me how much I missed Canada, my friends and being part of the artistic scene here. On my intermittent visits, so many friends tried to persuade me, “We'd really like you to come back and teach. We'd love for you to be part of the community here.” I guess that was what prompted the desire to return. I felt increasingly pulled back to Canada and despite the fact that I was performing in India extensively as a soloist and as part of my guru's productions, in 1990 I returned to my home in Mississauga.  I knew, at the age of forty-three, that I could continue to be a performer, but my yearning to teach, to transfer what I had gained, was uppermost in my mind. So I started teaching in the basement of my home in Mississauga and established Sampradaya Dance Academy. My solo performances were part of my company, Sampradaya Dance Creations. Soon I was actively performing and creating new work for my students. Many of them had come with previous training in bharatanatyam, so it was just a question of adapting their technique to the style that I had trained in and enhancing their performing skills. There were many opportunities to showcase our work. I knew, at the age of forty-three, that I could continue to be a performer, but my yearning to teach, to transfer what I had gained, was uppermost in my mind. So I started teaching in the basement of my home in Mississauga and established Sampradaya Dance Academy. My solo performances were part of my company, Sampradaya Dance Creations. Soon I was actively performing and creating new work for my students. Many of them had come with previous training in bharatanatyam, so it was just a question of adapting their technique to the style that I had trained in and enhancing their performing skills. There were many opportunities to showcase our work.

In Mississauga, the need and demand for bharatanatyam training was evident, as was the imperative for vocational training. At that time, Indian dance was still seen as a community practice … CA: That was at a point of change; 1990 was the year of the report to Canada Council, written by Susan Macpherson, on “Other Forms” of dance besides ballet and contemporary concert dance. An important time. LP: The needed shift toward a new direction. CA: Susan's report was a watershed; people at the Council began to open their perspectives and realize – particularly in the case of Indian dance – that this was not folk dance, but classical art …LP: Yes, a legitimate art form, with a prescribed and very sophisticated vocabulary that demanded the rigour of long, intense training. Interestingly, my own experience with grant-writing and being part of that funding stream had already started with the touring grant and professional development grant I had been awarded by the Canada Council. Certainly, after 1990 I began to see a far greater degree of openness and receptivity to the notion of Indian dance being eligible for funding. But while there were grants for dancers to create new work, or to travel to India to commission music, or work with a collaborator, Indian dance was still not being seen on the main stages.A seminal event for Indian dance occurred in 1993. Started by Sudha Khandwani, the Kalanidhi Festival was titled New Directions in Indian Dance. The festival was a major international event, where many dance scholars and practitioners gathered, companies from India were invited to perform. It created a huge momentum for Indian dance. Sudha was able to produce the festival on a scale that propelled Indian dance into the public eye.  CA: Is it fair to say Kalanidhi changed the perception of the GTA as an international centre for Indian dance? CA: Is it fair to say Kalanidhi changed the perception of the GTA as an international centre for Indian dance?

LP: Yes, absolutely. Many funders, choreographers and artists from the non-Indian community were at those performances, workshops and panel discussions. Sudha had strategically invited people who could speak about Indian dance. They came with so much knowledge and authority – I think it really did change the perception. The mainstream was beginning to understand that this was not some exotic, museum-piece art form. For some of us, risk-taking was very much how we imagined our dance; we were committed to expanding our minds and artistic horizons in some of these experimentations we were creating. But to the arts councils, committees and juries, at first, as long as it looked and sounded like Indian dance, then it was traditional … and where was the innovation, where was the newness of the work? That was the difficulty we faced for a long time. As a jury participant, I know what the discussions were. If you saw video excerpts of something that looked Indian, then some jury members had a hard time wrapping their minds around where the experimentation was. But I think going back to school at York University was what really catapulted me into a different world. CA: That was through your connection with Selma Odom? [York University Professor Emerita Selma Odom] LP: I met Selma at one of the Kalanidhi festivals. She said, “You have a world of experience, you're a practitioner, a teacher and choreographer – and you have a certain vision – so let's talk about a graduate degree.” It was a completely new world … a world where I looked at the place of bharatanatyam within world dance traditions in order to investigate the socio-political and cultural-historical interruptions in the narrative of bharatanatyam.CA: This was your thesis work?LP: My thesis work was actually looking at how I approached the creation of new work – the analysis of developing a contemporary voice while being rooted in classic bharatanatyam. I've always existed in these two worlds – one where my complete reverence and desire is to celebrate the classical form, which I honour very deeply, and the other – my search for a new way for expressing the art in the “here and now” of being a Canadian artist. While bharatanatyam found its moorings in the “diasporic” culture in Canada, there were many transnational intersections happening at the same time across the world. Bharatanatyam was very much an active player in global circulation and expression of local identity. It gave me a new perspective to “witness” my own dance form.  CA: What years were these? CA: What years were these?

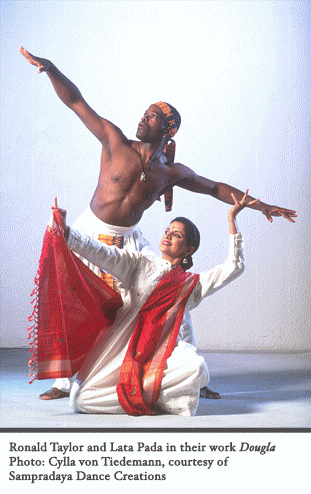

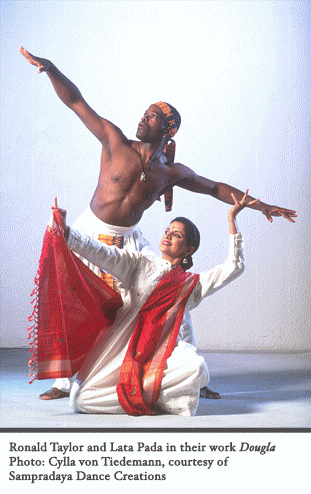

LP: I was at York from 1994-1996. A very busy schedule juggling so many roles – developing my academy, teaching, coping with university, learning to be part of the larger dance community, creating and presenting new work – and at the same time, dealing with the aftermath of the Air India tragedy … I was developing a different persona in my activism for finding ways of pushing for a public enquiry. Increasingly, I knew that the only way I could have a dance company of excellence was to be rooted in the training I would provide my dancers. There was a richness developing in the 1990s. I created several small works and started collaborating with artists like Ronald Taylor. We did a work called Dougla – inspired by Trinidadian culture that is infused with Indian culture. Then I collaborated with Mi Young Kim and Elena Quah, and with Carmen Romero in a work we called Charla. I commissioned Trichy Sankaran of York University to create an original score for Timescape and toured that work across Canada. An invitation came to apply to the Equity Office at the Canada Council for special funding for capacity-building of culturally diverse dance. The opportunity through that grant was to employ an in-house company administrator. This was for multiple years and it was hoped that afterward the company would be on its feet and be able to sustain itself. That was an important turning point for the company. I was still operating out of my home. In 1999, I had a conversation with [photographer] Cylla von Tiedemann about a possible collaboration on a new work. Cylla has a deep connection to India and had journeyed there a few times. We travelled to India together to research and develop our ideas, and through our travels over six weeks, the nature of the work shifted several times. But I knew that it had to be woman-centric. There was a lot about my own personal experience, my own questioning from my days as a young woman, about the role of women in society in India, the seemingly incongruous relationship between the reverence and honouring of goddess figures in our culture and, on the other hand, the complete denigration of women. At that time, the role of multimedia in dance was less pervasive. Cylla is a brilliant photographer – I thought, “How lovely to look at the very beautiful nexus between dance and architecture in India.” So emotionally I was going toward the woman-centric ideas, while artistically, we were looking at temples and architecture. Cylla, sensitive artist that she is, began to see that those paths were divergent. We were not coming to any kind of congruence. One day, she said, “Why don't you tell your story? Why can't this be about you? About you and what you've gone through.” I was terrified; “That's a personal story. How can I tell that onstage?” CA: A personal story would be very un-traditional?Excerpt from Revealed by Fire

LP: Yes, very untraditional – certainly as far as something I would do, or had experienced. A deeply personal work felt uncomfortable. So we talked – and that was a Eureka moment for me. Cylla said, “There's no way we cannot weave your own story with your personal journey toward reconciling some of those things that have been bothering you for a very long time.” And that is how Revealed by Fire was born. (next page) | |

I knew, at the age of forty-three, that I could continue to be a performer, but my yearning to teach, to transfer what I had gained, was uppermost in my mind. So I started teaching in the basement of my home in Mississauga and established Sampradaya Dance Academy. My solo performances were part of my company, Sampradaya Dance Creations. Soon I was actively performing and creating new work for my students. Many of them had come with previous training in bharatanatyam, so it was just a question of adapting their technique to the style that I had trained in and enhancing their performing skills. There were many opportunities to showcase our work.

I knew, at the age of forty-three, that I could continue to be a performer, but my yearning to teach, to transfer what I had gained, was uppermost in my mind. So I started teaching in the basement of my home in Mississauga and established Sampradaya Dance Academy. My solo performances were part of my company, Sampradaya Dance Creations. Soon I was actively performing and creating new work for my students. Many of them had come with previous training in bharatanatyam, so it was just a question of adapting their technique to the style that I had trained in and enhancing their performing skills. There were many opportunities to showcase our work. CA: Is it fair to say Kalanidhi changed the perception of the GTA as an international centre for Indian dance?

CA: Is it fair to say Kalanidhi changed the perception of the GTA as an international centre for Indian dance?  CA: What years were these?

CA: What years were these?