|

next page l previous page  We came back to Canada with many beautiful and evocative images and the seeds of a new work. Interestingly enough, it was in 2000 that the arrests were made of the two main masterminds of the Air India bombing. I had my own qualms and misgivings, thinking, “Oh my god, this is now propelled into the public domain, and how can I tell my story, which is also related to the Air India bombing.” Another very important person came into my life at that time – Judith Rudakoff. Her dramaturgical skill and her very sensitive understanding of what I was trying to say put all the pieces of my own questioning, my story, into play. Suddenly it seemed to fit, and Judith was the one who brought all that together. We came back to Canada with many beautiful and evocative images and the seeds of a new work. Interestingly enough, it was in 2000 that the arrests were made of the two main masterminds of the Air India bombing. I had my own qualms and misgivings, thinking, “Oh my god, this is now propelled into the public domain, and how can I tell my story, which is also related to the Air India bombing.” Another very important person came into my life at that time – Judith Rudakoff. Her dramaturgical skill and her very sensitive understanding of what I was trying to say put all the pieces of my own questioning, my story, into play. Suddenly it seemed to fit, and Judith was the one who brought all that together.

Judith crafted very beautiful text – created from my own reflections – they were recorded and became part of the soundscape. The whole notion of being a widow in India is inauspicious. Societally, there are nuanced behaviours that suggest you are not welcome in certain places. That happened to me on many an occasion when I was in India.There was also a very important motif in the work, which was the ring of the telephone. The deathly chill of that first ring that told me of the terrible bombing was the recurring motif in the soundscape. That seems to be, for me, my seminal creative work. It took an immense amount of courage. I had to learn to face the potential ostracization of my community – in the diaspora, people who have a very old-world notion of what Indian dance in Canada should be. Revealed by Fire would turn that notion on its head.CA: So you were concerned both about what you were saying and the form in which it was expressed?LP: Actually, it was as much about my story as about the liberty I had taken of the form. Revealing the trauma of personal grief and exposing the hypocrisy of what is seen as auspicious was going beyond the boundaries of traditional repertoire. It was about stripping me of all things auspicious now that I was a widow. The kumkum [red mark] on my forehead, the bangles and the wedding chain, all a part of the wedding rituals were now to be removed. I questioned, how does that change who I am, why does that render me inauspicious? Is my true identity now altered forever? The text in the work asks, “If my husband dies, am I still a wife? When my children die, am I not still their mother? Who am I?” It was a potent question. Revealed by Fire was transformative; in the telling of my story something had shifted. Willing movement back into my body after it had been shattered, baring my inner world in public, I found new meaning in dance. Another turning point was taking this work to India. I toured with Revealed by Fire in five cities in India.CA: Where are we in time now?LP: It was 2003. Revealed by Fire co-incidentally – or it was destined to be? – opened on International Women's Day, March 7, 2001, at what was then Premiere Dance Theatre. We also produced a display of women visual artists in the foyer of the theatre.In 2003, touring to India, I was anxious about how India would be receptive to the work. I needed to remind myself that India was a progressive country, surging forward to its place on the global map. Indian society had come of age, women's voices had legitimacy. The response was overwhelming. I have a huge binder of all the reviews and publicity material. I just could not believe the success of that work. Probably the biggest test was performing it for my guru. He generously sponsored and presented my performance in Bombay. I shared with him, with great trepidation, that Revealed by Fire was unconventional. With tears in his eyes, he said, “Don't ever be afraid.” That's what he said – he didn't say how he liked the work. We had 800 people in the theatre.My guru had been part of my own journey … he travelled on both my tours across North America – he and his wife lovingly cradled me at the time of this tragedy – and gave me new life. He rightfully felt that he had invested in my emergence from this dark chapter. I remember that today in my own bond with my students. If I can help them find their own voice and inner strength, then I know that I have prepared them for what life might unexpectedly present to them.

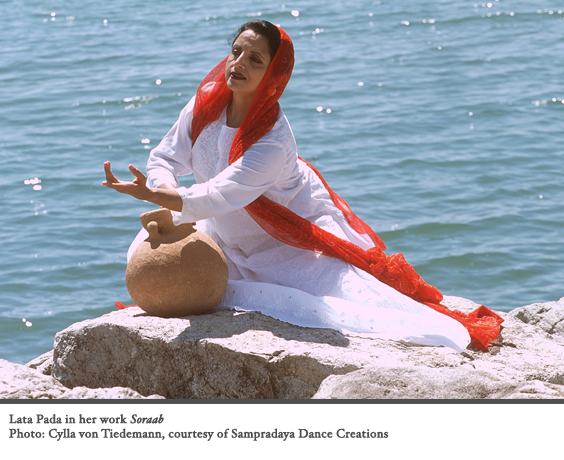

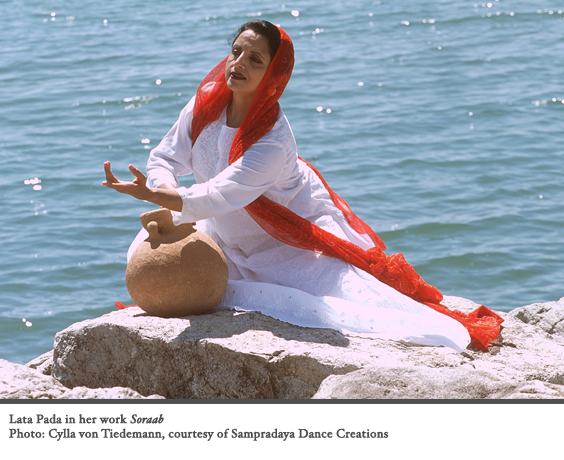

That is important for me. In 2002, I created a new work called Soraab, about the plight of an Afghan woman. I then created a work called Cosmos – it was a contemporary work, rooted in classical bharatanatyam, no text, no personal narrative. This was a collaboration with Canadian composer Timothy Sullivan and Ravi Kiran, a very well-known Indian composer/vocalist, renowned for his mastery over an instrument called a chitravina. Many new works followed. CA: Some of your journey has been into the bravery of collaboration …LP: Very much so. Remember, in the 1990s and early 2000s, the word “fusion” was being bandied around quite a bit … I must confess that I myself was part of that trend in a couple of works, but was uncomfortable with that process. I felt the process for finding common ground was at surface level. I began to see that collaboration was a far more risk-taking, organic undertaking, a level playing field, where artists negotiated to work with difference but find convergence in shared values.Excerpt from B2

Yes, and without losing the integrity of that form. B2, our collaboration with Ballet Jörgen, was an important project. I suggested England's Mavin Khoo, who is both an accomplished ballet and bharatanatyam dancer, with an incredible duality in his body. It was a truly enriching experience for the dancers, Bengt and myself. Brian Webb, then artistic director of the Canada Dance Festival (CDF) was excited by our early work and gave us commissioning support to present it at the 2008 CDF. So B2 was one of those earnest and honest desires to look at two forms coming together, in the expert hands of Mavin Khoo.Equally interested in exploring Chhau, derived from an Indian martial form, I invited Santosh Nair from New Delhi, India, to work with our dancers, leading to the creation of Stealth with commissioning support from the Canada Dance Festival.

I was intrigued by the intercultural nature of working with other dance forms and traditions. That led to Samvad (Sanskrit for dialogue) with Michael Greyeyes, Charmaine Headley and myself. We mentored three emerging choreographers through a process of open dialogue. Each had a deeply personal story to tell – we showed them the tools to find the clarity and courage to tell it. Margaret Manson, an educator, found the intercultural experience and that process of discovery very interesting; she applied for a SSHRC grant, in which Charmaine and myself were collaborators. The project was entitled "Intercultural performance practices in dance and their influence on emerging practices of arts-based intercultural teaching and learning in inclusive classrooms". Charmaine and I have worked with Margaret on the SSHRC project for the past two years. We have assisted in demonstrating dance as not just a technique but as a cultural way of knowing – the body as a tool to communicate difference and commonality.There's a whole other part that I would like to share – Sampradaya Dance Creations broadening its mandate into a South Asian development organization. It's a model that I had seen happening in England. CA: You've been there numerous times, yes?LP: Yes, and I have many peers with whom I stay in contact, and I've attended several conferences in England. In 2003, I received a research grant from Canada Council to look at how Indian dance companies, artists, support services, dance development organizations function; England is very vibrant and forward thinking. This research led to a feasibility study, with Ellen Busby as a consultant, to see whether Sampradaya had the potential to broaden its mandate so that beyond being a creation/production company, it could start being a catalyst for providing opportunities for growth in the South Asian dance community. Fortunately, we had wonderful collaborators in England … which has had a very strong history of arts education. Artists from all disciplines were able to have a career in both performance and arts education – enough work to make a complete living from their practice. These arts development organizations were the catalysts for providing professional development, opportunities for emerging artists, commissioning new work, creating festivals. (next page) | |

We came back to Canada with many beautiful and evocative images and the seeds of a new work. Interestingly enough, it was in 2000 that the arrests were made of the two main masterminds of the Air India bombing. I had my own qualms and misgivings, thinking, “Oh my god, this is now propelled into the public domain, and how can I tell my story, which is also related to the Air India bombing.” Another very important person came into my life at that time – Judith Rudakoff. Her dramaturgical skill and her very sensitive understanding of what I was trying to say put all the pieces of my own questioning, my story, into play. Suddenly it seemed to fit, and Judith was the one who brought all that together.

We came back to Canada with many beautiful and evocative images and the seeds of a new work. Interestingly enough, it was in 2000 that the arrests were made of the two main masterminds of the Air India bombing. I had my own qualms and misgivings, thinking, “Oh my god, this is now propelled into the public domain, and how can I tell my story, which is also related to the Air India bombing.” Another very important person came into my life at that time – Judith Rudakoff. Her dramaturgical skill and her very sensitive understanding of what I was trying to say put all the pieces of my own questioning, my story, into play. Suddenly it seemed to fit, and Judith was the one who brought all that together.