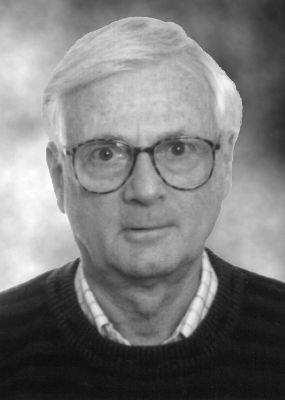

LELAND WINDREICH

MARCH 2010

DANCE HISTORIAN OF THE MONTH

INTRODUCTION

Welcome back to “Dance Historian of the Month,” where the hope is to illuminate something about the person, their craft, the field, and to provide a peek into what inspires those uncovering and rediscovering our dance pasts. As has been revealed in our previous interviews with Selma Odom, Allana Lindgren, Vincent Warren, Lisa Doolittle and Max Wyman – there is no one way into the field of dance history/writing/researching/curating; and once in, the path is not delineated – its end goal is only the open window of discovery.

This month’s interview is with writer, critic, historian and librarian Leland Windreich. Originally from San Francisco and raised during the Depression era, Windreich’s early exposure to dance included seeing the Ballets Russes and American Ballet Theatre in the 1930s and 1940s. Later on, encouragement from his pen pal Agnes de Mille inspired him to write about dance even though it was not a financially promising endeavour.

Brought to Canada in the early 1960s by an administrative library position at University of Victoria, Windreich found himself in a place that was also the hometown of a group of young dancers who received exceptional training from Vancouver teacher June Roper during the 1930s. These students all made their way from Vancouver Island to international stages as Canada was just beginning to form its own ballet companies. Windreich has completed two book projects about this special group: he edited Dancing for de Basil: Letters to her parents from Rosemary Deveson 1938-1940 (1996), and wrote June Roper: Ballet Starmaker (1999). He also compiled a selection of his writings called Dance Encounters (1998). All three books were published by Dance Collection Danse Press/Presse. He has also written extensively for dance publications including Dance in Canada Magazine, Dance International and Dancing Times, among others. He counts three to four hundred critical and historical articles in his portfolio.

During my conversation with Lee, as he is known to friends and colleagues, I was struck by his humour (a trait he has been noted for throughout his career) and his boyish enthusiasm for everything from his lifelong interest in the Ballets Russes to a new discovery of pop icon Marianne Faithful. It reminded me that at the heart of all critics’ work, no matter how sharp their tone in print may be, is a tender, tender love for the art form of their focus.

Enjoy the interview.

Seika Boye

INTERVIEW

Name: Leland Windreich

Date of birth: September 10, 1926 (Died July 29, 2012)

Place of birth: San Francisco, California

SB: What was your path to becoming a dance historian?

LW: I first saw the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo at age fourteen.

SB: Had you been exposed to dance before this?

LW: I’d seen the crummy things that kids do at recitals. My exposure was largely films. I grew up in the Depression and we could see a movie for a nickel or a dime. My mother liked the movies. I liked the actress/dancer Eleanor Powell. Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers and those sorts of people were in the movies we saw too, but Eleanor Powell was my idea of heaven.

My mother enjoyed opera very much and there was a company that toured the United States at the time called the San Carlo Opera. They were second string and not very luxurious but they sang pretty well. Every year we saved up a dollar to go. Can you believe that, a dollar? We saw Carmen first and thought it was great, then Faust and Rigoletto. The big sensation was Sampson and Delilah. It was very exotic, lots of hands twisted sideways in the Egyptian motifs. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever seen.

About that time, I was fourteen or fifteen, my mother and I were looking at a program during intermission and saw an ad for the The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo who were coming in a month. It is as if it happened yesterday. My mother said, “Why don’t we go to see this? We can get a dollar ticket. It’s all dancing, there’s no voice, no talking stuff – it should be fun.” They were performing Leonide Massine’s Gâité Parisienne. It was the decision that changed my life.

I didn’t know anything about anything. I had seen Max Reinhart’s film A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Mickey Rooney was Puck; there was a whole cast of popular Warner Brothers actors and actresses, most are probably dead now. There was a ballet in the film by Bronislava Nijinska – I didn’t have any idea of who she was then. It was an abstract ballet with fairies and elves running through a beautiful landscape. The whole movie was a gorgeous thing, like a child’s dream. There was a dancer named Nini Theilade who appeared in the documentary Ballets Russes (2005), she was The Queen of Fairies. She was adorable and quite small and she ran through the forest looking beautiful. The ballet is not formal, there is no focus, just fairies running and jumping. It was the first ballet I’d ever seen. I never forgot that.

SB: When you saw the Ballets Russes perform in the theatre what struck you? What about it changed your life?

LW: It was everything that I thought should be.

I remember the program. They danced Les Sylphides with Mia Slavenska and Alicia Markova, and Rouge et Noir, a Massine ballet, which was extraordinary – it has never been revived because the film of it was destroyed. Spectre de la Rose and Gâité Parisienne completed the program. That was my introduction.

SB: That’s quite an introduction.

LW: It was just extraordinary. I remember coming out and thinking, opera gets boring sometimes because of the talking, and it seemed to me that dance and the body did so much more in conveying what things were all about. It was sexy too. Not flagrantly, but the relationships from Gâité Parisienne for example were just ecstatic. The whole thing was ecstasy more than anything else. It was wonderful music. It was all of the things I was becoming aware of as an adolescent. The company came back later and I managed to get another dollar. We saw Le Tricorne, The Magic Swan, which was the third act of Swan Lake, and L’Après midi d’un faune.

SB: How long was it between the two performances?

LW: It was about six months. It was wartime and there was nowhere to go so they did a double American tour. The next group came in 1943, it was American Ballet Theatre who was then Ballet Theatre and it was in its second year. There were three premieres every night, things we had never seen. It was just incredible. I was paralyzed with joy. A lot of things I have dealt with in my writing came out of that year. I wrote a piece on Massine’s Aleko. It was a Marc Chagall production – he painted the sets himself. In these early years I was introduced to things and people I had never heard of before and became smitten by them. There was a lot to stimulate one in those days. By then, getting a dollar together was becoming a problem so I became an usher and for the next six years I saw everything that came through the San Francisco Opera House – dance, opera, symphony – the whole shebang. It was a very rich era to be living in.

Around that time I wanted to be a writer. I thought I’d be a great novelist. It turned out that I didn’t have the capability of putting imaginary situations together, but I did very well in literary criticism. While I was studying at University of California, Berkeley, I always received very good praise from my professors and one of them, who was a published poet, Josephine Miles, said, “You might consider being a critic. You have humour, your pieces are very funny to read, and so many going into criticism are terribly dry and unfunny.” I wrote for some of the college publications.

I was out of college at nineteen and I didn’t know what to do with myself. For the next several years I worked in offices. I wrote book reviews for the San Francisco Chronicle but I didn’t really get to write about dance until I came to Canada.

SB: Why was that?

LW: There was no market for it. There was Dance Magazine and a tabloid paper called Dance News, but they didn’t pay then. Dance Magazine gave an honorarium of $25. Mom said, “You shouldn’t give work away for free, you have to support yourself.” Which is correct! I finally wrote an article for a regional magazine and received $75. It was about American Ballet Theatre’s 1945 season but they never asked me back and I didn’t establish any contact with them. I had two criticisms printed in Dance News in New York City. They were reviews of the San Francisco Ballet. After that there wasn’t much of anything for a long time.

Eventually I went to library school. I had to do something because I was living in dumps. I was having a good time for a young person, but I couldn’t figure doing it for the rest of my life. Library school was a means of getting a job in an area that I thought I’d be reasonably content in. I became a music librarian, which was all right except that the people I was working with were old ladies, there were not many men. One of the reasons I decided to work in the library system was that right after the war there was a change in the concept of occupations for men. The big city libraries wanted to get men in as administrators. They maintained that women weren’t any good. I hated the sexism and the rigid attitude of how people were expected to behave. For the next thirty-seven years I was a librarian.

SB: Is work as a librarian what took you to Vancouver?

LW: Yes. I saw an ad in a library journal for a department head position. By then I was pretty well experienced and the idea of coming to Canada appealed to me. I didn’t know anything about it. It was a foreign place. I took the position at University of Victoria in 1961. I made some wonderful friends, there were more people my age and we had lots of fun. I was amazed that the work ethic was so much lighter than in the U.S. – 100 percent lighter. I would ask someone to do something and they’d say, “I’ll do it when I’m ready.” If you said that in the U.S. you would be out the door! I liked Canada so much better that I stayed here. I have spent half of my life in Canada. Over the years I also worked at University of British Columbia, Toronto Board of Education and Vancouver City College. I retired in the early 1970s.

SB: Where did criticism fit in at this point?

LW: Many years earlier I had written a letter to Agnes de Mille. I just loved her. She was really quite adorable, but she was also a wretch, just the meanest person. I saw her behave in ways I could not believe. Anyway, I wrote her a letter in response to an article she’d written for Harper’s magazine about Alicia Markova. She wrote back almost immediately and we developed a pen-pal relationship. She came up to lecture at the local hotel in Nanaimo – it was part of a public lecture series. I met her and we kept connected over the years. She encouraged me, told me I wrote very well and that I should be writing for a newspaper. It meant a great deal to me. I knew by that time that I wasn’t going to make any money but decided I would go ahead and write anyway. By this time there were magazines coming out that offered criticism. It was then that I became interested in history. I think I really felt spiritually connected to the field of criticism.

Then a particular situation came up in my life. I had moved to Victoria and I went back to San Francisco to see mother. A local branch library there had opened a dance department to cater to the large interest in ballet that had developed. I talked to the librarian and she suggested that I should be writing about dance history, that Victoria is full of it and to look through some of the old magazines when I returned. There were not many indexes then, but she told me that there was a marvelous boy named Ian Gibson who was a phenomenal dancer and he had had a fantastic teacher who was a Texan. So I looked them up, the teacher’s name was June Roper and there was, indeed, a history. Both of them were internationally known. I started looking in the city archives for resources, but there wasn’t much in terms of ballet history. I found that there were eight dancers in total who had ended up in ballet companies of the time. I thought, isn’t that remarkable, from this pokey little town. I was beside myself with joy. I spent the next few years doing research. I discovered a considerable amount. I contacted Canada Council and applied for money to find these people and write about them.

I was very shy and modest in those days, it was 1978 and I only asked for $2000. I crossed the country, went to San Francisco. I made good friends with Jean Hunt Haet. Ian Gibson had disappeared; he was a J.D. Salinger-like figure. He had left dance and didn’t want any part of it. I guess he was ashamed that he wasn’t able to dance anymore after the war; he’d lost his technique after living in a submarine. He became a very successful executive in a taxi company. I made every effort to contact him but he never answered. Then June Roper popped up in Vancouver. I asked her about Ian and she told me he was in Alpine, New Jersey. She connected with him and he was divinely happy to hear from her and said, “If you come east I’ll make a point to come and see you.” That broke his silence. I did a piece for Dance in Canada and made two good friends without any effort.

Roper’s students were Rosemary Deveson, Duncan Noble, Robert Lindgren, Margaret Banks, Audree Thomas, Patricia Meyers, Ian Gibson, Jean Hunt. They all had experience in the Ballets Russes. If you can imagine what Canada was like in 1935-1936, and these children who wanted to be ballet dancers had never seen any ballet. They all ended up in touring companies with good assignments. In a way they were as smitten as I was as a spectator. They were all from poor families and gave up high school. They were so dedicated. I still think it’s remarkable.

When June Roper had settled back in Vancouver, she invited Rosemary Deveson, two or three others and myself to lunch at her house. I loved them all and am still in touch with the ones who are alive.

I always felt, when I found out about these eight dancers, that I had hit on something magical and I really milked it – I wrote about them from every perspective. I found out about their careers or lack thereof. It gave me a great deal of respect for them. Each one was fascinating. In those days I don’t think that people were so desperate to get out of their communities. They had to be pretty good to accomplish what they did. Eight Canadian kids who weren’t very well educated and who didn’t have any experience with the art form, except in the studio, made it into major companies at a time when there was very little happening in Canada.

SB: It sounds like it was very serendipitous. Were you doing any other writing in addition to this research?

LW: In 1978 the Dance in Canada Association hosted its first west coast conference. There I met Michael Crabb who was the editor of the Dance in Canada magazine; he was desperately looking for writers. He gave me a trial run and I wrote for the whole length of his tenure. I covered anything current in British Columbia. He too was very encouraging. He asked me where I learned and I told him I had disobeyed my parents! I didn’t stay home and do the dishes I went to the ballet instead! From then on people began writing to me asking, ”Can you do this? What do you know about so and so?” Dancing Times editor Mary Clarke contacted me and I started working for her too.

A big triumph in my career was attending an intensive workshop at the American Dance Festival’s Critics’ Conference at Duke University, North Carolina, in the early 1970s. I thought I didn’t stand a chance of being accepted, thought “I’m nobody”, but applied anyway and got in. I was there for three weeks and it was one of the best experiences I had in learning how to write and how to present my writing. Deborah Jowitt was the main teacher. She read our first assignment aloud in class and when she read mine she said, “This is very funny!” Then she said, “The next time you look at a performance, don’t tell me how you felt, tell me what you saw.” This had never occurred to me … in two or three hundred years from now what the reader will appreciate is a good word picture, not a description of the writer’s feelings.

One of my favourite writers, Nancy Goldner, was also there. She wrote a book called The Stravinsky Festival of The New York City Ballet (1973). She has lectured throughout the country and goes to communities where they are doing Stravinsky’s work. She’s the nicest person and she likes jokes. Her work is buoyant with fun. It makes you comfortable.

SB: What are you reading right now?

LW: I was most recently reading Lincoln Kirstein: Program Notes 1934-1991 (2008). I don’t read all that much any more. I watch DVDs.

SB: What have you watched recently?

LW: I just finished Jerome Robbins: Something to Dance About – The Definitive Biography of an American Dance Master (2009), which was divine. It was very comprehensive, with all of the warts and everything else but very well done and very tasteful.

SB: Why DVDs over books?

LW: I spend a lot of time at home. I lost interest in reading about two or three years ago. It is largely because of my eyes; I came down with shingles and never got rid of it.

Now I watch fiction and a lot of foreign films – there are so many that we don’t know about. I just watched one called Irina Palm (2007), starring the musician and actress Marianne Faithful. It is about a widowed housewife looking for money to pay for a cure for her dying grandson. She sees a Hostess Wanted sign in the window of what turns out to be a sex “shop” and she ends up taking the job and befriending the sleazy manager. It was very good. I googled Faithful and was amazed to learn about all of the people she is connected to. It opened up a whole new world that I knew nothing about.

I also like taking out movies from countries I know nothing about. On the same visit to the library I found another film called The Band’s Visit (2007) about an Egyptian musical band that goes into Israel to play at a celebration. I don’t usually like Middle Eastern movies, but this was agonizingly funny, just marvelous.

SB: If you could travel to an era of the dance past where would you go?

LW: I would like to have lived in the Diaghilev era, 1909-1929.

SB: Any specific period within that era?

LW: May 13, 1913. Everybody wants to be there. A movie is coming out soon called Igor and Coco about Coco Chanel’s affair with Igor Stravinsky. It starts with Coco walking into Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on the evening of Le Sacre de Printemps premiere, not knowing what to expect. Later on they met socially and she invited him to move into her house. It sounds good.

SB: Do you feel that you have any work left undone?

I don’t think so. At this point I figure I have somewhere between three and four hundred history and criticism pieces in print. I think that somewhere along the way I ran out of history ideas. I don’t like to muck around with anything I’m not 100 percent familiar with. I do love reviewing dance books. If I get a book to review I’ll do it, though if it is not any good I won’t bother with it. I’ve got a small pile of books that have been sent to me.

SB: Anything exciting?

Kirstein’s Program Notes is a good one to have. He starts in the beginning, with the origins of The American Ballet in 1934. He wrote all of the program notes over the years. Here on the west coast we’ve had great contention over the years about the need for program notes. I think the absence of them alienates audiences who are invariably bewildered by dance. Notes don’t do any harm.

There is also a beautiful book called The Ballets Russes and the Art of Design (2009). It is absolutely ravishing. I am personally very interested in the visual aspect of dance.

I also have some videos: Divine Dancers: Live from Prague/Prague State Opera (2006); Art of the Pas de Deux, Vol. 2 (2006); Prokofiev – The Stone Flower (2005)

Books can’t talk back. I like that!

PUBLICATIONS

- Dancing for de Basil: Letters to her Parents from Rosemary Deveson, 1938-1940 – Edited by Leland Windreich (Dance Collection Danse Press/es)

- June Roper: Ballet Starmaker – by Leland Windreich (Dance Collection Danse Press/es)

- To read Gay Jackson’s obituary in the Globe & Mail for Mr. Windreich, CLICK HERE

- The Ballets Russes Archives at the University of Okalahoma School of Dance holds a collection of his books, articles and digital photos. CLICK HERE to view its contents

PERSONNEL

Miriam Adams, C.M.

Co-founder/Advisor

Amy Bowring

Executive and Curatorial Director

Jay Rankin

Administrative Director

Vickie Fagan

Director of Development and Producer/Hall of Fame

Elisabeth Kelly

Archives and Programming Coordinator

Michael Ripley

Marketing & Sales Coordinator

CONTACT

1303 – 2 Carlton St.

Toronto, ON

M5B 1J3

Canada

Phone: 416-365-3233

Fax: 416-365-3169

info [AT] dcd.ca

HOURS

Mon. – Fri. 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Appointment Required

Contact our team by email or call one of the numbers above