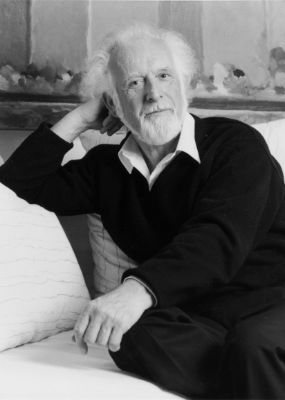

MAX WYMAN

JANUARY 2010

DANCE HISTORIAN OF THE MONTH

INTRODUCTION

Welcome back to “Dance Historian of the Month,” where the hope is to illuminate something about the person, their craft, the field, and to provide a peek into what inspires those uncovering and rediscovering our dance pasts. As has been revealed in our previous interviews with Selma Odom, Allana Lindgren, Vincent Warren and Lisa Doolittle, there is no one way into the field of dance history/writing/researching/curating; and once in, the path is not delineated – its end goal is only the open window of discovery.

This month’s interview is with Max Wyman: writer, critic, editor, cultural commentator, arts policy consultant, politician (he was the Mayor of Lions Bay, BC from 2005-2008), Officer of the Order of Canada, former president of the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. And, he has a star on British Columbia’s Walk of Fame. Wyman, it is safe to say, is a celebrity of arts writing in Canada. He is the author of the first – yes, the first – Canadian dance history book, Dance Canada: An Illustrated History (1989) and has published a number of other books (see a full list following the interview). Today he is working on revisions for his first novel. “I find all writing quite wonderful,” he comments in our interview, “It is what I do.”

Wyman is the first Dance Historian of the Month featured who is neither an academic, nor a retired dancer – he is a journalist. Starting out in London in the 1960s, he covered entertainment and the exploding popular music scene. His personal life drew him into a direct relationship with dance and eventually he came to write about it. After over three decades of covering dance, music and theatre in Vancouver, he moved onto advocating the importance of the arts, all arts, in culture and education in Canada. He wrote a book about this too, The Defiant Imagination: Why Culture Matters (2004), and is working on a sequel.

Though his career focus has broadened beyond dance in recent years, Wyman remains in the know – dance, after all, is his favourite art form. As he continues his advocacy work in municipal, provincial, national and international arenas, we should consider ourselves lucky that his is a voice that can speak to dance, understands dance, loves dance. It is a new year and as we dare to have renewed hope and dreams for the future of our art form in these trying times, it is good to have someone like Wyman onside.

Enjoy the interview and happy new year!

Enjoy the interview.

Seika Boye

INTERVIEW

Name: Max Wyman

Date of birth: May 14, 1939

Place of birth: Wellingborough, in the English Midlands

SB: What was your path to becoming a dance historian?

MW: I came to Canada in 1967 with my first wife Anna Wyman. She ran her dance company, The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre, here in Vancouver for a long time. We had two children and we left London looking for new adventures and came to the west coast. Before we left I’d been working as a journalist in London and I wrote to The Vancouver Sun and said, “I’m on my way and I’m God’s gift to journalism.” I sent them a big lavish brochure about my work. They told me not to bother, that they didn’t have any vacancies and told me to go to Toronto or Winnipeg.

We arrived in Vancouver on a wet Sunday night and the following morning I went down to The Sun and said, “I’m here,” and they said, “Well aren’t you lucky, somebody’s been fired.” So, I got the job and I was with The Vancouver Sun for about thirty-five years. I did general reporting for awhile; I was new to the city, I had no claim on anything else, but I would get into discussions with the music critic who was also the dance critic and within about six months I was doing the music and dance beat.

SB: You had been doing general reporting while you were in London?

MW: Mostly music and entertainment for various magazines and newspapers. It was the sixties and I was very involved in the popular music scene.

SB: You obviously took on dance and had some comfort with it because of Anna’s work?

MW: That’s right. I think I wrote my first dance review in London when I was eighteen, but once I got together with Anna I spent a lot of time in the studio, watching her work and talking to her about her work. I learned a great deal from being around Anna. When we came here she was setting up her school and out of the school came her company. I toured with them for awhile as their general production manager before we broke up.

SB: Had you been exposed to very much dance before you met Anna?

MW: Not particularly, I’d done some reviewing, as I said, but I was never a dancer or performer. Well, I performed once, for the queen.

SB: What’s the story there?

MW: I was nine years old, it was in Nottingham where I was growing up. She came to visit – she was just the princess then. All of the kids in Nottingham were taken out into a clearing in Sherwood Forest and made to dance country dances for her. I’ve always remembered her coming down a ramp in a beautiful open car, in a big pink hat, in a beautiful pink dress … it’s engraved in my memory. I danced for the queen. It was lovely. I was really disappointed when I met her a few years ago and she had no memories of me at all!

I have to tell you too that I’m going to be on the stage again in January in a work by French choreographer Jérôme Bel.

SB: How did that come about?

MW: It’s a piece called The Show Must Go On. He mixes professional with non-professional performers. It’s a very interesting piece and has been extremely controversial in Europe because of what it does in terms of exposing people and challenging conventional notions of performer and audience. There are eighteen pieces of pop music and a DJ who gets the cast to perform in various ways. Some of it is dance, some of it is not dance. There’s a unison Macarena. It’s sounds like a lot of fun, so I volunteered to take part – it will be an interesting exchange. There are some very fine dancers involved, Noam Gagnon is part of it. I’m sort of hoping that he’ll be my study buddy. I’ve been a great admirer of Noam for a long time.

SB: You must have still been reviewing when he and Holy Body Tattoo were getting started?

MW: Yes, very much so. I was reviewing until ten or fifteen years ago.

SB: Why did you stop?

MW: I launched The Vancouver Sun‘s Review of Books in the mid-nineties and that took all of my time. It was a big job to launch a new section. The newspaper dedicated a lot of time and space to it. It was a wonderful few years. I also ran Saturday Review, the weekend magazine, which was a big job as well. I’d done a lot of reviewing by that time so I moved onto editing.

SB: What are you working on right now?

MW: I am working on a sequel to my book The Defiant Imagination, which is about the importance of arts in education, but it’s on the back burner while I work on revisions to a novel I’m writing.

SB: Tell me about it.

MW: I spent the last three years as the mayor of my community here called Lions Bay, which is just outside of Vancouver. It is a little village of about 1,500 people, on the way to Whistler. It’s in the forest, on the mountainside, beside the ocean. It’s just idyllic. I was asked to run for mayor and got in. During my time, the highway to Whistler was being upgraded from a two-lane winding road to a four-lane major highway.

The interesting thing about the job was that it got me onto the board of Metro Vancouver, which is comprised of all of the mayors in the region, and I was able to persuade Metro Vancouver that it had a major role to play in terms of culture and the environment. Last year they agreed to set up a new standing committee on cultural planning. So, I’ve become a bit of an advocate for arts and culture and have moved away from pure dance, which consumed me for so many years, into a broader area of advocacy for the arts in general and arts and education in particular.

SB: How did this experience lead to your novel?

MW: The novel is loosely based on things I learned during my tenure as mayor. It’s light, what author Graham Greene called an entertainment. You learn an awful lot about people when you do small town politics.

SB: Have you written fiction before?

MW: No I haven’t, though some people would say that my reviews were.

SB: Would you argue differently?

MW: No, actually. If I didn’t know what was going on on-stage, which is often the case when you’re watching modern dance, I would make it up. I think it’s what you’re free to do. Afterwards, choreographers would occasionally write saying, “Thanks for explaining it to me.”

SB: How does writing fiction compare to writing non-fiction?

MW: I find all writing quite wonderful. It’s what I do. It makes me tick. In fiction you’re not restrained in anyway, although I never restrained myself much as a critic either. The only restraint I had when I was writing criticism was that I didn’t use jargon. You don’t try to snow your reader with knowledge. I’m not an academic, the only degree I have is an honorary one from Simon Fraser University. I try to make history accessible, entertaining, understandable and enlightening, all in the same bundle, through the way I write.

The closest parallel, I think, is journalist Peter C. Newman, who is a friend of mine. He writes in a very accessible way and tells stories, that’s how he tells history and that’s how I’ve approached it as well.

The very beginnings of this process for me, of writing dance history, all began in the 1970s when I was asked by Dance Magazine to write a profile of The Royal Winnipeg Ballet. They used to run a big centre section of sixteen to twenty-four pages dedicated to an individual company. The RWB suggested me as someone to do it.

I wrote it as a movie – the whole piece was as if the RWB’s story was a movie complete with script and actions and all that kind of stuff. I was really quite intrigued by what I learned in Winnipeg and with the whole process and so I made a pitch to the Canada Council for funding so I could take some time off from my job to write a full-scale story of the RWB. That led to my first book, The Royal Winnipeg Ballet, The First Forty Years, in 1979.

I then went back to the paper, but I was really bitten by the dance history bug and I realized there wasn’t much around in Canada. Dance writer Michael Crabb and photographer Andrew Oxenham had done a short history of early dance in Canada in 1977, called Dance Today In Canada. That was a start, there was very little else – these days, it’s hard to think how little there was.

I then got a year off from the paper and received a Canada Council Senior Artist Grant to do research. I told people I was writing a history of dance in Canada and they would respond saying, “Well that will be a slim volume, won’t it?” But there are an awful lot of good stories and I was very fortunate in that I hit the time when all of the people who were early founders were still around. I was able to interview just about every key player. Few people had had a chance to do a lot of looking at dance across Canada. I was an assessor for the Canada Council Dance Section for a long time through the late 1960s and early 1970s and it gave me a chance to get across the country and see what was going on. I was very fortunate to have that knowledge; few people can do that because it’s such a strange country in terms of spread. It would cost a fortune to see what’s going on; we’re constantly challenged by our geography.

The year I took off I just went travelling; I took two very intensive trips across the country and interviewed everybody. I’ve still got the tapes, transcriptions and materials. In some places where I’d turn up, their so-called archives were just chaos. Out of that research, in 1989, came my dance history book. I originally wanted to call it “Snow Shoes, Toe Shoes and Bare Feet”. I guess they decided Dance In Canada: An Illustrated History, would be more proper.

That book did very well; it was the first time such a project had been done. Of course it’s been superseded since then by dance programs and all the post-graduate research. It is wonderful that so much is going on these days and everyone is covering all of the things that I didn’t get to – there are lots more stories. The basic skeleton of what happened is in that book, but there is the notion that you invent history as you write it. When you are trying to structure a story, without meaning to, you choose some things over others. I’m so happy that there is now such an interest in filling in all the gaps.

Then, I’ve been in love with Evelyn Hart ever since I was the first critic to write about her, so I did a biography of her, Evelyn Hart: An Intimate Portrait (1991) and my dance books started to grow.

Lawrence and Miriam Adams at Dance Collection Danse asked me to do a compendium of my writings about dance, and that was the beginning of Revealing Dance: Selected Writings, 1970s-2001 (2001). I was astonished at how many words there were. Lawrence and I spent a lot of time trying to work out what to put in and what to leave out.

Dance has propelled my career and my life. I would be a different person without dance. I will say to anyone who will listen – in my view, dance is the most satisfying art form because of its immediacy and its transience.

I get pierced sometimes seeing people move together on-stage, making me feel deeply emotional, or entertaining me, or making me laugh, or making me think. I believe that any art form that can do that to you and leave you a different person afterwards is worth your time. That is why I’ve spent my life looking at dance. Not to mention that it is beautiful. Who wouldn’t want to look at beautiful women and beautiful men? There’s the whole sexual thing that’s in there too and no one ever talks about it.

SB: If you could go to an era of the dance past where would you go?

I would go to St. Petersburg in the period of Marius Petipa and Pyotr IIyich Tchaikovsky. I would love to be a fly on the wall when it was all happening. Petipa saying, “I want eight measures in 4/4 please,” and Tchaikovsky would go off and write them.

They’re all buried together in the Tikhvin Cemetery in St. Petersburg. Tchaikovsky, Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, the whole Russian musical gang, and Petipa. Tchaikovsky’s grave has got angels flying over him, golden sheets of music, it’s very ornate. But all Petipa has is a very modest, classically proportioned headstone in the grass.

That time when they were working together must have been fascinating. I would love to know about the real relationship between Lev Ivanov and Petipa. Who actually did what and how? Petipa didn’t speak much Russian, and he lived there for sixty years.

SB: Who knows what was lost or gained in translation?

MW: Exactly, and we see Petipa as the father of classical ballet.

SB: Is there a particular work that you’d like to see?

MW: Oh no, any one. It would be interesting to watch him make Sleeping Beauty and see them work together on Swan Lake, or La Bayadère…. There is a little work he made called Cavalryman’s Halt, which I saw once in Kyiv…

There is also the relationship with the Tsar. He saw the first rehearsal of Sleeping Beauty, and he said, “very nice.” Very nice, oh, well, thank-you! I was once there for the opening of the season in Russia, working on my biography of Oleg Vinogradov, who ran the Kirov for a couple of decades, and I got to sit in the Tsar’s box. I realized that is the perfect viewpoint for seeing all of those ranks of swans – that’s the viewpoint they were choreographed for.

SB: Do you ever miss writing exclusively about dance and having a constant awareness of what is going on?

MW: I don’t really. I try to stay as aware as I can and I still see a lot of dance. I used to see a lot with my wife Susan who was a critic too. In fact, she took my job at The Sun. She’s been very sick for a long time and hasn’t been able to write. In my view she was the best in the country; she was really in her prime when she was stricken. We would go out together to dance performances. I wrote for The Province for a decade, which is the morning paper here, and she wrote for The Sun. We’d go to the show together, sit together and go back to the office and write our reviews, and they were very different. She was a very exigent critic – classical and rigorous. I am more romantic and easy going. It was very interesting for us to do our work in opposition, but alongside each other. We never talked about the stuff until afterwards; when we were driving home we would talk about it. It was fun to do that. It’s a shame she hasn’t been able to write for twenty-five years now, it’s one of those little tragedies that hits people. She’s very smart, she’s still my best critic.

SB: You’re lucky to have that.

MW: Yes, yes I am.

PUBLICATIONS

- The Royal Winnipeg Ballet: The First Forty Years (Doubleday, 1978)

- Dance Canada: An Illustrated History (Douglas & McIntyre, 1989) (included in

Great Canadian Books of the Century, Vancouver Public Library, 1999)

- Evelyn Hart: An Intimate Portrait (McClelland & Stewart, 1991)

- Vancouver Forum: Old Powers, New Forces (ed.) (Douglas & McIntyre, 1992)

- Toni Cavelti: A Jeweller’s Life (Douglas & McIntyre, October, 1996)

- Revealing Dance: Selected Writings, 1970s-2001 (Dance Collection Danse Press/es, 2001)

- The Defiant Imagination: Why Culture Matters (Douglas & McIntyre, March, 2004)

- Biography of Oleg Vinogradov, former artistic director of the Kirov Ballet of St. Petersburg (in final draft).

PERSONNEL

Miriam Adams, C.M.

Co-founder/Advisor

Amy Bowring

Executive and Curatorial Director

Jay Rankin

Administrative Director

Vickie Fagan

Director of Development and Producer/Hall of Fame

Elisabeth Kelly

Archives and Programming Coordinator

Michael Ripley

Marketing & Sales Coordinator

CONTACT

1303 – 2 Carlton St.

Toronto, ON

M5B 1J3

Canada

Phone: 416-365-3233

Fax: 416-365-3169

info [AT] dcd.ca

HOURS

Mon. – Fri. 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Appointment Required

Contact our team by email or call one of the numbers above